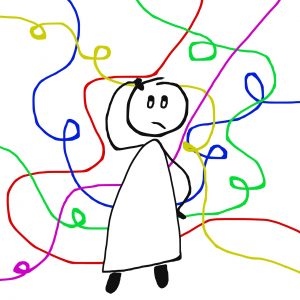

“How did I get here, I don’t know what I am doing”

As a PhD student this is a frequent thought that runs through my head, like a nagging idea that I have tricked my way to grad school. Everyone around me seems so much more knowledgeable and on top of it than I feel. The feelings always hit strongly when I am teaching or talking in front of others, I think “who am I to be sharing this expertise?”. This is not a new experience for me though, even before grad school, during my undergraduate degree, I remember also having similar feelings. Like I did not earn my way to where I was, and I was a fraud, and fell through the cracks somehow. No matter how well I do and how much I have achieved in my studies, I can never quite shake the feeling that I do not deserve to be here.

As a PhD student this is a frequent thought that runs through my head, like a nagging idea that I have tricked my way to grad school. Everyone around me seems so much more knowledgeable and on top of it than I feel. The feelings always hit strongly when I am teaching or talking in front of others, I think “who am I to be sharing this expertise?”. This is not a new experience for me though, even before grad school, during my undergraduate degree, I remember also having similar feelings. Like I did not earn my way to where I was, and I was a fraud, and fell through the cracks somehow. No matter how well I do and how much I have achieved in my studies, I can never quite shake the feeling that I do not deserve to be here.

Imposter syndrome is not currently a specific diagnosable mental illness, but is a condition recognized by psychologists and others as a genuine and particular form of self-doubt related to your own intellectual abilities. These feelings can often be come with related anxiety and depression, either due to the imposter syndrome itself or where previous anxiety and depression is exacerbated by the imposter syndrome. In a 2013 article by the American Psychological Association, William Summerville described imposter syndrome as:

“A sense of being thrown into the deep end of the pool and needing to learn to swim, but I wasn’t just questioning whether I could survive. In a fundamental way, I was asking, ‘Am I a swimmer?'”.

To me this quote precisely highlights how the self-doubt experienced by people with imposter syndrome can cause fundamental feelings of uncertainty in your chosen path in life. It is hard to keep going when you feel like you don’t belong, like you’re not good enough, are doomed to fail at your goals, and be exposed as a fraud.

However, if like me you experience these feelings you are not alone. Though estimates on the prevalence of imposter syndrome can wildly vary, a 2021 paper looking at imposter syndrome in medical students estimated the prevalence to be between 23.6% and 42.1%. So in a class of 100 students that would mean that between 23 and 42 of them have these feelings. That is 2-4 individuals experiencing imposter syndrome in every 10 of your university friends. As Karen Kelsey discusses in their 2015 book (The Professor Is In), the feelings of imposter syndrome disproportionately effect some groups in higher education communities. This is individuals with identities in communities that may feel more isolated, or that may see themselves as outside of the norm, and these groups are more likely to experience imposter syndrome. Examples of these communities may be: race, gender identity, sexuality, family background (class or education), and disability, just to highlight a few. This intersectionality in minority characteristics or underrepresented groups may have many causes, such as increased instances of policing these peoples’ behaviors and reinforcement by microaggressions, but regardless of the cause it is important to highlight some groups are more likely to be affected. Additionally, evidence is emerging that COVID-19 may be causing an increase in prevalence of imposter syndrome, with the disruption to learning and exams meaning individuals now entering university are more likely experience these feelings.

But this isn’t something we talk about. Even writing this blog post alone in a safe space has caused me to feel very vulnerable. As a society we are not used to sharing things that can be perceived as weakness. However, talking about your feelings is not weakness, and by creating open dialogues in our university communities we can remove the perceived stigma around expressing these feelings.

But this isn’t something we talk about. Even writing this blog post alone in a safe space has caused me to feel very vulnerable. As a society we are not used to sharing things that can be perceived as weakness. However, talking about your feelings is not weakness, and by creating open dialogues in our university communities we can remove the perceived stigma around expressing these feelings.

So how do we help with the feelings associated with imposter syndrome? Well, I believe the first step is to talk about it more and help others understand how common an experience imposter syndrome is. Knowing the difficulties we each face, and talking about our own self-doubts, we can help to lessen the feelings of loneliness and anxiety that can stem from imposter syndrome. These feelings try to isolate us, but by talking about our challenges together, we can form supportive communities to help each other. Another useful idea may be to start a log for when you receive positive results or feedback, as these experiences can be easily forgotten if we receive something we perceive as negative. By collecting these positive comments together, you can be more reassured about your own abilities, and look back on them whenever you need to. This 4 minute video neatly summarizes imposter syndrome and some of the ways we can combat these feelings, and may be a good resources to share with others to start a conversation:

If you are a UVic student and are struggling, remember there are a wide variety of student wellness supports you can utilize to help your mental health and these can be found here.

Let’s keep talking about mental health together <3

The views expressed in this blog are my own, and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of the University of Victoria. I monitor posts and comments to ensure all content complies with the University of Victoria Guidelines on Blogging.