Reflections on the I-witness Holocaust Field School

Guest post by Makayla Scharf

“So, how was your trip?” Almost three weeks since returning, this question still makes me pause.

“So, how was your trip?” Almost three weeks since returning, this question still makes me pause.

Maybe I pause because summer days have a lethargic, stretching quality; have I gone somewhere? For a split second, my mind scrambles for answers. More than this summer daze, however, I suppose I pause because my “trip,” the I-witness Holocaust Field School, did not end for me at the Kraków airport.

I packed this experience home with me, carried in my mind today as dutifully as I carried my passport through Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, and Kraków. Perhaps I will feel differently once I have handed in my final assignments, received my new class schedule, and buckled down on life as a UVic third-year. Yet, for the time being the field school has functioned for me like a rock tossed into my perceptual pond: I am still in the ripples’ grip.

The first question given to us was a short one: what is the Holocaust? The history major in me perked up. I know that, I thought. The systematic destruction of Jewish communities across Europe, ending with WWII. Yet, we learned the Jewish community has a different term for this: the Shoah. Other communities, like the Sinti and Roma, the disabled, the “asocial,” and political opponents, were also taken to concentration camps – where do these groups fit in our narrative?

When we think of the Holocaust, even the when is complicated. Did the Holocaust begin with the first deportation from Berlin, on October 18, 1941? Or with the Nuremburg Laws’ implementation on September 15, 1935? Our field school’s purpose was to analyze Holocaust memorialization, but we couldn’t even confidently pin down the event’s beginning. It dawned on me that perhaps we were in for an experience we were less equipped to handle than I had thought.

This realization came only from the first day. We hadn’t left UVic yet. Most of us were still making harried travel plans, dragging out luggage from our closets, assuring our families we would be safe. For the rest of that preparatory week, we received a crash course in Holocaust history, the modern political realities of the countries we were visiting, memorialization theory, and, when our technology rebelled during a presentation, IT trouble-shooting.

In between and during these lessons, I was introduced to the breadth of our backgrounds. Captaining our cohort was Dr. Helga Thorson, Chair of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies, and our facilitator, Andrea Van Noord. I cannot express my gratitude enough to these women, who put in a supreme amount of work both in Canada and Europe to ensure our group of seventeen students received a truly transformative experience.

How is an experience transformative? This question was a recurring theme on the trip. “Life-changing” is an intimidating concept. In the European heat, breathing in experience as easily as air, standing in sites of inconceivable pain and resistance and complex history, the answer was not obvious. You are tangled in questions.

My most dominating question was: why am I here? I came into this experience thinking I would learn more about global and interpersonal relationships, to hopefully better prepare myself for, one day, a career in international law. Looking over my statement of purpose while preparing to write this blog, I couldn’t help but laugh at my naiveté.

On this field school, I learned about hate and cruelty. At Mauthausen Memorial Centre, we heard stories of vicious kappos, of an inmate who stole another’s hat when his went missing, condemning that man to die while he lived, of the pool for the SS Officers and the football field they played on while people died not twenty paces away. But we also learned about incredible compassion. We were given stories of a kappo who snuck bread to the prisoners under his charge at this risk of his own life; of two prisoners who held up the man between them when his legs refused to hold him during one of the hours-long roll calls, saving his life.

A close up of two of the four parts of Vienna, Austria’s Monument Against War and Fascism, The Gates of Violence:

I learned about the complexity of memorials, exemplified perhaps best by the quandary of Auschwitz. Does the Jewish community have the most right to the site, or does that intrude on others who suffered there? Should the land be internationally managed somehow? What would that mean for Polish sovereignty? Auschwitz is Poland’s largest tourist attraction – what does that mean economically, historically, morally?

Moving even deeper, some question if Auschwitz should even be preserved, or be used such as it is: outfitted with gift shops, cafes, mandatory tours, car parks, and snack trucks. Watching an obviously vacationing couple take a grinning selfie by the memorial site sign, you cannot help but wonder.

