The I-Witness Holocaust field school (GMST 489) explores the ways in which the Holocaust is memorialized in Central Europe. Learn more on the field school blog.

The I-Witness Holocaust field school (GMST 489) explores the ways in which the Holocaust is memorialized in Central Europe. Learn more on the field school blog.

Guest post by Sarah

“Millions of people around the world know what Auschwitz was but it is basic that we retain in our minds and memories awareness that it is humans who decide whether such a tragedy will ever take place again. This is the work of humans and it is humans alone who can prevent any such return.” – Professor Władysław Bartoszewski, a former Auschwitz prisoner.

In many ways, Auschwitz has become more than a former site, but rather an international symbol of the Holocaust. For this reason, it is the most visited former concentration camp, bringing in thousands of visitors each day. Because of its notoriety, there are certain expectations surrounding a visit to Auschwitz.

Expectations

We all went into this day knowing it would be difficult, but I don’t think anyone was prepared for what laid beyond the gates.

There are some things you cannot describe simply in words and pictures, but rather require the experience to fully grasp the big picture. One of these places is Auschwitz. While we’ve been preparing for this day for weeks nothing can truly prepare someone for their experience.

Like many of my peers, the majority of my knowledge of the Holocaust has come from testimonies and stories of Auschwitz. Of the four former concentration camps we’ve visited on this trip, Auschwitz was the only one I personally recognized by name. May it be the connections I’ve gained through literature or through other presentations on this trip, I felt a connection to the site upon our arrival. Unlike the days leading up to visiting other sites, I was incredibly anxious for today’s arrival.

We walked through the gates just as thousands of tourists do each day, unaware of the emotional toll that was to come. On the iron gate reads the quote “Arbeit macht frei” which translates to “work sets you free.”

1. History of Auschwitz

Auschwitz was the largest Nazi German concentration and death camp. In total Auschwitz consisted of 49 camps. Amongst these are the three main camps Auschwitz 1, 2 and 3. Auschwitz 1 and 2 are most well known as Auschwitz and Birkenau. These two sites are set 4km apart, with many prisoners commuting between camps each day.

The first camp, Auschwitz 1, opened in 1940, with the first transport of 728 Polish political prisoners arriving June 14th, 1940. The camp was known as a concentration camp, meaning labour camp. Two years later on March 1st, 1942, Auschwitz 2, Birkenau, was opened as a death camp. The function of the camp was killing prisoners through starvation and disease.

For this reason, Birkenau was set up as a site of mass murder. At the Birkenau location, there were several gas chambers and four crematoriums: Crematorium II, Crematorium III, Crematorium IV and Crematorium V. These were on a larger scale than Crematorium I, located at the main camp. While over 1.3 million victims were sent to the camps, only 400,000 were registered. The rest never made it past the train tracks and were immediately escorted to the gas chambers.

Along with the three main camps, Auschwitz consists of 46 satellite camps. Camps were set up in local neighbourhoods but stretched as far as the Czech border. These camps were all administrated by Auschwitz.

