In the course of my work, I handle old books, papers, ephemera, and so on, and often I don’t even think about it. Many of my friends outside work marvel at the books I handle that are 100 or 150 years old, but I shrug that off as many of those are in the regular circulating collection and can be borrowed as easily as the latest acquisitions. Typically friends will ask the follow up after I brush off the significance of a book from 1880 and ask, “OK, so what’s the oldest thing you’ve worked with?” The answer for that is easy: a Sumerian tablet around 4000 years old.

We were asked to digitally capture the small clay tablet from every angle so that the images could be sent to a scholar whose specialty was translating the cuneiform writing. Now our collection is that much richer as we were able to provide the translation for this object to our users without risking damage to the object through transit. We haven’t yet mounted the images online, but to get an idea, it looks a little like the clay tablet pictured here at the Dallas Public Library.

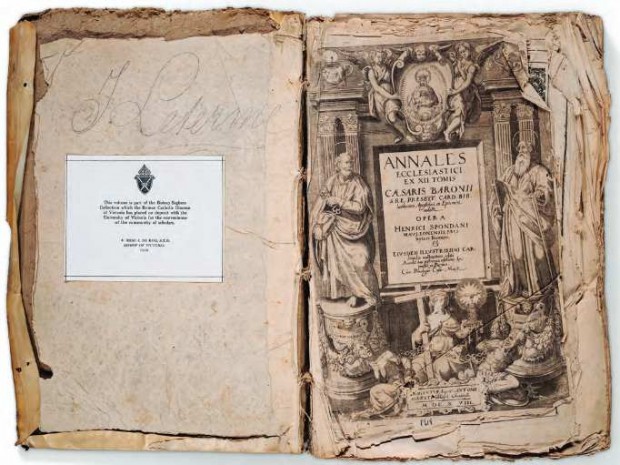

I also photographed details from a number of texts going back to the 16th century for the UVic Libraries publication, The Seghers Collection: Old Books for a New World which is available online (link is to PDF version).

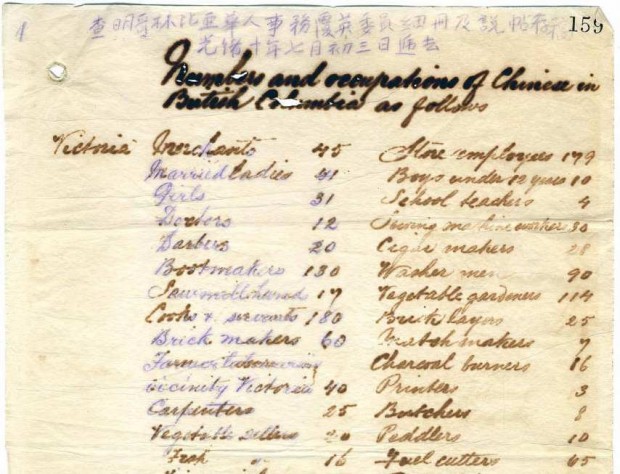

I have an undergraduate history degree and part of my focus was local history so I do tend to get more excited when I handle items that are of significance to this region. I have had the privilege to handle many items for several of our digital collections. One piece that took me by surprise was the handwritten Number and occupations of Chinese in British Columbia… from 1884, a list that amounted to an early census when Chinese residents were not otherwise counted.

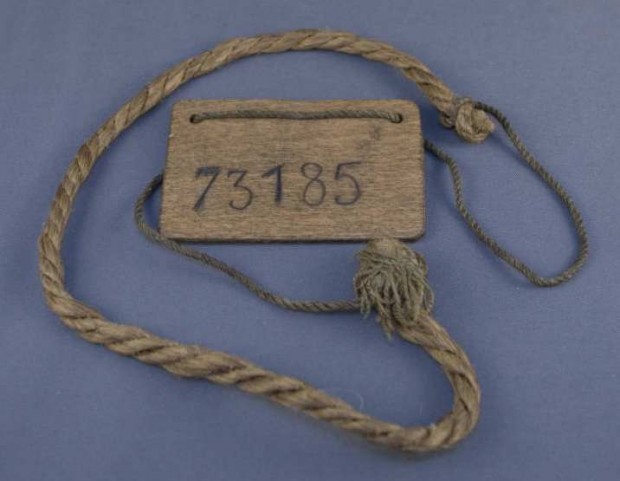

I was taken aback in quite a different way by two pieces from the Abkhazi fonds. The Abkhazi name is well known in Victoria because of the gardens they built which are now a local attraction, their house largely converted into a tea house and gift shop. However, their personal archive includes diaries and remnants of their lives during wartime, and two items that we recorded for the Curious Lives, Harmonious Gardens digital exhibit. Peggy Abkhazi had been a British civilian interned in a camp and Nicholas Abkhazi had been a prisoner of war; each had kept their identification numbers and it was very sobering to handle these artifacts.

I enjoy interacting directly with these objects from our past and sharing them with a global audience by creating digital versions. I always hope that by doing so, we not only educate those who cannot travel to Victoria but may also attract researchers or scholars who can add even more value when studying the original objects.