Lessons in Public Health

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

There is a wonderful story on PBS about how doctors are learning to treat COVID-19 patients without putting them on a ventilator. Doctor Richard Levitanor, who is an airway specialist, speaks about minimizing the use of that treatment in light of new information about how this virus behaves in the body.

Doctors can respirate patients on the “vent” for less time by providing oxygen earlier in the hospital treatment of COVID-19. Less vent equals less human resources and cost, better success and fewer deaths. Watch this video for the full interview which aired on Amanpour and Company on March 28th.

Acute Care Medicine

Photo by Jonathan Borba on Unsplash

In the clinical setting where acute medical care is happening, progress is being made by clinicians who are learning how to treat people infected with this virus. Better outcomes for patients are happening as doctors are learning how this disease progresses.

Battles are being won by patients and their clinicians, evident in those who have recovered from COVID-19. Indeed we are learning a lot, but in that learning there is grief for the loss of life.

Improving acute care medicine is always an important goal to address, and I think as a whole we are learning a lot about the capability of our society to deal with pandemic threats. In a way, COVD-19 has tested us and our ability to respond, however, responding is different than preventing. It seems that if we learn from our experience during this pandemic it will be to assess those determining factors that underlie susceptibility to illness.

The Conditions for Good Health

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

My whole life has been an exploration about healthy lifestyle, and the power we have to change health outcomes for ourselves. It is my belief that a set of circumstances is unique to any illness, and that exposure to viral agents alone does not kill people.

While the causal agent may indeed be a virus, that individual also exists in a contextual reality that either protects them from serious illness, fails to protect them, or potentially precipitates one. For example, having heart disease such as COPD can lead to pneumonia and result in complications in recovery from viral infection.

An individual might have died from an infection, but that doesn’t explain their susceptibility to disease prior to exposure. Each set of circumstances is unique where “cause of death” can be attributed to something specific to that individual and their life course.

Prevention vs. Cure

So far, we have focused primarily on the reaction to disease, and prevention gets muddled in the narrative of finding a cure, preventing transmission, or vaccination.

The way we respond to infection from a public health perspective is clear, especially as we find ourselves in the thick of an outbreak. Access to medical care is an extremely important topic right now. If we only focus on acute care, we risk missing the lessons this pandemic offers.

