háy̓sxʷ q̓ə: Working With an Indigenous Language

Guest post by Anna Wortberg

I have to add something to the list of things to do on a long train ride that I wrote a few weeks ago: catching up on projects that you’ve been procrastinating since forever. So during one of my 36-hour rides, I finally finished my part of the Lkwungen dictionary.

In a previous post, I talked about the importance of Indigenous languages, why they are suffering at all, and what programs UVic offers to support communities.

Now, I want to talk about the local language we have in Victoria and how students at UVic can show their support: Lkwungen and LING431: Community-based Initiatives in Language Revitalization.

The Language We Worked With

Lkwungen was traditionally spoken by the Songhees Nation, whose reserve is located in Esquimalt today. Through the history of residential schools and similar attempts to assimilate First Nations (children) to the settlers’ culture, they have experienced an interruption in the natural passing on of their language.

That means parents were not able to fully pass on their language and culture to their children because it was repressed and punished in residential schools. Just as your parents’ teachings and guidance influence you, the following First Nations generations are still feeling the consequences.

However, in many Indigenous nations around the world that were/are suppressed and had to watch their language suffer, there are some motivated members claiming their language and their culture back. Many language activists fortunate enough to have recordings of and material about their traditional language have started language revitalization programs around the world. Often, these start with language classes that are offered in a community along with cultural programs to revive traditional gatherings and ceremonies.

Nevertheless, gathering all the needed material and deciding which measures are best for a community can be extremely challenging. Especially if a language community doesn’t have a lot of fluent speakers anymore. And this is where UVic comes in, to offer expert support during every step of the process.

Sometimes even students are able to get involved, for example through classes in the linguistics department, like LING431 “Community-based Initiatives in Language Revitalization,” which I took in Fall 2015. I learned a lot about language revitalization projects around the world and what makes them successful or not. But the most interesting thing was the final project: Write an outline for a community project of your choice or… support a local language revitalization initiative! I never decided that fast what my final project should be.

The Source We Worked With

In April 1968, Marjorie Mitchell handed in her master’s thesis for her degree in linguistics at UVic: a dictionary of Lkwungen, a dialect of Straits Salish. She mainly worked with and recorded Sophie Misheal, one of the few remaining fluent speakers at that time. Then she went and typed out nearly 150 pages on a typewriter while having to put in accents and stresses by hand. It is an incredible piece of work and immensely valued by her community.

However, it is only one step in the efforts of her ancestors to revive the language and offer active language programs. In all those years, not many people worked with Lkwungen so it still isn’t fully understood, which makes it hard to develop educational material, for example.

The Source We Created

A collection of 150 printed pages, sorted in Lkwungen, makes it hard for an English speaker to actually find something in there. So it was our job as students in the class to digitise the dictionary and therefore enable the creation of a digital, maybe even online, resource in the future.

But it was not just simple copying from paper to screen! In the last decades, there was work done with other Straits Salish languages which led to the development of a new orthography that also applied to Lkwungen. The new technology, in addition, simply allows us to use a greater variety of signs than a typewriter in 1968 did. So here’s an example of how we transliterated the dictionary:

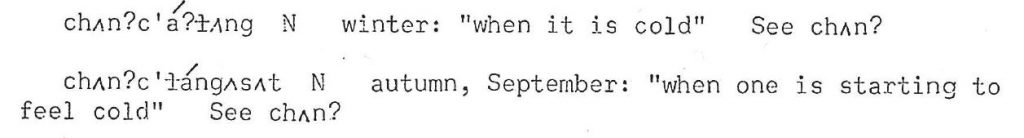

An excerpt from the original document.

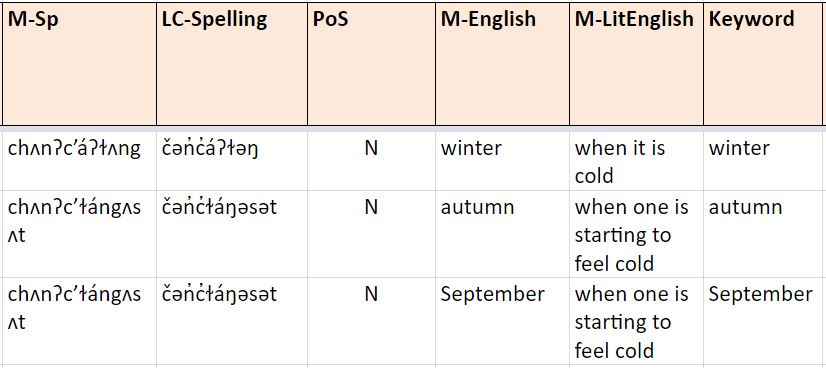

An excerpt from the digital source we created.