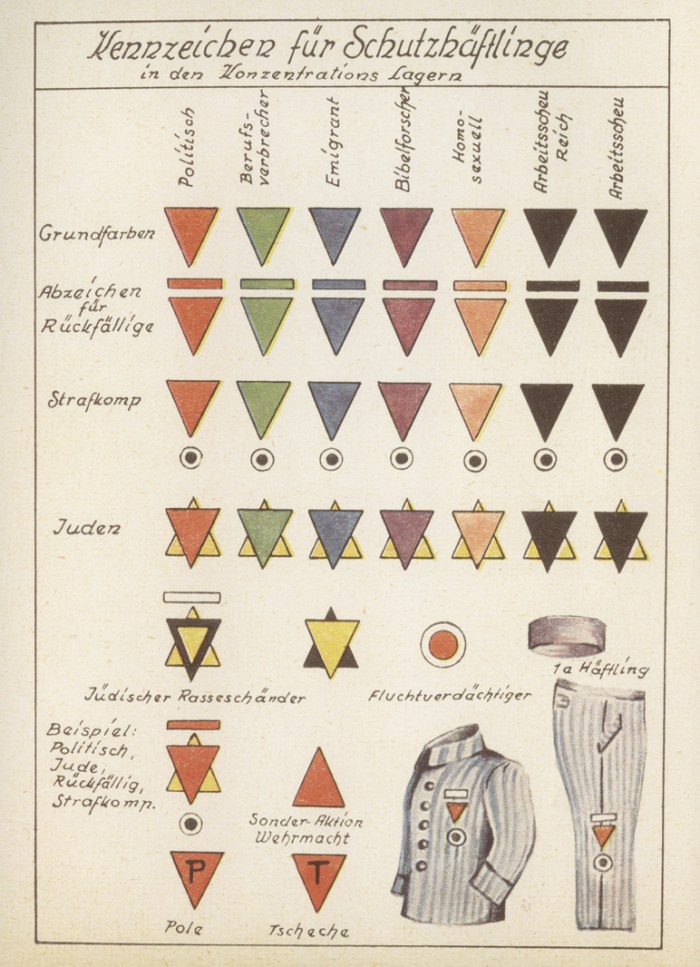

2. Leaving Life Behind

Between the years of 1940-1945, the Nazis deported over 1.3 million people to the main camp. More than half of inmates were Jews. Of the 6 million Jews who died during the Holocaust, Auschwitz accounts for over 1/6 of the deaths. Other large groups included Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and political prisoners. Prisoners were identified by a number tattooed on their arm followed by a triangle whose colour corresponded to a certain grouping.

Deportation

Transport often lasted days. One survivor from Greece recounted that his deportation lasted 11 days. These cattle cars held up to 350 passengers, sometimes stacking people on top of one another. Cars were so packed that all deportees had to stand. Parents had to hold children in their arms for fear of suffocation. After three or four days there was no longer anything to drink. Many people died on these voyages because of the lack of nutrients and the overcrowded conditions.

The arrival of Jews from Hungary in March 1944. 30,000 Hungarian Jews arrived. Approximately 75% were killed several hours after their arrival.

Depending on the condition of the transport, up to 80% of the passengers were immediately brought to the gas chambers upon arrival at the camp. These passengers included children, pregnant women and the elderly.

While visiting part of the site we heard a train off in the distance. I couldn’t help but think of the train approaching the station carrying hundreds of terrified, unknowing victims.

3. Life at Auschwitz

Living Conditions

Deportees that made it through the camp gates were issued a number and designated a barrack. These barracks typically consisted of a living quarter and sleeping room. The earlier blocks at Auschwitz 1 included minimal bathroom accommodations while later barracks at Auschwitz 2 often did not.

Each barrack consisted of triple-stacked bunk beds. Each bed held two prisoners and therefore on average, each stack held six prisoners. Barracks were made to accommodate 700 prisoners but often held over 1000. Each barrack was led by a Kappo, a prisoner of higher status – often a political prisoner, whose job was to keep civility in the barrack. Kappos were often treated with more dignity, receiving better quality clothing, safer jobs and larger quantities of food.

Barracks were poorly insulated and brought in the extreme cold during the winter. The heat was created by the body warmth of individuals. In the summer, temperatures raised high above the 30s, causing prisoners to often suffocate in the heat.

At one point we entered an old barrack. One was greeted by an overwhelming muggy room. The heat was sickeningly hot. One cannot imagine how excruciating the conditions would have been with 700 plus bodies occupying the space. In our few short minutes inside I began to feel faint. It would take an incredible amount of determination and strength to endure these conditions day after day.

Roll-Call

One of the many torments of life in the concentration camp was the daily roll-call. The entire prison population of thousands of prisoners had to stand to attention during roll-calls held in the central square.

Two roll-calls occurred each day, one in the morning starting at 4:30am and one late at night. Each lasted several hours. If prisoners were too weak to stand they would be shot on the spot. Those who arrived without proper uniform were subjected to severe beatings, often resulting in death.

If members of the barrack were missing during roll-call the rest of the barrack mates would have to stand until the missing prisoner was found. This could last for hours, in which all prisoners had to stand at full attention. The longest roll-call dated lasted approximately 20 hours.

