By Madeline Walker with Lisa Mitchell

Last week, I wandered over to Cornett to visit Dr. Lisa Mitchell, Associate Professor and Graduate Student Adviser in the Department of Anthropology. We sat together in her cozy office on a cool March afternoon to talk about writing—a favourite topic for both of us.

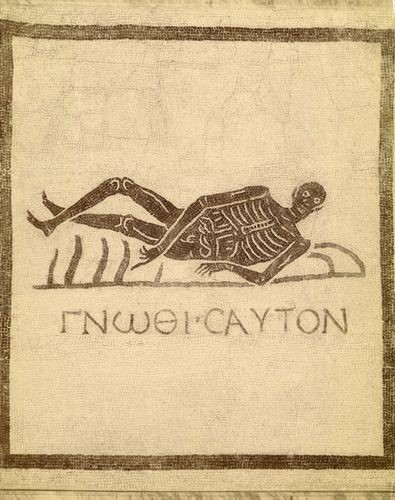

I asked Lisa about her own graduate school experience—could she share any tips gleaned from writing her dissertation? Lisa admitted that she didn’t become as “deeply reflective about how to write and especially what to do if writing doesn’t go smoothly” until she had her own graduate students. We agreed that we often learn best by teaching. Lisa’s experience supervising graduate students exposed her both to students who experienced writing as pleasurable and to students who experienced writing as terrifying, and this helped her to a realization. “I needed to get more reflective about my own writing practice and what I might offer to them to work through problems or how to take the writing to a deeper level.” Here Lisa touched on a theme she returned to several times during our dialogue: self-reflection in writing. As we become aware of our writing process, we come to know and accept ourselves as writers, and therefore we become more effective at writing, making the most of our idiosyncratic methods.

Garnered from both her own writing experience and her experience supervising, Lisa shared some of the ways she guides graduate students when they run into writing trouble. “Don’t assume that writing is easy and don’t assume it’s something natural. Take it as an aspect of your learning process. It’s a skill and needs to be practiced. Do it regularly so it becomes a habit and something you think about through that regular engagement.”

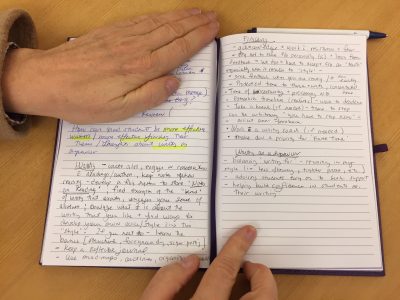

Lisa noted that in anthropology, writing is sometimes the site or space for analysis, and students may get stuck in their writing because they are “still in the process of figuring out the analysis and trying to sort it out.” She went on to describe several ways to overcome barriers that arise when we try to think things through before writing them down. “When I start a piece, it’s not unusual for me to have a very hazy, broad idea of what I’m talking about, but when I put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, I am working out the analysis as much as I am working out the narrative structure.” Lisa paused thoughtfully. “When things don’t go well, when you start to stumble in writing, change it up a little bit. Pick a different topic for even a few minutes or a day or two. If you’ve been sitting with your computer, stop and try pen and paper. In some of my classes, I have a session where you get a sentence fragment to start and you have to keep writing for five minutes. Just do freewriting. Unleash the initial apprehension about starting a writing session.”

Lisa also finds that using visual tools can help shift stuck writing. “I rely very heavily on making diagrams with my students when working through not just writing but analysis. I need to move between the word, the mind map, and the flow chart, and sometimes it is enormously helpful to sit and talk about what you are trying to write and try to represent it visually. So you have both a sense of the component elements of your writing, but also there is something very freeing, very stimulating in moving away from the word and putting it into circles and arrows.”

Another method Lisa uses when she needs to change things up is voice. “I turn on a recorder and just start talking. Sometimes it’s just me and my dogs and I’m going to start somewhere, sometimes in the middle or sometimes I think this is where I want this paper to end up. It’s a bit time consuming because you have to go back and see if there’s anything you really wanted and at times there is and at times there isn’t, but generally that process begins to bring to the surface bits and pieces that I know need to be in the piece I’m working on.”

Lisa then stressed the importance of sharing your writing: “We end up writing in little closed off spaces and there is much value in thinking about how you can make the writing more social. Talk to other people about writing – don’t assume that other people are writing without problems, without crisis. Sometimes, talking to other people about what you are writing is a way to express it differently.”

This led Lisa to think about how she shares her own work with colleagues: “I think particularly among faculty we are unwilling to share our unfinished, our unpolished drafty drafts, and I think there is enormous value in working through even some of the basic foundational elements of an argument or the structure of a piece by being willing to open yourself up a bit.” She elaborated on the metaphor of writing as conversation, a metaphor that can liberate us from the intimidating prospect of writing a thesis or dissertation: “Think of writing as a creative process. If you load it up by saying ‘I have to write my dissertation,’ that’s such a daunting process, whereas if you say ‘I want to ask some interesting questions’ and ‘I want to engage in some conversations,’ it’s so much more doable, and it also feels like something that is much more like our everyday lives. Although there are certain requirements for a dissertation or a thesis in the level of academic language, and you are engaging sources in a way you wouldn’t ordinarily in everyday conversation, by metaphorically framing what you’re doing as engaging in a conversation and asking interesting questions, you don’t take on that huge burden: ‘Now I must create original knowledge’ in five or seven chapters or whatever.”

I agreed that the conversation metaphor is very useful in academic writing, mentioning a helpful writing text based on the idea of dialogue, They Say/ I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing by Graff and Birkenstein (2010).

As the clock crept closer to the end of our allotted time, I asked Lisa for any further thoughts on how she writes best, and she reiterated the importance of opening up about your writing: “I sometimes think the reason we don’t talk about what we’re writing is there’s always a risk that we won’t finish it, so we don’t talk about it.” “Yes,” I said, “like telling people you’re quitting smoking then starting again.” Lisa laughed. “The list of things we would like to write is always longer than the list of what we actually manage to write, but I don’t think there’s any real shame in that. Sometimes part of the creative process is working through the possibilities and then settling on the one or the two that you’re ready to actually write. I tend to think of myself as a non-linear writer, so I really am one of those people that sometimes just starts in the middle. I kind of know where I should end up, but I’m not too sure where I’m starting from. I think by this point in my career I’ve made peace with that process; I don’t stress about it very much anymore and I’ve also made peace with the fact that sometimes I start articles or writing pieces that don’t get finished. Sometimes I lose interest, and other times I can’t figure out a way to tell the story that is compelling to others. It may be something I found deeply interesting, but I think why would other people care about this?”

I responded: “What I am taking away from what you have said, Lisa, is that self-reflection, self-knowledge about being a writer is extremely important. Once we know what kind of writer we are, we can make peace with that, work with it, instead of thinking we ought to be a certain way.” Lisa nodded in agreement. I left feeling validated—I am one of those “start in the messy middle” writers, and I was happy to know that others worked productively, even confidently, in this manner. Thank you, Lisa, for sharing these ideas. There’s no shame in being the writer you know you are. . . in fact, it’s cause for celebration. Writer, know thyself.

Lisa M. Mitchell is Associate Professor and Graduate Advisor in Anthropology at UVic. Her research interests are at the intersection of bodies, technology, and inequalities. She has conducted research on prenatal testing, perinatal loss and reproductive politics in Canada, on the visualizing technologies of medicine, especially ultrasound fetal imaging, on experiences and meanings of body and risk among impoverished children and their families in the Philippines and among street youth in Canada, and on bereaved parents’ use of social media.