Reflecting on this experience, I struggle to parse the lesson I want to impart with you most. It feels damning that I cannot find one moment that rises above the others, but every time I decide, another instances that was just as impactful occurs to me.

I think of empathy. We explored horrifying events on this field school. We all experienced moments of turmoil. Walking through the now-empty prisoner barracks of AuschwitzBirkenau, gestures of quiet support were abundant: tissues shared without question, comforting hands brushed shoulders, unobtrusive and silent, but utterly empathetic.

We stayed up at night when others couldn’t sleep. When someone fell ill, we took pictures for them so they wouldn’t miss the day. We helped each other navigate airports, train terminals, bus routes, and city streets. There was conflict– how could there not be? –but for seventeen students confined to close quarters for three weeks of intensely challenging travel and study, in my opinion, we held ourselves– and each other –together admirably.

I hope this lesson, one that was maintained sometimes with great struggle and other times without thought, is one that I will always remember to carry with me.

Tarnow, Poland – the central bimah of the town’s main synagogue before the Nazis destroyed it, now preserved in a park covering the grounds of the synagogue

I also think of academia, and how learning took on a new definition. Our cohort had History majors, with focuses spanning the globe: Russia to the Middle East to Canada’s First Nations peoples to Holocaust Studies graduate students. Art History, Public History, English, Environmental Studies, and Germanic and Slavic studies students rounded our ranks.

Specialties ranged even further, including Greek and Roman studies, theatre, law, politics, philosophy, photography, languages, and a dozen other others. Despite our exhaustion, ever-increasing as the weeks rolled on, our diverse backgrounds brought diverse points of view we would have never encountered had we remained within our departments.

Debate was always respectful, but passionate in a way I had never seen in a class room. A point would be made and six or seven hands would fly up in rebuttal or agreement. We built intricate ideas by bouncing observations off each: I thought, this is what academia should be.

Finally, when thinking of the lessons the field school gave me, I think about narrative. Coming from an English/History background, narrative is a familiar term to me. Narrative is the story that is being told. One event may have many narratives, all in conflict with each other.

On the field school, narrative came alive before my eyes. Our collective narratives about the past shape how we interact with the world, nations, strangers, and friends. In Budapest, the Orbán government offered one memorialization of Hungary’s role in the Second World War:

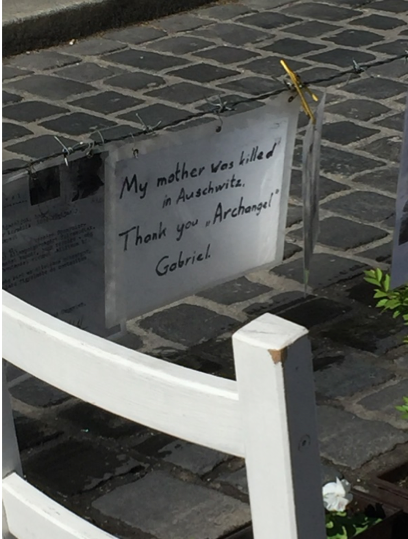

The angel Gabriel embodies Hungary, while the attacking imperial eagle represents the tyranny of the Nazis. Meant to represent the regime’s victims in Hungary collectively, the memorial is highly controversial. Many in Budapest, and Hungary at large, accuse the memorial as being revisionist; angled at eliminating Hungarian complicity in WWII. This criticism takes physical form at the foot of the statue in a counter-memorial that has stood since 2015:

Here, opposing narratives are given a materiality that, I think, can be lost when we think of narrative in academic circles. Narratives are not just battling stories told by journalists, historians, and governments. Nor are narratives simply to be agreed with or discarded casually. Often, as with this example, they are social battlefields. They are someone’s experience, their reality. The field school brought this term out of the hypothetic realm and into reality for me.

As I come to the end of this blog post, possibly this is the most enduring lesson the field school has given me: the countless hours students spend in hypothetic space, questioning and analyzing, has material impact. The challenge is bridging that gap.

This field school, that has taught me so many lessons of diversity, empathy, and experimental realities, feels in my perception like the first stone tossed down to build that bridge from.