An Interview with Bill Gaston

Guest post by Kim Dias

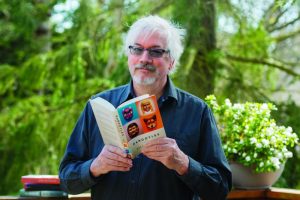

Bill Gaston has been teaching at UVic for twenty years, but I only met him in September 2018, the beginning of my third year at UVic.

Bill Gaston has been teaching at UVic for twenty years, but I only met him in September 2018, the beginning of my third year at UVic.

I’m a writing student and Bill was the professor in charge of my third-year fiction workshop. If I’m entirely honest, it really wasn’t a great semester for me, especially in terms of writing.

Everything I wrote felt bland and uninspired, and I think I spent the whole semester panicking—what if I could never find my voice? What if nothing I wrote ever felt good? I felt so awful about my own work—and on top of that, I had to submit it to one of the most prolific, well-known authors in the world of Canadian literature.

I was a bit of a mess.

After the first round of feedback I received in workshop, all I wanted to do was go home, lie face-down on my bed, and never write again. But when I finally gathered up the courage to read through Bill’s notes, they were so kind.

Firm, yes. He definitely didn’t pull punches and he didn’t sugarcoat—but sugarcoating isn’t why I’m in the writing program. His notes challenged me to do better—but more importantly, they made me believe I could do better. When I went to talk to him during office hours, I left feeling like a horrendous story could be turned to something good if I just put the work in. He made me want to put the work in.

Firm, yes. He definitely didn’t pull punches and he didn’t sugarcoat—but sugarcoating isn’t why I’m in the writing program. His notes challenged me to do better—but more importantly, they made me believe I could do better. When I went to talk to him during office hours, I left feeling like a horrendous story could be turned to something good if I just put the work in. He made me want to put the work in.

Bill retires this June and even though I haven’t known him for very long, I can’t quite imagine what the writing department will look like without him. I don’t think anyone else can, either.

We’re students and let’s be honest—we love gossiping about our professors. But Bill? Mention Bill Gaston to a group of writing majors and you’ll be met by a chorus of, “Bill? Bill’s amazing, I love Bill.” The depth of affection we have for him says more about Bill than anything I as an individual ever could. After all—you’re a kind of amazing prof if your students don’t complain about you.

Bill very kindly agreed to answer interview questions that I had for him. I’m hoping that those of you who know him can hear Bill’s wisdom and dry humour in these words, and that those of you who don’t will begin to understand just how much kindness and respect Bill Gaston bought to the UVic writing department during his years here.

Can you give us a quick overview of your career as a writer?

A hundred years ago, at UBC, when I was doing my masters degree in English Lit, I crossed the road and took as an elective a fiction-writing workshop, wrote one story, then another, and never stopped. I’d been a huge reader all my life, and in the back of my mind I had plans to try my hand at writing.

My career as a writer began gradually, as I published a story here and there, and eventually a collection, then a novel, and on it went. Forty years and almost twenty books later, it feels no different. The “career” still feels gradual. But each new story, each novel, being an entirely different beast, a new horse I have to learn how to ride, remains challenging and thrilling.

What made you go into teaching?

I don’t want to disrespect the profession and my own long career as a teacher when I say that I began teaching to pay the bills, but it’s true. I write “literary fiction,” which is maybe a fancy way of saying I don’t sell many books.

None of this is to imply that I don’t enjoy teaching, or try to do it well. My first full time teaching gig was at Seneca College, in Toronto, where I taught composition and Canadian Literature to firefighters, cosmeticians and aspiring gymnasts. Then a dozen years as a sessional instructor in the Maritimes, at four different institutions, in Halifax three at once.

Twenty years ago, UVic called, both because its writing program was the best in the country and because they considered artistic creation—my published books—as worthy, on par with more traditional academic research. So I was hired, and tenure followed, which was a huge relief, seeing as we now had four children and badly needed some stability, not to mention a dental plan.

What great good luck to end up in one of the best places in the world! And it’s been kind of wonderful that I’ve made a decent living talking about what I love, and helping others find their own skill. Basically I’m an experienced, rickety old gardener who gets to guide others who are trying to plant their own. It never gets boring because everyone’s plants are different, and sometimes wildly interesting.

I’ve spoken to so many writing students who’ve said they’re going to miss you when you retire. What’s been your favourite thing about teaching at UVic? What’s been one of the most memorable moments?

Mostly I’ll remember students. I don’t know how we end up with so many good writers—that is, I don’t know if good writers come here, or if the program makes them good, or if it’s a combination of both, which I suspect is the case.

Mostly I’ll remember students. I don’t know how we end up with so many good writers—that is, I don’t know if good writers come here, or if the program makes them good, or if it’s a combination of both, which I suspect is the case.

And let me refine this answer about my favourite thing: It’s been a privilege being allowed to meet people at the level of their imagination, fear, vulnerability, yearning, and humour. I think writing students reveal themselves in ways that academic students often don’t, or can’t. So the relationship a writing teacher can have with students can be instantly very rich.

