Antibiotic Resistance: How it Works

A few days ago, I saw a sign on the side of a BC Transit bus for a program called Do Bugs Need Drugs?, which spreads awareness about antibiotic resistance and its problems. I thought I’d write about antibiotic resistance and how it works, using material I’ve learned in microbiology courses.

A few days ago, I saw a sign on the side of a BC Transit bus for a program called Do Bugs Need Drugs?, which spreads awareness about antibiotic resistance and its problems. I thought I’d write about antibiotic resistance and how it works, using material I’ve learned in microbiology courses.

How big of a problem is this? Let me put it this way, if you want to really go as something scary for a Halloween party, dress up as an antibiotic-resistant bacterium. Any microbiologist at the party will run out of the house screaming.

An introduction

With the accidental discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in the 1920s, the gateway to the world of antibiotics was opened. In World War II, it’s estimated that penicillin saved the lives of millions of wounded soldiers.

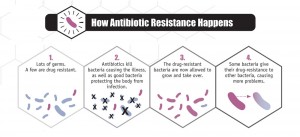

However, antibiotic resistance wasn’t predicted, because microorganisms hadn’t been studied well enough to see drug resistance. As a result, antibiotics were prescribed for many ailments including the common cold (a viral infection). Because of this over-prescription, people started developing antibiotic-resistant infections.

Today, 80% of antibiotics in the United States are used on livestock. These animals can carry resistant bacteria, which is easily spread to humans. Humans can also have resistant bacteria within them, due to overuse of antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance is described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “major threat to public health” and “no longer a prediction for the future; it is happening right now in every region of the world and has the potential to affect anyone, of any age, in any country”. This statement couldn’t be more true. If the problem persists, the WHO also predicts that we may enter a post-antibiotic era.

How microorganisms develop resistance

The underlying themes in resistance are to prevent antibiotic-binding to proteins in the bacteria or to reduce the amount of antibiotic entering the bacteria. Microorganisms achieve this by:

1. Deactivating the antibiotic by modifying it upon entry.

When an antibiotic is modified, its structure is altered. This prevents the binding of the antibiotic to its target protein.

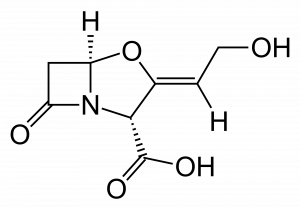

This is the most common mechanism seen in penicillin-resistant bacteria through the production of beta-lactamase enzymes. These enzymes will take penicillin and penicillin-derived drugs and break one of its chemical bonds, rendering it useless.

2. Increasing drug efflux.

This mechanism causes antibiotics to be shot out of the bacteria the moment it enters the cytoplasm. It can be accomplished by expressing protein ‘pumps’ on the bacterial surface. This prevents antibiotics from reaching their targets, and the bacteria continues to flourish.

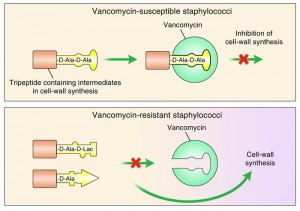

3. Altering their own proteins.

Bacteria are able to alter antibiotics, but they’re also able to alter their own molecules.

Since the main targets of antibiotics are essential proteins and ribosomes, the alteration of these targets will disrupt antibiotic binding. If the antibiotic doesn’t bind, the bacteria isn’t affected at all.

How is science fighting this?

Scientists are working to tackle antibiotic resistance. One method of addressing this issue is the production of new antibiotics.

Unfortunately, antibiotic production has slowed dramatically over the past few decades. In the 80s, three to five new antibiotics were discovered every year; today, only about one is discovered a year.

Another avenue of research is creating chemical inhibitors against the proteins responsible for conveying resistance, and combining those inhibitors with administered antibiotics. For example: clavulanic acid is able to inhibit beta-lactamase enzymes within penicillin-resistant bacteria. Without functional beta-lactamase, the bacteria becomes susceptible to penicillin once again.

It’s not just scientists who can help to combat this issue. We can also do our part. The WHO has published a list of actions that patients can take to help prevent antibiotic resistance.

So the next time you visit the doctor expecting an antibiotic prescription, understand that sometimes it’s just a virus. They’ll be doing you a favour by leaving that prescription pad in their pocket.