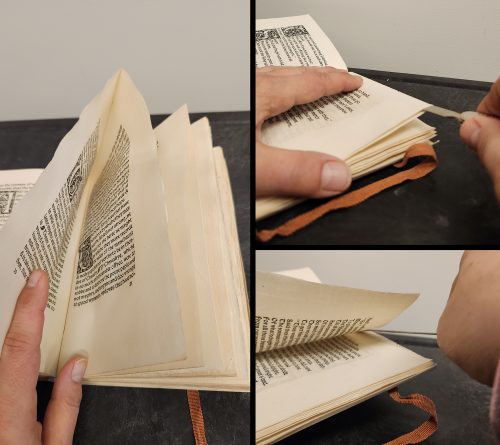

Have you ever bought a book and discovered that some of the pages are still connected to each other? Typically, this will happen along the top edge of four pages and many years ago, books were sold as such so that people knew it was a new book and not second hand. The buyer would then open them using a knife or other straight edge. These are formally called “unopened” pages though many people will mistakenly describe them as uncut, “uncut” refers to a different characteristic, where the edges of paper have not been trimmed flush by a guillotine.

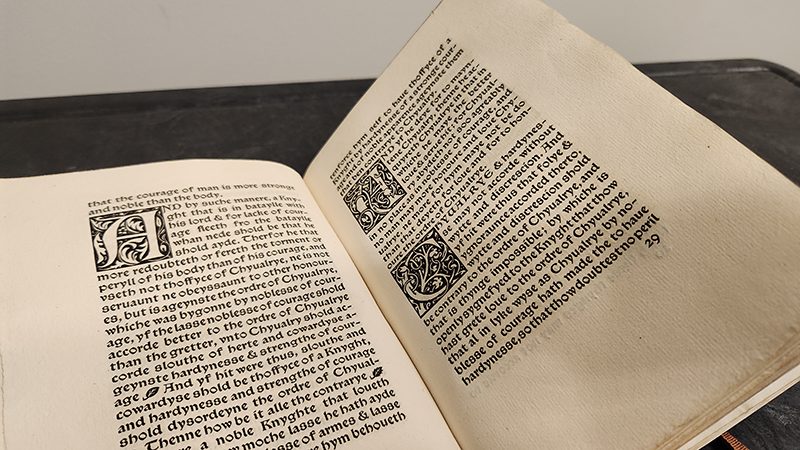

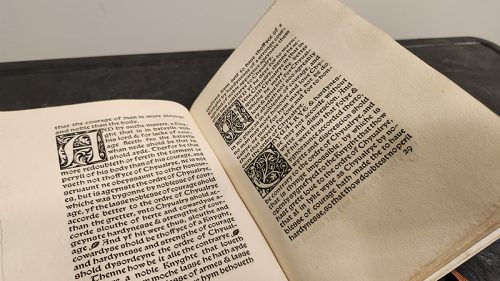

Once in a while, we come across a book, often quite old, which has unopened pages. Recently, we were scanning an 1893 limited printing of The Order of Chivalry, bound in vellum on handmade paper, and discovered a significant portion of the book was unopened pages.

In order to scan the whole book, we needed to open them. This is done by carefully supporting the pages while applying pressure to the folded paper using a letter opener, knife, or straight edge (I have used a metal ruler for less precious books!) — for this one I used a straight (rather than offset) letter opener.

Care must be taken to ensure the pages are fully separated right to the inner margin to allow the opened pages to lay flat. It can be a little scary to do this, because there is always the potential for something to go awry and for a page to be accidentally torn, but if you approach the task with a slow and steady hand, such damage can be avoided.

Instead, I see opening the unopened as exciting: our hands are the first to touch those pages; our eyes, the first to see them since they were printed.

If you’d like to see the finished scans of this book, it is part of our Book Arts Collection which “highlight[s] how books have been created and used over time, with particular emphasis on the book as a physical object.” This printing of a 15th century English translation of a 13th century French poem is a lovely example of the artistry of book making, including both red and black type, decorated initials, woodcut illustrations, and vellum binding with silk ties.

View the now opened, scanned book online https://doi.org/10.58066/z362-3039