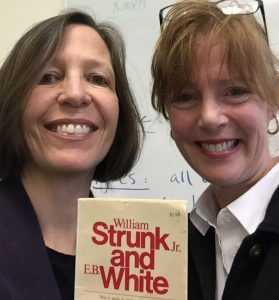

By Jacqueline Allan and Madeline Walker

Jacqueline Allan, a masters’ student in kinesiology with a background in recreation, started visiting the Centre for Academic Communication early in her program. When Jacquie , who is studying adult play, shared her novel approach to the literature review with us recently, I just had to see if she was willing to let the community experience it as well. Click onto the sound file to hear Jacquie’s journey up the mountain.

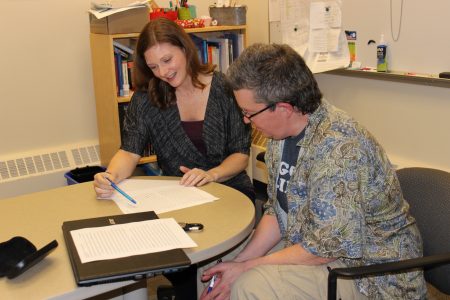

Earlier in the semester, Jacquie and I had a conversation about her life and her work.

Madeline: “Thank you for providing your literature review recording for us to enjoy. Can you tell me a little about why you wanted to study adult play for your master’s thesis?”

Jacquie : “I teach a lot of fitness classes, and I noticed that when I present something that’s playful, there are people who really resist that. They think, ‘I’m here to get a good hard workout, let’s just stay with what we know about exercising. Let’s not do anything playful.’ In fact, I’ve had people leave the class. So, I’m interested in what happens when we want to become playful. Or, why don’t we become playful?”

Madeline: “I love your question, ‘why are people resistant to play?’ I can relate as I used to be one of those people. Part of it was self-consciousness. What would people think? We’re not children anymore, I can’t look foolish. That was part of my resistance.”

Jacquie: “I think that’s a lot of it. People say I was a kid then, and I’ve left all that behind. Why is that? What are the forces acting on us as adults that don’t allow that? Is it still the work ethic thing, that if I am not working, I’m not seen as being productive? So it doesn’t have value? I am interested in that.”

Madeline: “When I first heard your lit review, you were on a hike, and there was birdsong in the background—you were embodying this spirit of play in your work, which I think is so wonderful. I wanted to know what was the spark to give you this idea? Was it, ‘I want to do a lit review and I want to record it, to make it a story?’”

Jacqueline made a wry face. “You just said I wanted to do a lit review; I HAD to do a lit review!” We both laughed about that.

Jacquie then described a childhood memory that informed her literature review journey: “I thought back to when I was a kid. I grew up on the North Shore of Vancouver, and we lived at the bottom of Grouse Mountain, and that was one of the things I did with my cousins, who lived in the same neighbourhood. We used to go down to the creek at the bottom of the mountain, and we would start going up the mountain, looking for Santa Claus. That was the culture we grew up in. It occurred to me that we didn’t really know where we were going. We knew that we were having fun, and this lit review is a journey for me into the unknown, into the wilderness.”

Madeline: “So that’s where you got the model for the journey up the mountain? “

Jacquie: “Yes. So I took all the people I was looking at in my research, and I could envisage them being at certain places along the way. One person that comes to mind is Brian Sutton-Smith [play theorist from New Zealand, 1924-2015]. I read his material for the literature review, and at one point I thought—wait a minute—I’ve met this person before! There was a prof who came to UBC and gave us a lecture for a convention or something, and I walked back with him and we were laughing and he looked like a surfer, and he had an accent. He reminded me of somebody who embodied playfulness! I could see him in the forest. He was with all the elves, just running around in this grove. So he takes a big part in this because he, for me, having met him, was playful even in his work. . . . And toward the end of the lit review, I came to the realization that I didn’t know anything!

I responded, “That means you’re very wise, Jacquie, when you know you don’t know anything!”

We chuckled about that nugget of truth voiced by Albert Einstein: “the more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.”

Jacquie: “Brian Sutton-Smith said that play is ambiguous–even Aristotle and Plato said that. We don’t really know what it is. Play is a noun and a verb in our culture. In particular, what is play for adults? As adults, we tend to know when we are not at play. To me, that means we know what play is. If you know the shadow of it, then you know what it is. But at the same time realizing this is so huge and I thought I would get to this literature review, and this would be the basis of a thesis I wanted to do, and I would think, ‘great, I’ve done it.’ Oh my gosh, no, not even close!”

The Wisdom of Ravens

Reflecting on her feeling of not knowing, Jacquie starts to describe her experience with ravens.