In the digital source, we tried to preserve as much information as possible. We still included the original but outdated spelling of words (M-Sp), the new spelling of course (LC-Spelling), the position of the subject (PoS), the translation (M-English) and the literal translation if there is one (M-LitEnglish), plus more grammatical/organizational details not pictured here. “Keyword” shows as what the entry will be listed in the finished dictionary.

It was very interesting to get to know the language through that. In this example, you can already see that Lkwungen works in a different way than English: “winter” doesn’t just mean “winter” but “when it is cold.” In Lkwungen, you can have the meaning of a whole sentence in just one word.

In English, we build up our sentences around the subject, around the active unit in the sentence, like “I,” “you” or “the dog.” Straits Salish languages, in comparison, are verb based. That means, you start with your verb and then you add things to the front and the back of it until you have everything included that you want to say.

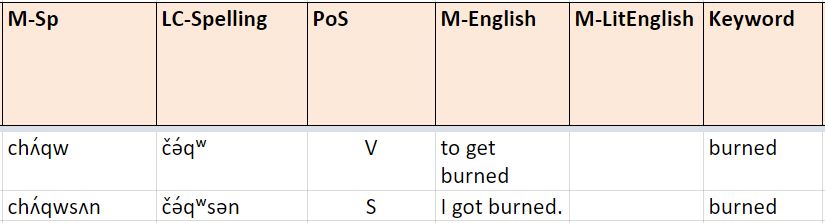

The suffix “-sən”, for example, means that I am doing something or that something is happening to me.

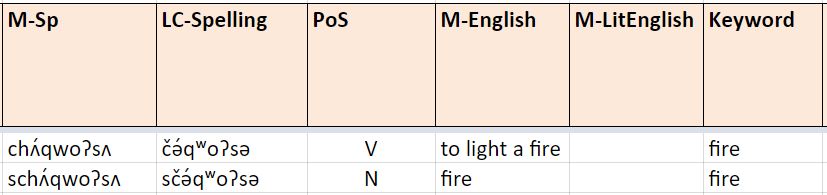

And the simple prefix “s-” can turn a verb into a noun.

The Community Using the Source

One group who’s working with the language at the moment and trying to find out more of those rules is the Lkwungen Language Class. It is a collaboration between the Songhees Nation and UVic’s linguistics department with the goal of developing material about Lkwungen and making the language more accessible.

At the moment, they’re in the process of going through all the recordings that Marjorie Mitchell made for her dictionary, learning the language themselves and trying to observe language patterns while doing so. The class is open to everyone who’s interested in getting to know the local language and being stunned by it (or maybe that’s just me being a linguistics nerd!). They meet every Monday from 6:30 to 8pm in the Songhees Wellness Centre.

I went to the class regularly during the last semester and over the summer and can only say how amazing this experience was. You’re able to listen to the original recordings of one of the last fluent speakers and learn a new appreciation of the place you live in (for example, that “Squamish” is simply the Lkwungen word for “north of Vancouver”).

For me, it was also incredible to see that a school project, like the Lkwungen dictionary, actually gets used by a group and is helpful to them. My contribution actually makes a difference for someone.

háy̓sxʷ q̓ə! (Thank you)

I found this material very interesting as I am interested myself in learning at least some Lkwungen but so far haven’t been able to find classes.

Could you let me know where classes are available.

Thank you,

Alan.

UVic offers the following:

https://www.uvic.ca/future-students/indigenous/language/index.php

Also – people can take various courses in Indigenous Language and Culture through Continuing Studies. https://continuingstudies.uvic.ca/Search?q=indigenous+language

You should contact the Program Coordinator at calr@uvic.ca or 250-721-8504 for more information. A non-student would need permission of the academic advisor of the certificate in aboriginal language revitalization program.

Is the Lkwungen dictionary available in electronic or paper format? Does the Lkwungen Language Class still meet on Monday evenings? If so, who is the contact? Thanks.

I’d contact the Songhees Nation for the answers. I was able to find some information about the language project on their website: http://songheesnation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Language_report.pdf

Ok. Thanks.

Im doing a project on first nations legends, and i need to know what the lukwengen word for wind or air movement or anything close to that definition is.