Also… I have to ask, because no one really seems to know. When are you planning on retiring?

I am officially pulling the plug at UVic this June 30th, at midnight. Anywhere within a mile of the place you’ll hear a loud squirchy noise as dirty water swirls around the basin and goes down the drain, plus a few corks popping off too.

Looking at your bibliography, you’ve written everything—you’ve published four out of the five genres taught at UVic. Why do you mostly lean towards fiction (assuming you do)?

I write mostly fiction because that’s what I mostly read. I think this is the case with most writers—they tend to write what they read. I suspect it’s a kind of emulation.

I write mostly fiction because that’s what I mostly read. I think this is the case with most writers—they tend to write what they read. I suspect it’s a kind of emulation.

I have a saying I sometimes encourage students with: write the story you’d most want to read. As for writing in other genres? I think the reason I sometimes stray from fiction is because certain ideas demand a different voice.

Poetry can only exist as poetry, because the ideas expressed are so fine and exactly meaningful they could be nothing but themselves in that form. And non-fiction needs a different, more direct kind of honesty than fiction’s. All the genres are just different ways, different tools, for expressing our fleeting versions of what going on around us.

Which do you prefer—writing short stories or writing novels? Do your reading preferences match up with your writing preferences?

I prefer writing novels to stories, I think for the same reasons why more readers also prefer novels to stories, and that is because of the level of involvement with the characters.

I prefer writing novels to stories, I think for the same reasons why more readers also prefer novels to stories, and that is because of the level of involvement with the characters.

In a novel you spend lots of intimate time with a character, so much so that, famously, you’re often sad when it’s over. Writing a novel, you get to create and lose yourself in an entire world. But it’s also more frightening to write a novel because it’s a multi-year commitment, and one that might fail.

It might feel like a wasted few years if the novel doesn’t come together. So, writing a story, I can relax and experiment and fool around because the commitment is far less. And that sense of freedom to fool around has apparently lent my stories something extra, since the collections tend be critically more successful than the novels. But the novels still feel like best friends.

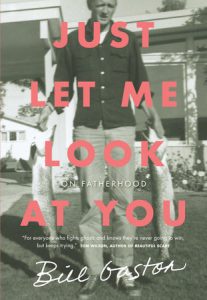

Your latest book—Just Let Me Look At You: On Fatherhood—is a memoir. It’s been 12 years since your last published creative non-fiction book. Why now?

The two memoirs are so different from each other that I don’t really consider them to be the same genre. One’s a long, mostly funny riff about something I knew well: hockey, beer, dressing-room culture, playing a kids’ game when you’re a white-haired old man, and playing it across Canada and in other countries.

The two memoirs are so different from each other that I don’t really consider them to be the same genre. One’s a long, mostly funny riff about something I knew well: hockey, beer, dressing-room culture, playing a kids’ game when you’re a white-haired old man, and playing it across Canada and in other countries.

I wrote it in a couple months, almost as a lark. Not surprisingly, it sold more than any of my other books. This recent memoir is actually a memoir, mostly about my father, and our relationship. It’s deadly serious, and it was painful but also liberating to write.

My father was a complicated person who in his childhood survived horrendous events that he told no-one about. So I’ve wanted to air his story, especially in the ways that it tied in with mine. I’d actually been writing it, and abandoning it, for about a decade. I don’t have an answer to “why now.” I suppose it had to be written while I still have the ability to remember.

You just won the City of Victoria Book Prize for the second time (for A Mariner’s Guide to Self-Sabotage). What are you proudest of in your career?

I’m proud if a book gets nominated for something, even though prizes for “art” are fairly meaningless, except as a tool for marketing. In fact the “awards season, as it’s now called,” has had a detrimental effect on Canadian literature, in that books not nominated that year are seen to have less value, and excellent books fall beneath the reading public’s radar.

I’m proud if a book gets nominated for something, even though prizes for “art” are fairly meaningless, except as a tool for marketing. In fact the “awards season, as it’s now called,” has had a detrimental effect on Canadian literature, in that books not nominated that year are seen to have less value, and excellent books fall beneath the reading public’s radar.

That said, I still love a nomination because usually the jury is made up of writers, of peers, and it’s great when other writers like your work. I suppose I’m especially proud of the Timothy Findley Award, for a body of work. But, come to think of it, the memoir has just been nominated for a Charles Taylor Award, and I’m proud of that–or maybe I’m mostly relieved to know that, at least in someone’s opinion, I told my father’s story well.

What are you going to miss the most about teaching at UVic?

People. Students, colleagues, staff. Those descriptors often fall away, and they’re more like friends.

And on the other hand… what are you most looking forward to about retirement?

No longer being bugged by all these fucking people. And I’ll finally get to start my writing career.

Anything to say to aspiring writers, specifically those in the program? Words of wisdom or inspiration? “Get out now”?

Read what you love to read, write what you love to write. It’s probably too late to get out.

Great interview, thanks. I’m a big fan of Bill Gaston.