By Emily Arvay

Q: Why is time management so hard?

A: There are many different reasons for why time management is hard. Lots of students might wait until things are already off the rails to think about time-management. And when you are in triage mode and putting out fires, taking the time to create a time-management plan can seem counter-productive. Also, students sometimes create vague or unreasonable time-management plans that set them up for failure. So within a week of setting up their plan, they are already behind and then just abandon the plan.

Often, time-management plans are unworkable because the student has neglected to really think through and spatialize their course requirements in enough detail. Frequently, students already in a state of panic about missed assignments and late penalties might find it challenging to think through complex processes in a step-by-step way due to elevated cortisol levels that often come with anxiety, not to mention sleep deprivation from pulling successive all-nighters.

Ironically, one of the great benefits of building a reasonable time-management plan is that it can greatly reduce that sense of panic by restoring to students a sense of control over their lives – once the plan is in place, a student need only review the items for a single day, hold those items in mind, and let go of the rest. So, to use a metaphor, instead of staring at the top of a mountain wondering how can I possibly climb that, a student need only look to the closest tree and hike to that point.

More importantly, having a good plan in place can prevent burnout because it enables students to give themselves guilt-free permission to set school-related activities aside. If you have ticked all of your to-do boxes for the morning, you can go for that walk to the ocean. Or, if you have completed the task you needed to do after dinner, you can binge-watch whatever new series you enjoy without feeling that you are somehow not doing enough.

One added perk that comes with good time-management plans is that students often find interpersonal tensions related to poor well-being or the perception of overvaluing school at the expense of significant relationships really improves, which can generate a supportive and motivating feedback loop.

But setting aside the impact of stress, anxiety, sleep deprivation, and interpersonal strain, more commonly students may not give much reflective thought to how much time it takes to complete different tasks and then do the math to see what that process looks like when spatialized.

That is, not many students time themselves to see how long it might take to read one page of a challenging but not overly difficult academic article, or how long it might take to write 250 words of an essay. So, in underappreciating how long certain tasks might take, students also can set themselves up for failure in terms of time-management.

Most often, when I ask to see how students are presently managing their time, what I see spatialized are assignment deadlines, marked in an agenda or on their computer calendar, or on the whiteboard. What I most often see are a string of dates for submission: something along the lines of submit English research paper today at midnight and that’s it. Or a student may dedicate large coloured squares of time to different subjects: on Mondays, there might be a large blue square for Math in the morning and then a large green square for Biology after lunch, but without any indication of what particular tasks are intended to be completed during those intervals.

What is notably absent from most time-management plans are the most important elements: catch up times and necessary activities such as buying groceries, eating, sleeping, getting exercise, socializing, doing things that make you feel good about your life.

Also, sometimes what students “label” poor time-management might actually be something else, such as procrastination due to perfectionism, or writer’s block due to a fear of failure seeded by familial expectation, or a sense of dread created by overly-critical thoughts, or poor self-discipline from a lack of intrinsic motivation or greater sense of academic purpose.

So for students who find it difficult to stick with an otherwise reasonable and well thought out time-management plan, it might be worthwhile to give some thought to what, in particular, is behind poor time-management. In those moments when a plan is abandoned, it might be worthwhile to draw greater awareness to what kinds of thoughts or feelings might be surfacing to prevent the completion of that task? If the underlying issue is perfectionism, or fear of failure, or lack of purpose, there are related strategies students might use to overcome those challenges too.

Q: What are some effective strategies?

A: To create a time-management plan with enough detail, I would forgo sticky notes, or those tiny paper planners, or even a white board in favour of a some type of electronic planner, if possible. This strategy often allows students to squeeze in more information, cut and paste items efficiently, and even automate important reminders. But really, use whatever system will work, since there is no point in generating a time-management plan that is not regularly consulted and, for some people, the physical reminder of a white board is key.

I would recommend that students build comprehensive time-management plans in the first week of the term when they have access to all of their course syllabi. First, I would recommend coding in necessary items, such as meal times, ideal start and stop times, times for exercising, times for commuting to work, times for enjoying hobbies, times to enjoy friend or family commitments. Perhaps you might decide to take each Saturday off to recoup from school?

