By Madeline Walker

Dr. Thomas Darcie (also known as Ted) joined UVic in 2003 after a long career at Bell AT&T and is currently a Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. He is known as a leader in the development of lightwave systems for analog applications in cable television and wireless systems.

One morning in early June, I had the opportunity to meet with Ted in his office in the Engineering Office Wing. Dozens of articles—evidence of Ted’s productivity—were spread across his desk. A cool breeze entered the open window.

Ted has supervised many graduate students in Engineering over the years, and I wanted to hear his ideas about writing in his discipline.

“How is writing in Engineering different from writing for another disciplines?” I asked.

“In Engineering, you’re trying to get across a complicated idea as succinctly as possible. I think in other disciplines they tend to use more words to express things. Certainly when there is a lot of mathematics involved, you try to let the mathematics tell the story, and you’re writing words to support the mathematics.”

Ted and I talked about the kinds of challenges writing presents for his students. “I see challenges at every level of the writing process,” he said. “There’s the top level, the organizational structure of the story to be told. Then this breaks down to paragraphs—what is supposed to be in a paragraph and what separates paragraphs. Then there’s sentence structure, use of words, punctuation, syntax. I see challenges for writers at all these levels.”

“How do you help students face these challenges?” I wondered. “Do you work with them on their writing?”

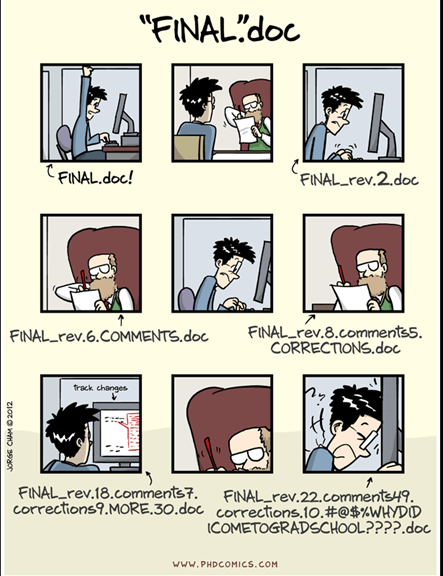

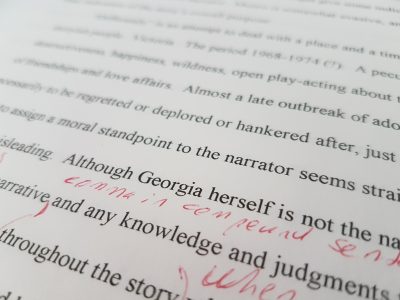

“I do. We spend quite a lot of time cleaning up drafts. I mark-up drafts – I take a document and address all the levels at the same time. The first cut is the organization cut – what goes where. Then after the organization makes sense we break it down. It takes time, and in extreme cases I’ll work through several drafts with a student.”

I was curious about what Ted identifies as the biggest problem in graduate student writing. He used a metaphor to illustrate how students sometimes miss the point of writing: “People tend to want to write about what they spent their time doing whether or not that aligns with the story that needs to be told. A student might spend 80% of their time trying to polish something without breaking it, and they succeed. Then they spend 80% of their manuscript writing about the polishing, but what the reader wants to know is the outcome.” Ted’s example tweaked my memory; I’d seen corresponding situations in other disciplines, for example the data-driven thesis in the social sciences. A student might discuss her data for pages and pages without drawing any conclusions about it.

We moved from talking about problems to talking about successes. I asked Ted what characterizes the best engineering writing by students. “It’s well organized. Organization is key,” he answered. “In organized writing, the writer establishes a direct line between the introductory objective, the analysis, the results, and the meaning. The direct line is very important.”

I asked Ted to tell me more about the “direct line,” an intriguing phrase that reminded me of the “red thread” that some people refer to in argument-driven writing. “Well,” he said, “a technical manuscript is a concatenation of results, graphs, and equations, and you can tell the story with no words by lining up your graphs, figures, and equations in the right order. You can fill in the blanks between by joining those visuals. Visuals are telling the story, the words are just supporting the visuals. I badger my grad students to give me the story line in the visuals. Write in point form between the pictures, then expand each point into a paragraph. I’d much rather see a concatenation of 20 pictures telling a story than a concatenation of 20 paragraphs telling a story because I know which one would be better organized. You don’t need words to tell a story. Once the pictures are lined up, it’s easier to get the words right.”

The breeze from the open window lifts the top pages of the articles blanketing Ted’s desk. I thank him for his insights and go out into the bright day. I muse on disciplinary writing differences. My own love for art helps me know at a deep level that you can tell a story without words. I just hadn’t thought about how that idea can be applied in academic writing. I will now approach the engineering and math students I meet with this new perspective. For these disciplines, the word is often helpmate to the picture, and as Ted says, “once the pictures are lined up, it’s easier to get the words right.” Thank you Ted, for helping me to see writing in a new way.

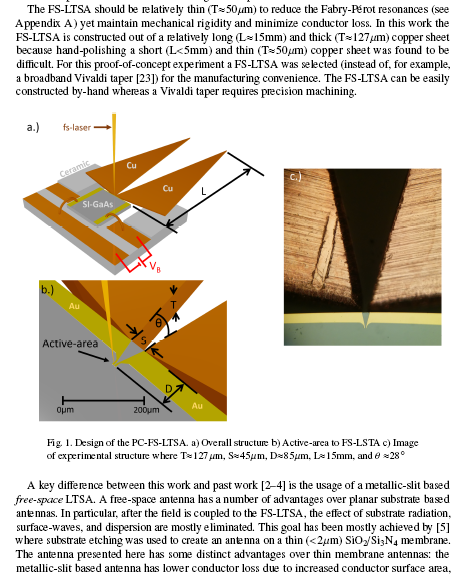

Credit: Smith, Jooshesh, Zhang, & Darcie. (2017). THz-TDS using a photoconductive free-space linear tapered slot antenna transmitter. Optics Express, 25(9). 10118-10125. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.010118, p. 10120.