“I have met ravens on Grouse Mountain. One day, I was up there at the chalet where you can sit and look over the city. A raven came down and sat right there looking at me. This was the raven I had in my head. Speaking of wise–they’re so very wise. The raven looked at me:

‘You think you know what’s going on but you don’t have a clue! And furthermore this path is way longer and way more ancient than you ever thought.’

I know now that ravens in First Nations culture symbolize an awful lot, but one of the things is knowledge. I thought, well that’s interesting. The raven is holding all this knowledge, and it’s up to me to try to find out, but the raven had no intention of telling me any of the knowledge except to say, it will be revealed to you. First, you need to put in the work. So I’m at the bottom of the Grouse Grind, not at the top, and I need to keep going. That was the message from the raven.”

I know now that ravens in First Nations culture symbolize an awful lot, but one of the things is knowledge. I thought, well that’s interesting. The raven is holding all this knowledge, and it’s up to me to try to find out, but the raven had no intention of telling me any of the knowledge except to say, it will be revealed to you. First, you need to put in the work. So I’m at the bottom of the Grouse Grind, not at the top, and I need to keep going. That was the message from the raven.”

Jacquie thought for a bit then added, “Ravens also symbolize the subtlety of the truth. Am I looking for the truth of play? Will ever approach the truth? Or get close?”

Wondering with Jacquie, I offered the following thought: “Maybe there are multiple truths.”

Jacquie: “Good point. Ravens also symbolize the unknown. In fact, I wrestle with and have to get comfortable with and accept that I’ll never know the truth about play.”

I remembered what a favourite writer of mine said about the literature review. “Pat Thomson says that the literature review is about getting comfortable with ambiguity, with not knowing. You’ll never know it all. I love your attitude, of seeing it as a journey of revelation. Even if you only get a little bit of it, there’s still a sense of appreciation. Sometimes we get arrogant as academics, thinking we can capture all this information, but in fact it’s always changing and dynamic, and it’s impossible to know it all.”

Jacquie admitted that this was a surprise to her.

“Jacquie,” I said, “I know you are an accomplished jazz vocalist. Is that what you do for play?”

Jacquie: “It is playful, but within a massive structure. So knowing the structure is super important, and improvisation is all part of jazz. So that becomes the playful part but within this really tremendous structure. So for me personally, playfulness is an attitude. I have a strong feeling that all of creation is playful, and the fact that we as humans don’t get that is kind of our problem. And so I look for that, every single day, and I look for the people–you recognize somebody who has a playful spirit. Most day to day situations can be turned into playful situations. But that makes going through it fun; why not have fun? We’re all in it together. To do what we do individually to the best of our abilities. Let’s just have fun together. It’s very social for me as well. I can be playful by myself, you know I like physical recreation, but being playful with other people is where it’s at.”

Madeline: “So playfulness is an attitude for you?”

Jacquie clarified: “It’s actually a behaviour trait. Most of the researchers would distinguish play as one thing, but playfulness is something different. One researcher, Gordon, says her feeling is that playfulness can be learned or re-learned as an adult, and that fascinates me. What are the conditions under which a person learns for the first time or relearns how to be playful in their life?”

Jacquie and I agreed this seemed hopeful—that adults can re-learn their playfulness.

Jacquie’s top three tips for writing a literature review

I asked Jacquie to share her top three tips for a student who says, “I have to do a lit review and I’m terrified! What should I do?”

Jacquie responded without missing a beat: “Seek help at the Centre for Academic Communication. Those people know what a literature review is, and they can give you information on how to approach it right from the very beginning. They can give you tons of resources. That was so important to me. It was vital to me, not having done one before.”

Madeline: “Thanks for the plug, Jacquie!”

Jacquie : “Second, be looking at a topic you absolutely love because it can be onerous, and reading research is a bit of a process, so just stay with your loved topic. The third one is to have fun with it because it is a journey. In Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck says ‘you don’t take a journey, the journey takes you.’ So recognize that right off the top.”

Jacquie started to gather her things to go. Time had slipped by quickly because we had been playing. “Thank you for the opportunity and the assistance you’ve given me.”

Thank you, Jacquie , for sharing your journey through this interview and your recorded literature review. Many readers will feel inspired to welcome playfulness into their lives after they read this. I know you inspired me!

Photo of Jacquie by Malakai Design Photography

Photo of Raven: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_adult_raven.jpg

By Bombtime [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

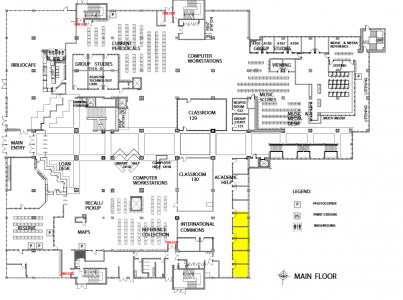

We’d love to see you.

We’d love to see you.

Graduate students: Tell your writing story

Graduate students: Tell your writing story