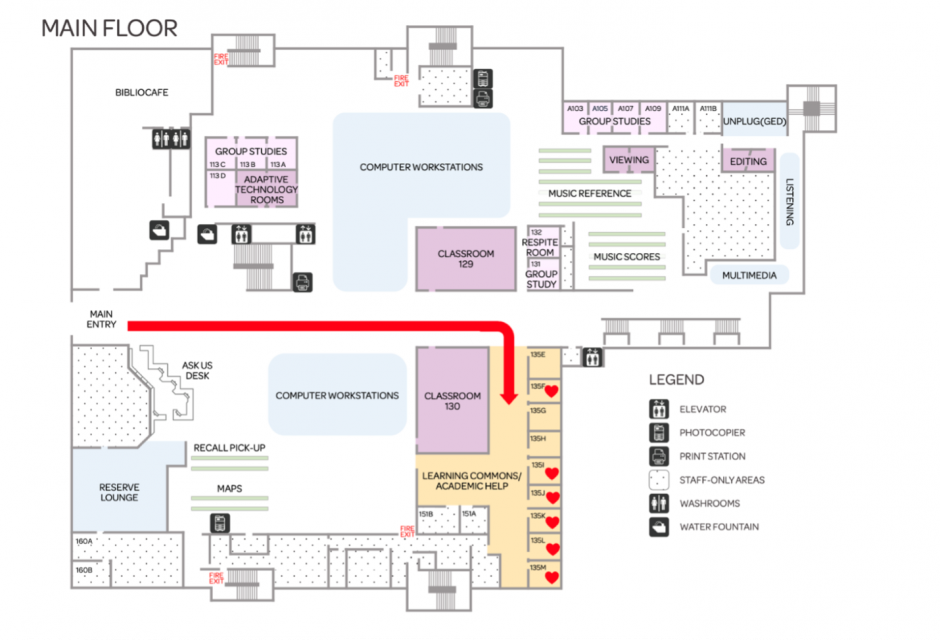

Then code in major deadlines, noting the weight/value of each, time they are due, preferred method of submission. Then spatialize, working backwards from the deadline, all the tasks required to complete that assignment. So if the assignment is a seven page research paper requiring you to cite ten academic sources, code in the time to write each of those seven pages, time to create your outline for writing, time to collate notes and quotes from selected sources, time to read those ten sources, time to locate and upload or print those sources. Once this process is complete, time also to book an appointment with a CAC tutor, and time to integrate their feedback into your final draft before submitting that assignment.

I would do the same process for each major assignment, leaving in one hour of catch up time for each hour of time worked so that if things really start to slip sideways, if there is an unexpected illness or extenuating life circumstance that pose a setback, there is still plenty of wiggle-room left to shift items around.

Likewise, I would ask each student to give some thought to how long they can reasonably focus. Some students prefer to work for two-hour intervals without interruption followed by a long break. Some students find they focus best in 25 minute intervals with 5-10 minute breaks. Some students do their best work early in the morning, with their first cup of coffee. Some students work best after dinner into the wee hours of the night. Regardless of whether you are an early bird or night owl, you might give some thought to what time of day you tend to sustain greatest focus, think most clearly, and can produce your best work. If you can identify that time, I would complete your most challenging task then.Likewise, you might give some thought to the hours of your day that you tend to feel more foggy or sluggish (for many this is right after eating a large meal, or right before bed) so you might want to devote your easiest work to those periods of time?

You might also think about ways you might incentivize the completion of hard tasks. Perhaps you might go for a run, then sit down to complete a hard task. Or perhaps you might complete the hard task knowing that, once completed, you can reward yourself by listening to your favourite song, or watching comedy on Youtube, or eating a bowl of ice-cream.

Q: What should a student do when they simply DON’T have enough time?

A: If you find yourself in triage mode, it might be wise to adopt a “good enough” mentality that is dispassionately strategic. To this end, you might consider….

- Which assignments are worth the least? Which readings do you NOT have to read? Which feed into assignments? Which readings can you skim?

- Read the abstract and headings. Read only the intro and conclusion and forget the middle. Read topic sentences. Read phrases that are italicised or in bold. Read (peer-reviewed) reviews of that work to obtain a scholarly synopsis (rather than online cliff notes, etc).

- Tag team with a trusted classmate. You read one article and they read the second; you share with each other what you have learned.

- Ask instructors for extensions as soon as you realize you are in an impossible time crunch. Avoid asking for extensions on the day of your assignment deadline. Keep your email to your instructor simple and straightforward. Include your full name, course section, and V number. You do not need to explain why you are requesting an extension beyond using a phrase such as “difficult extenuating circumstances.” Suggest an alternative deadline, one that gives you more time than you need to avoid having to ask for an extension on your extension! Thank your instructor for their time and consideration.

For more time-management strategies, you might listen to this podcast.

About the author

Emily Arvay completed her PhD at the University of Victoria in 2019 with her thesis “Climate Change, the Ruined Island, and British Metamodernism.” Since then she has worked as a Learning Strategist and EAL Specialist at the University of Victoria. She is currently conducting further research on the intersections between literary metamodernism and contemporary climate fictions.

Emily Arvay completed her PhD at the University of Victoria in 2019 with her thesis “Climate Change, the Ruined Island, and British Metamodernism.” Since then she has worked as a Learning Strategist and EAL Specialist at the University of Victoria. She is currently conducting further research on the intersections between literary metamodernism and contemporary climate fictions.