(Photo Copyright: Chris Hawkins)

Interview by Teresa

From the stage to the page, Tallas Munro is a polymath of artistic endeavours. From the Fringe Festival to Phoenix theatre productions, he has become a rising star of the theatre community. The third year Fine Arts student released Death Before Life last year, a book of poetry that details his confrontation with tribulations and ultimately the cathartic process of deep introspection. Munro, of Mi’kmaq descent, details his time living on a Northern Alberta reserve in his youth in his book. Most notably, through poems such as Blurred, Little Do They Know, and A Comforting Thought he acknowledges his time there through the creative process of pen to paper. Munro’s poetics evoke George Herbert and Kafka through his “neatness”— a tension between complexity and simplicity. In my interview with the poet, I had a chance to discuss the publishing process, his inspirations for the book, and the importance of mental health:

TS: What does mental health mean to you? How does it inform your poetry?

TM: It means so much mainly because I feel especially now there is an increasing transparency in our culture. Here on the west coast, everything seems so different, so open. People seem more open to sharing their troubles or unafraid to talk about their grievances. I think that there shouldn’t be an expectation to be perfect and I think that my generation denotes more of an acceptance of oneself. I don’t know how that came about, but I think we see where our parents are and we decide that we are going to be different. The reason why I write poetry is that I want to let people that they are not alone. We read to know that we are not alone—and that’s essential. If we can connect to a piece of art that can teach us something about ourselves or our emotional state our spiritual being it can be informative our past and enlighten our potential future. I feel like if my poetry can comfort one person through my time on the reserve, or an Indigenous kid who feels like they have no way out, they can read this and say I can relate to this. And that means so much to me to be able to speak my truth and help someone in the process.

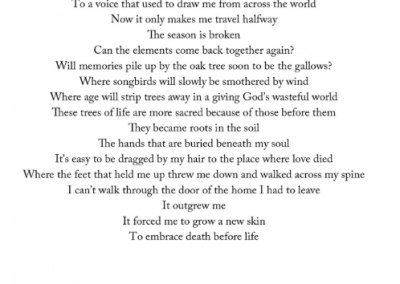

TS: Your opening poem and the title of your book is Death Before Life. The cover exemplifies its paradoxical relationship. What does this metaphor signify in terms of resilience?

TM: I see it as the opening or my thesis statement for the rest of the book. Death can mean many different things in writing. How I approached it was through different perspectives of its aftermath. The opening lines (“The sun didn’t come up this morning/The season is broken/ Can the elements come back to together again?”) signifies having a dramatic shift in disposition. In feeling a sense of complete loss over something you depended on. And when you lose something, it feels like it’s the end of your world. And through this process, you don’t know how to handle other parts of your life because your anchor that you had is now gone. So that poem is partially about that and also it is in my own way foreshadowing the development of the rest of the book. By way of this, there is now a clean slate and there can be other things that can come. But you first have to go through this process of loss. So in a secretive way, death is like a messenger of joy. Of course, death is a frightening thing, a sad thing, but in secret it can be a doorway to something better—if you just allow yourself to let go of what was holding you back and grow as a person. Overall it reflects pacing my journey and everything that I stand for. I like the idea of resilience, and having to lose something within yourself to become better. I wanted to express that in the book about how I felt on the reserve and what I had seen and gone through.

TS: Most notably, your poetry’s roots are established through your experiences living on an Indigenous reserve. What have you learned about your experience through the creative process?

TM: The reserve that I lived on had many inter-generational issues. It is a beautiful place with a lot of problems. Essentially before I moved there I had always written, mostly on scraps of paper that I could find around. I never felt I could communicate my feelings with the people surrounding me. I always felt very alone with my ideas. The writing was an outlet for me to express things that I couldn’t openly express out loud. When I lived on the reserve with my father, he was the principal of one of the local schools. It was a very tough job and consequently, I was alone a lot of the time. I didn’t feel like I was a part of the community there and through that isolation, I wrote every day. I had so many emotions inside me and it was made worse by the fact that I was physically alone a lot of the time. I also was going through things with relationships and I was a writing a lot more and realized that I was slowly making a book. Overall it was inspired by my time on this reserve but also about my relationships with people, with nature, and how I see myself and my own spirituality. I think it was a very healing thing- it was cathartic to write it and to get those emotions out. I had 180 drafts by the end of it and I found my editor, Lorraine Gane and graphic designer, Connor Hengen. I wanted it to be a collaborative process and that’s when it all really took shape was through working with them.

TS: What do you hope your readership will embody through your poetry and ultimately your truth?

TM: My father has a friend who writes books named James Heidema. He was my mentor throughout this writing process. Ultimately writing the book was a long process. I did 14 hour days during it all. The first eight were doing paid work, landscaping and hard labour and immediately I would go home, grab my laptop, and sit in Tim Hortons for six hours and do editing. I just felt as if the time was right to do it. I learned that you just can’t stop, you have to keep going. Creativity is a muscle that you need to work, it can become lax if you don’t work it out. It is essential to internalize and reflect on art and the people around you. Work with those things because they are elements that affect us the deepest in this life. I hope people embody the process of working through their issues. The opening poem took me 2-3 years to write. And through this, I found my truth. I hope my readership will embody this. All of us feel at times isolated amongst groups of people, frustrated with ourselves, and question who can we rely on. The thing that is always constant is our ability to find something positive within ourselves or circumstances that lead us on the road to healing. I hope people get a sense of my story. The last half is very much about how I’ve changed in a sense of maturation. I hope my readership resonates with my path and find their own by way of this.

TS: What does your poetry do for your sense of introspection that other modes of creativity cannot fulfill?

TM: I tried painting but that didn’t work out too well (interrupted by laughter). I see poetry as just the beginning. Poetry was the most accessible to me so I just wrote my ideas. It was my solace growing up and still is to this day.

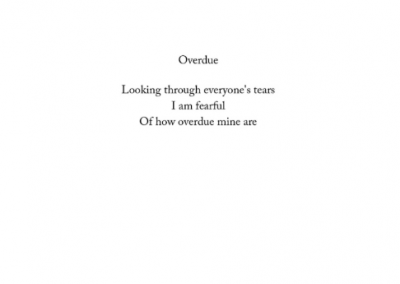

If you would like to read more about Tallas and his poetry, pick up a copy of Death Before Life at the link below. Enjoy these stunning excerpts:

https://www.amazon.ca/Death-Before-Life-Tallas-Munro-ebook/dp/B07G35XKBL

- Written by Teresa

Dear Tallas:

We are organizing the Day of the Covenant on Wed., 24 Nov, 2021 and we would like you tell a story about ‘Abdu’l-Baha, hopefully a story that is related to the Covenant. Please let us know soonest and/or whether you want to have your story trecorded. The members of the organizing committee for the Greater Fredericton Area are Jessie Millier, Merl Millier, Debbie van den Hoonaard and I.

Looking forward to hearing from you. Love, Will

I am so proud to see what has become of one of the brightest lights in my class in Grades 4&5 at Shediac Cape School. I have often thought about Tallas. I remember him writing such thoughtful pieces and being so excited when we worked on poetry. I am so proud of you, Tallas and look forward to seeing where you will go in life.

Wonderful interview with one of the brightest minds, compassionate heart and giving spirit, my son Tallas.

I’ve carried, nursed, consoled and was so blessed to raise such a wonderful soul. I am very proud of all he has and is achieving.

I’m looking forward to seeing what doors he chooses to open on this path we call “life”.