Opening the Unopened

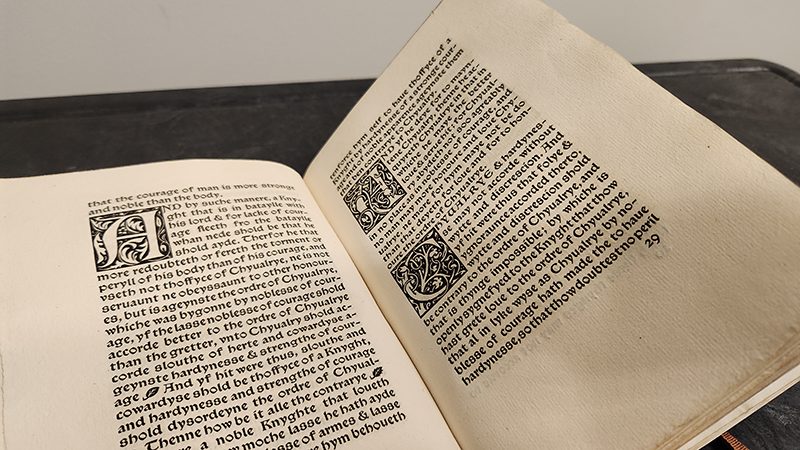

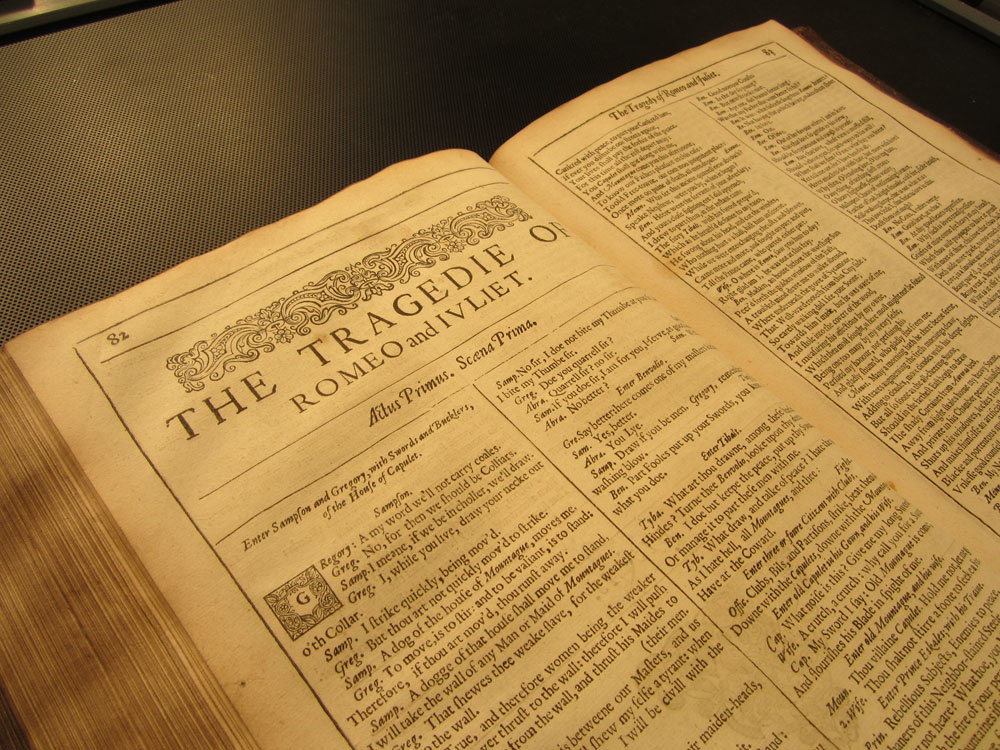

Have you ever bought a book and discovered that some of the pages are still connected to each other? Typically, this will happen along the top edge of four pages and many years ago, books were sold as such so that people knew it was a new book and not second hand.