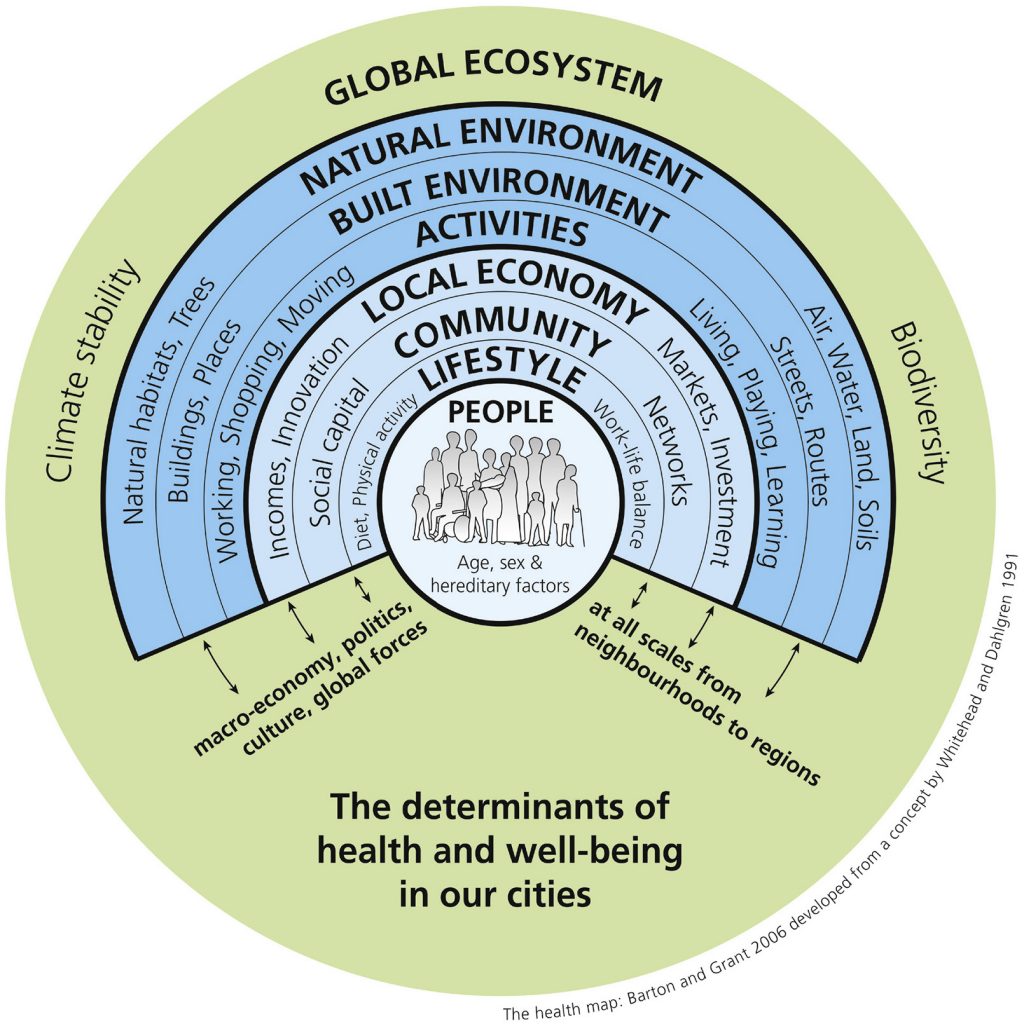

The way we prevent disease on the population level relates closely to the social determinants of health (SDOH) which underlie an individual’s set of circumstances that create vulnerability and susceptibility to the disease that is caused by infection. Resilience and protection to disease may also be achieved by improving the health of our entire population, as risk factors are addressed.

Social Determinants of Health

Barton, Hugh & Grant, Marcus. (2006). A health map for the local human habitat. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 126. 252-3. 10.1177/1466424006070466.

Interesting things are learned when we study health at the population level. People’s health relates to their socioeconomic status, the neighbourhood that they live in, the health of their home environment, and their access to food.

Education and income are important determinants. As is access to medical care and technology, clean water, and sanitation. Individual choices do factor in, which includes their health literacy. On the population level, an individual’s choices are contextualized by these determining factors.

Addressing Vulnerability

Photo by Free To Use Sounds on Unsplash

Responding to a pandemic looks different than preparing for one. If in preparation we address the Social Determinants of Health, once again we would find less vulnerable people exist in a society that is more or less equal – at lest that is intuitively so.

Health Canada describes Health Equity in the context of the Social Determinants to be: “the absence of unfair systems and policies that cause health inequalities. Health equity seeks to reduce inequalities and to increase access to opportunities and conditions conducive to health for all.” (1) We must also consider the impact of the SDOH on our population when we consider preparing for future outbreaks.

How We Protect People

Studying who has become more impacted during this pandemic will give us an understanding of how those underlying factors shape health outcomes. At the very least we can learn something about the way our society is set up to protect people, or fail to do so.

So much is already known. We have countless past experiences that have helped shape the development of public health. Practices such as hygiene, sanitation, food safety, and infectious disease control have developed because as a humanity we have faced challenges like the one we are faced with today.

What will the future tell about us? What lessons will we learn that will shape how we consider public health in our social planning? Will we learn the vital lessons needed to prevent this tragic loss of life in the future? We owe it to ourselves to build on the knowledge we have in this new scenario, and apply it to social planning, the promotion of health, and the prevention of chronic disease.

- Government of Canada (2020). Social Determinants of Health (website). Health Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html