By Madeline Walker

The word abstract is a bit confusing. When I looked up this word in the dictionary, I found the first definition is for the adjective, to do with “thought rather than matter, or in theory rather than practice; not tangible or concrete.” Thus an abstract concept, such as love, good, or evil, has no physical referent. The noun definition is “a summary of or statement of the contents of a book.” When you write an abstract for an article, thesis, or conference, you are “abstracting” (a rarely used verb form of the word, meaning to extract or pull out) some key bits from the whole. Yet contrary to the adjectival meaning of the word (non-concrete), it’s a good idea not to be too “abstract” when writing your abstract! An abstract abstract is likely to be ineffective because your goal is to deliver a clear picture of your research in your reader’s mind, and abstract language won’t do that. When you have only a few words to say a great deal, you had better be as concrete as possible in order to deliver your purpose to the reader directly.

I am a big fan of Thomson and Kamler’s four-move abstract described in Detox Your Writing: Strategies for Doctoral Researchers (available as an e-book in our library). Their model works well for all types of abstracts, and it can also be used to kick-start your writing. Thomson and Kamler write that the abstract is not a summary—it’s actually an “argument, writ small,” and it must contain your central argument in abstracted form. You might say, “Well mine is a computer science article—I don’t really have an argument.” I imagine T & K would respond that any piece of academic writing can be abstracted into an argument. You are trying to persuade the reader that your computer science finding/development/algorithm contributes to the research/makes a difference in some way. And that’s an argument. Here are Thomson and Kamler’s moves; please refer to the chapter “Learning to argue” (pp. 83–106) in Detox Your Writing for more information and samples of ineffective/effective abstracts.

I am a big fan of Thomson and Kamler’s four-move abstract described in Detox Your Writing: Strategies for Doctoral Researchers (available as an e-book in our library). Their model works well for all types of abstracts, and it can also be used to kick-start your writing. Thomson and Kamler write that the abstract is not a summary—it’s actually an “argument, writ small,” and it must contain your central argument in abstracted form. You might say, “Well mine is a computer science article—I don’t really have an argument.” I imagine T & K would respond that any piece of academic writing can be abstracted into an argument. You are trying to persuade the reader that your computer science finding/development/algorithm contributes to the research/makes a difference in some way. And that’s an argument. Here are Thomson and Kamler’s moves; please refer to the chapter “Learning to argue” (pp. 83–106) in Detox Your Writing for more information and samples of ineffective/effective abstracts.

LOCATE: this means placing your paper in the context of the discipline community and the field in general. Larger issues and debates are named and potentially problematized. In naming the location, you are creating a warrant for your contribution and its significance, as well as informing an international community of its relevance outside of its specific place of origin.

FOCUS: this means identifying the particular questions, issues or kinds of problems that your paper will explore, examine and/or investigate.

REPORT: this means outlining the research, sample and/or method of analysis in order to assure readers that your paper is credible and trustworthy, as well as the major findings that are pertinent to the argument to be made.

ARGUE: this means opening out the specific argument through offering an analysis. This will move beyond description and may well include a theorisation in order to explain findings. It may offer speculations, but will always have a point of view and take a stance. It returns to the opening Locate in order to demonstrate the specific contribution that was promised at the outset. (Thomson & Kamler, 2016, p. 92)

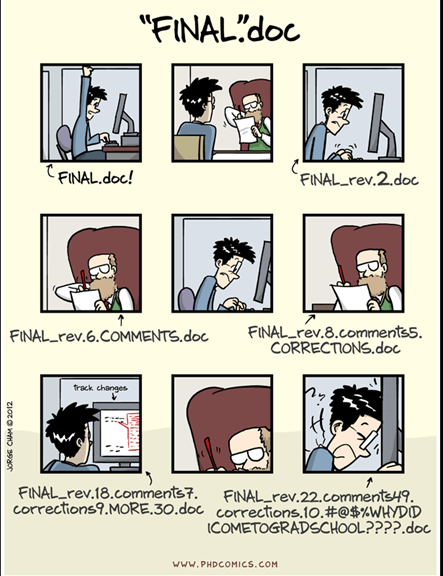

The authors encourage you to keep writing and rewriting your abstract throughout the broader writing process; each time, you will refine it further. Try preparing a draft abstract of your article/thesis, regardless of the stage you are at. You’ll be surprised at how it focuses your writing and cements your motivation. I’ve had more than one student tell me it worked to get them writing again after a dry spell.

Call for graduate student blog post writers!

A huge thank you to all of our student writers so far this year: Kaveh Tagharobi, Russell Campbell, Kate Ehle, Marta Bashovski, Cindy Quan, Jonathan Faerber, and Arash Isapour. Your writing resonated with so many of your fellow graduate students. Thank you for taking the time to craft wonderful posts and share your experience.

We need more student writers for the 2017/2018 academic year, so please consider writing for us. We need students from different disciplines and backgrounds and at various stages of study to volunteer to write for the blog. Your topic can be anything related to academic communication and graduate students; see the guidelines here. If you feel uncertain that your writing skills are sufficient to the task, please make an appointment with me cdrcac@uvic.ca I’ll be happy to coach you on how to improve your draft until we are both happy with it. As Peter Elbow says, “Everybody can write.”

Additionally, we need some specific topics covered this year, and perhaps one of these attracts you:

- The “thesis by publication” or article-based dissertation. This model, popular in the sciences and social sciences, requires that you write three or more “publishable” articles (plus weave them into a whole with intro/conclusion). Although the book-length dissertation is still with us, the article-based version is definitely a trend in our university, and I’d love somebody to write about it. Are you a student who is following this model or considering it?

- Writing in different disciplines. Perhaps you are writing an interdisciplinary thesis, dissertation, or article and you need to negotiate with supervisors from various faculties. How’s that going for you? We would love to hear from you if you’ve had this experience or you have written in different disciplines (say, you did your MA or MSc in one area and are doing your PhD in a different one). What have you learned about disciplinary differences in writing?

- Communicating with your supervisor. Okay, this may seem elementary, but some of us have struggled for hours to craft communication with supervisors or other professors. EAL students unfamiliar with the Canadian university context may find this especially difficult. Would you like to write about this challenge and some strategies that have worked for you?

Don’t want to write, but want to read about something in particular? Please email me to suggest a specific blog post topic: cdrcac@uvic.ca.

We are taking a break for August, and the next post will be published in mid-September. Happy summer everybody, and thank you for reading the blog.