By Nancy Ami

I’d written the following sentence:

Manager-trainees need to demonstrate fundamentals of active listening

I received the following suggestion:

Manager-trainees need to demonstrate fundamentals of active listening.

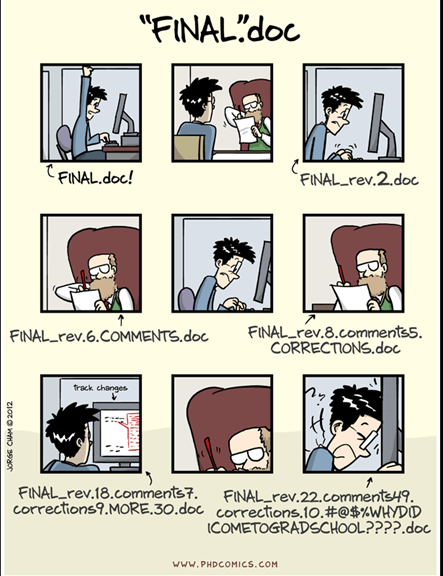

I bristled. My sentence captured my key point: given the range of active listening competencies, managers-in-training need only display fundamental active listening skills. Then I thought, “Who cares? Why am I reacting so intensely to this suggestion?”

Writers can’t help it. They are frequently elated or levelled by suggestions on their writing. In his article, ”‘I feel disappointed”: EFL university students’ emotional responses towards teacher written feedback,” Omer Mahfoodh examines university EFL students’ emotional reactions to writing feedback. He notes the range in emotions students experience when receiving feedback on their writing and suggests having such emotional responses can affect students’ understanding and utilization of teacher written feedback.

Much has been written about giving meaningful, inspiring feedback on student writing. In her book, Feedback that Moves Writers Forward: How to Escape Correcting Mode to Transform Student Writing, Patty McGee states that the biggest learning is “feedback is first about listening.” She stresses the importance of hearing writers’ intents and outlines the importance of “fundamentals” that include the phrasing and timing of written feedback. Writing coaches applying such feedback basics can inspire rather than deflate writers.

Truthfully, though, most engaged in providing writing feedback cannot pause to consider the recipients’ feelings. Typically, given the scope of the writing issues and time constraints, those burdened with assessing writing have to get the job done. Teary-eyed writers have to suck it up.

So how do writers deal with prickly feedback that misunderstands or ignores their intent? In his blogpost, ‘‘3 things every writer needs to know about editing’ Jeff Elkins recommends writers distance themselves from feedback. Editors critique writing, not writers. Most importantly, he suggests that analyzing writing feedback can give writers the most precious of gifts: insights about readers.

When we write, we imagine our audience.

We include details we think they need. We select words we think will impress. We structure arguments to convince. When a reader offers feedback that is authentic and meaningful for him, we have an opportunity to see what he sees. To practice getting inside his head. To see what’s important to him. Through analyzing readers’ comments, we have a whole new understanding of our audience, and this can inform and extend our writing. And, even better, we can use the feedback as real or imaginary conversation starters, which can teach us even more:

“I noticed that you eliminated the phrase, ‘fundamentals of’ from my sentence, Manager-trainees need to demonstrate fundamentals of active listening. I’m guessing you thought the phrase made the sentence ‘wordy,’ am I right?”

“Well, partially, but I also felt that the phrase was off-base. After all, active listening is just active listening. It’s not really that complicated, is it? Are there really ‘fundaments’ of active listening?”

“Interesting. Actually, active listening is quite complex. It involves several steps: listening intently, paraphrasing what you hear, asking for clarification, confirming intent, … blah… blah… bah…”

“No kidding! I had no idea!”

“Would it have helped if I had defined active listening in the first place?”

“Ah, yeah! Duh!”

Irritating writing feedback can stimulate reader-writer dialogue, leading to happier writers and audience-informed writing!

References

Elkins, J. 3 things every writer needs to know about editors. Retrieved from https://thewritepractice.com/receiving-feedback/?hvid=3xU5bB

Mahfoodh, O. (2017). “I feel disappointed”: EFL university students’ emotional responses towards teacher written feedback. Assessing Writing, 31. 53-72, retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2016.07.001

McGee, P. https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/16737617.Patty_McGee

Image Source: https://pixabay.com/en/despair-alone-being-alone-archetype-513529/

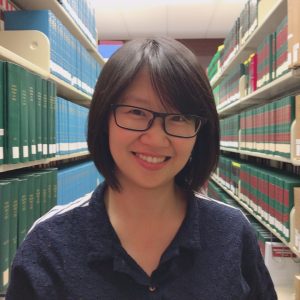

Nancy Ami is the Manager of the Centre for Academic Communication. She used to work at  the University of Lethbridge, where she taught academic writing to international students applying to undergrad programs. She also taught composition classes to undergrads applying for the faculties of management and education. Recently, at a private English language school in Victoria, Nancy helped international students with IELTS preparation, University of Cambridge FCE and CAE preparation, and academic writing.

the University of Lethbridge, where she taught academic writing to international students applying to undergrad programs. She also taught composition classes to undergrads applying for the faculties of management and education. Recently, at a private English language school in Victoria, Nancy helped international students with IELTS preparation, University of Cambridge FCE and CAE preparation, and academic writing.