By Marta Bashovski

It’s the end of April, the end of another academic year, and the beginning of another summer. This can be a tricky time for “senior” PhD students like me. On the one hand, my usual sources of funding and the duties that take up most of my time – teaching, TAing, and tutoring at the CAC – are on hold until the fall. On the other hand, we’re now in the midst of “conference season,” and since defending my dissertation proposal, committing to writing conference papers has been how I’ve found time to write the chapters of my dissertation. The “perks” of attending conferences – travelling to interesting places, catching up with old friends, and seeing new work in my discipline – are not bad either!

What I hope to offer in this post isn’t suggestions for how to approach conference abstracts, networking, papers, or presentations. There are many excellent guides already out there. See here, here, and here, for instance. Instead, I would like to share some reflections on the dissertation writing benefits I’ve found to regularly attending conferences.

Writing to a clear deadline

I need deadlines to be productive. The daily life an ABD PhD student with non-writing duties and commitments often means that writing gets pushed to the bottom of my to-do list. The long-term, amorphous deadlines of a dissertation project also mean that, for better or for worse (usually worse), writing happens very slowly and in tiny chunks. This is where I’ve been able to make strategic use of conference deadlines. Since the conferences I attend have application deadlines six months to a year in advance, I am able to plan when I’ll be forced, by the stress of necessity, to draft a concise version of a dissertation chapter that I can later develop further. The commitment to submit a paper draft and the accountability to a group of colleagues has helped me to prioritize scheduling – and following through on – writing time.

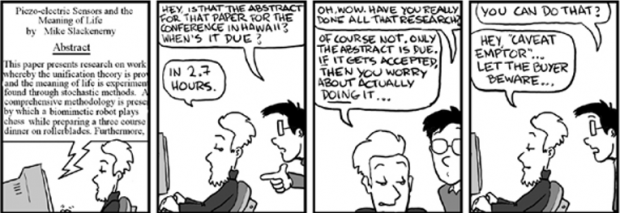

www.phdcomics.com

Clarifying the project

If your dissertation proposal was anything like mine, you quickly found that your aims were far too broad to make for manageable dissertation chapters. Taking your chapter outlines – and your ambitious plans to cover all of the relevant literature for the questions you address – and making them into conference papers is an excellent way to focus your argument to emphasize only the most important themes. I’ve found that for a typical conference paper, I write about a third to half of what I had originally planned to cover in a given dissertation chapter – and this is fine! I have the opportunity to complete a skeleton draft and can always supplement and revise this later. I have found that my original ambitious plan did not serve the purpose that I hoped to achieve in the chapter. (This post offers some more specific suggestions on writing a conference paper in a limited time – in a mere two days!)

Writing for an audience

As writers generally, and PhD students in particular, we are often told to consider who our readers will be when we write. As with elusive dissertation deadlines, though, our audiences can also be vaguely defined (our committees? other scholars in our field?). Writing for a conference comes with a built-in audience –even if that audience ends up being not many more people than your discussant and fellow panel members. Writing for a particular conference and panel, you now have a sense of the themes expected of your paper, the concepts you will need to explain, and the debates to which you hope your work will contribute. I have also found that writing for a specific, tangible audience also helps me to personify my usually densely theoretical work – it helps me to cut the jargon and focus on the takeaway I’d like the audience to remember from my talk.

Feedback and revisions

As we complete our highly specialized dissertation projects, most of the feedback we receive as we go along comes from readers who know us and our projects well – supervisors, committee members, and if we’re lucky a few friends or department colleagues. These people are mostly “insiders”: they have a sense of the orientation of our projects, our goals, and the conceptual vocabularies that frame our writing. I have found it very helpful to receive feedback from people who are interested in my project – and may be experts in the field – but do not necessarily begin from the same assumptions (and, relatedly, institutional background) as I am. Feedback from outside our own “bubbles” can offer new perspectives, new reading suggestions, or even reframe major aspects of the dissertation. The latter happened to me when a particularly conscientious discussant asked whether I would pursue a particular concept later in my dissertation – I hadn’t planned on it, but now this discussion forms the last chapter of my dissertation.

Possible caveats

Directing your dissertation writing through conference papers – and conference attendance in general – comes with several caveats, of course. First, you might find that the feedback you receive on your work is sparse or not at all helpful. Second, you might find yourself writing papers or participating on roundtables not related to your dissertation work at all. This could be a downside or not. Working on other projects might seem like a waste of time, but it might also be a welcome distraction from dissertation burnout, and an opportunity to develop new ideas for future projects and meet a new network of scholars.

I have two more conferences this summer – the British International Studies Association annual meeting in Brighton, UK and the Gregynog Ideas Lab in Newtown, Wales. At both, I’ll be presenting parts of the last chapter of my dissertation – yet to be written! In Brighton, I’m excited to be on a panel that both fits my research well and includes scholars I am eager to talk to further. In Wales, I’m looking forward to reconnecting with old friends and both sharing my own research and getting inspired by their research. In the meantime, I’ll be taking part in another long-honoured academic writing tradition – the writing retreat, in my case my brother’s sunny apartment in Sofia, Bulgaria. Have a wonderful summer and happy writing!

Marta B ashovski is a tutor at the CAC and a PhD Candidate in Political Science and Cultural, Social and Political Thought at UVic. She is most enthusiastic about food, travelling, and her cat.

ashovski is a tutor at the CAC and a PhD Candidate in Political Science and Cultural, Social and Political Thought at UVic. She is most enthusiastic about food, travelling, and her cat.