Here photographed is the courtyard in which prisoners were lined up for daily roll-call. The sheer sight of the courtyard had me weak in the knees, struggling to keep myself from collapsing.

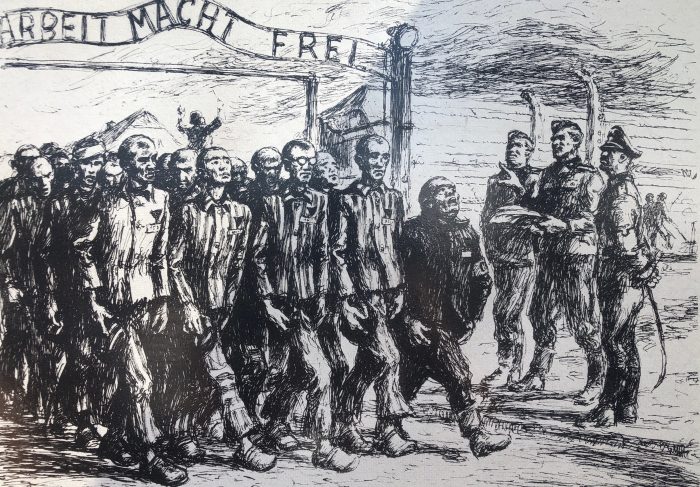

Labour

Thousands of prisoners were marched out of the camp each day for long hours of slave labour. Work days lasted from 11-14 hours in open air conditions. Prisoners were not given any protective gear and often died on site due to hazardous work conditions and extreme weather. In the evening they returned exhausted, bringing with them the corpses of those who had died throughout the day.

The drawing pictured above is a part of the “day of a prisoner” collection commissioned in 1950 by a Polish Auschwitz survivor, Mieczyslaw Kościelniak.

4. Memorializing Auschwitz

Exhibitions and Memory

One particularly difficult experience is touring the old Blocks. Many have been converted into museum spaces, exhibiting various articles and belongings of former prisoners. My mother had warned me about these exhibits, describing the piles of hair and shoes, along with other personal possessions. However, nothing could have prepared me for my reaction to seeing these items in person.

We turned the corner and saw several braids of hair displayed on an old blanket. I began to feel the colour draining from my face and a sick feeling building up in my stomach. This is what I had been warned about. But now to see it in person, my body began to shut down. Trembling I moved through the room with my head down only to reach another set of displays. This time my eyes were met with a vast mound of hair. I felt the tears in my eyes begin to well up and started to cry.

For several more exhibits, I continued to cry, the tears getting stronger and louder with every step I took. At one point I had to lean against the pain of the glass in order to keep myself from crumbling to the ground. With each room, I was met with more horrifying displays of personal possessions, the most disturbing being the shoes.

In total, the museum at Auschwitz houses over 85,000 individual shoes of victims. The uniqueness of each shoe is a reminder of the individuality of each victim lost to the Holocaust. Personally, I have a challenging time visualizing numbers and therefore was especially overwhelmed by the sheer vastness of the exhibits themselves. For the first time in my education of the Holocaust, it truly became real. These were no longer facts statistics but real people with real possessions and real lives whose stories need to be told.

5. Reflections

At one point in our tour, our guide used the well known saying: “the only way to be freed from the camp was through the crematorium.” This led me to consider my own placement in visiting this former camp.

My peers and I have had many discussions surrounding the freedom we have in visiting and moving about these sites. Unlike prisoners, we are free to move around as we please without being subjected to any forms of abuse. What might be the most significant difference is that at the end of the day we get to walk out the gates.

While our consciences may be ridden with images and personal reflection, we must always remember that visiting these sites does not make us a part of them. We can create strong connections to place and time but we nor anyone else can ever feel the experiences of these individuals.

To close, I would like to share quotes by survivors. By sharing these words I hope readers leave this blog with their own reflections and recognize the responsibility we have as citizens to remember this time and history and ensure that something of this calibre does not happen again.

“Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it” – George Santayana

“It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what we have to say.” – Primo Levi