By Gillian Saunders

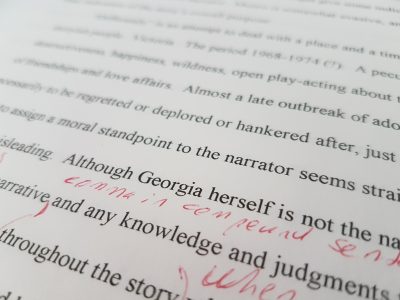

It wasn’t so long ago when I found out that I didn’t really know how to use a comma. I mean, I knew how, but I didn’t really, really know. I could put them in the right place about 95% of the time, but not explain why I was adding them or choosing not to. Sound familiar?

I wasn’t a poor writer, making word salad with a careless handful of commas tossed in; I’d been admitted to a graduate program in English Language and Literature. And I didn’t know how to begin to fix this problem. At this point, the finer points of punctuation seemed mysterious and probably unlearnable.

As an English as an Additional Language Specialist at UVic’s Centre for Academic Communication and as an instructor, I meet a lot of students experiencing this same frustration. Writers who learned English as an additional language may be at an advantage: for the most part, they have been “taught” a lot of what they need to know to be able to master the use of commas and other fun and useful things like colons and semicolons with relative ease. In order to know whether you need a comma in any given situation, you need a functional range of metalanguage: relative clause, dependent clause, conjunctive adverb, etc. Native English speakers under a certain age, however, were mostly just told to throw a comma in when they “felt like they needed a pause,” which, unfortunately, isn’t a real rule of comma usage. As adults pursuing graduate degrees, not having been taught real rules isn’t doing us any good now. In fact, it’s kind of embarrassing.

“What am I supposed to do about it now?” you might be wondering. Here’s the abridged version of how I’ve filled my own vacancies in the punctuation and grammar puzzle: first and foremost, my education is in a very reading- and writing-heavy field. I studied writing and linguistics with some very inspiring and knowledgeable instructors, and then I started teaching grammar and composition myself. At that point, I had to learn everything there was to know, or else risk being shown up by students who had mastered not only their own first languages, but mine as well, and better than I had. I completed a Certificate in Editing by distance. I read books like Michael Swan’s Practical English Usage, Strunk and White’s classic The Elements of Style, and everything by Kate Turabian and Diana Hacker. I Googled. A lot. “Which vs. that?” “What is an appositive?” I tugged at the knots of obscure grammar forum threads until I was satisfied that I could explain when and why you need a comma before “such as.” I started reading my work, and the work I edited, aloud, with verbalized punctuation: “The semicolon has two main uses COLON it separates long items in a list COMMA which may also contain commas COMMA and it joins two independent clauses that are closely related PERIOD.” I questioned my identity as a writer, as a native English speaker, and in other areas of my life. Had I also been singing the wrong words to my favourite songs at the top of my lungs in the car all along? (I had.)

the abridged version of how I’ve filled my own vacancies in the punctuation and grammar puzzle: first and foremost, my education is in a very reading- and writing-heavy field. I studied writing and linguistics with some very inspiring and knowledgeable instructors, and then I started teaching grammar and composition myself. At that point, I had to learn everything there was to know, or else risk being shown up by students who had mastered not only their own first languages, but mine as well, and better than I had. I completed a Certificate in Editing by distance. I read books like Michael Swan’s Practical English Usage, Strunk and White’s classic The Elements of Style, and everything by Kate Turabian and Diana Hacker. I Googled. A lot. “Which vs. that?” “What is an appositive?” I tugged at the knots of obscure grammar forum threads until I was satisfied that I could explain when and why you need a comma before “such as.” I started reading my work, and the work I edited, aloud, with verbalized punctuation: “The semicolon has two main uses COLON it separates long items in a list COMMA which may also contain commas COMMA and it joins two independent clauses that are closely related PERIOD.” I questioned my identity as a writer, as a native English speaker, and in other areas of my life. Had I also been singing the wrong words to my favourite songs at the top of my lungs in the car all along? (I had.)

Learning the “right way” to use punctuation (and the correct lyrics to all my favourite 80s and 90s songs) clearly took time and the kind of dedication that may not be available to you when your literature review is due next week. Thankfully, there are other options available. First, get a diagnosis from someone who knows a lot about these things. Maybe you’re guilty of conjunctive adverb abuse because you’ve got them confused with subordinating conjunctions. Maybe you’ve never thought about restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. Half the battle is just knowing what to Google.

It may seem painful at first, but picture yourself at some point in the future when it pays off: your perfectly punctuated cover letter just got you your dream job. You didn’t have to hire an editor before you submitted your article for publication. You’ve met the girl of your dreams online; her profile said she only dated people who texted with correct punctuation, and she really meant it. Good punctuation matters to a lot of people, more than you might think, but at the end of the day it’s up to you how accurate you need your writing to be and how much you are prepared to invest in your writing practice. Like doing yoga or learning how to knit a sweater, it takes time and dedication to develop the skills and ability you need in order to have a practice you’re satisfied with. A good practice requires a good instructor that you trust, clear instructions, the ability to detect errors, the skills to be able to fix them, the confidence to take risks, and the humility to ask for help when you’re not sure what you’re doing. Who can you ask? The CAC. We’re here to help!

Gillian is an English as an Additional Language Specialist and Business English and Communications instructor at UVic, and has taught in Canada and South Korea. In her spare time she can be found reading about grammar and English language teaching and patting herself on the back for not pointing out every single writing error she encounters during her day.

Gillian is an English as an Additional Language Specialist and Business English and Communications instructor at UVic, and has taught in Canada and South Korea. In her spare time she can be found reading about grammar and English language teaching and patting herself on the back for not pointing out every single writing error she encounters during her day.