[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.7.7″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″]

As part of my role as a Textual Analysis Expert in the DSC, I investigate different ways of analyzing texts and visualizing data. I recently started working with StoryMap JS, a free, open-source, web-based tool for creating narrative maps. I chose this tool to help me solve a problem related to my research into Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, first published in London in 1794.

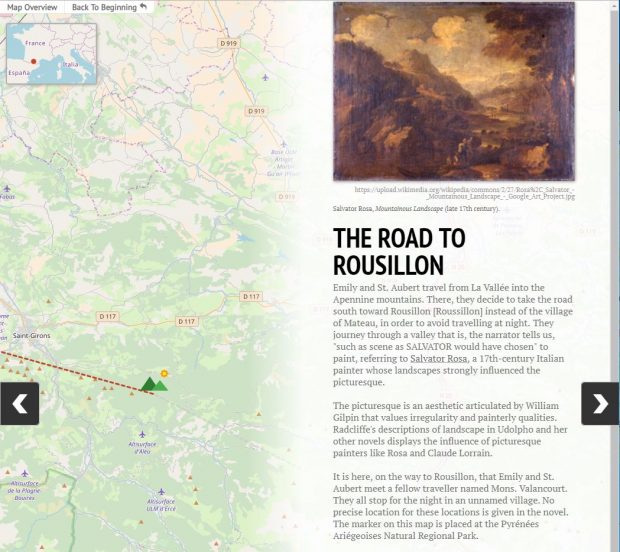

Udolpho is known among literary scholars for its painterly descriptions of the landscapes that the heroine, Emily St. Aubert, passes through on a long journey from her home in Gascony region of France to the dreadful Castle of Udolpho, hidden in the Apennine mountains in Italy. Although the novel is preoccupied with travel and with the variety of landscapes it provides, it can be difficult for readers (particularly those of us who have not had the benefit of a Grand Tour) to visualize the journey. It is even more difficult because, although some of the locations named are well known–such as Toulouse and Venice–others are less familiar: small unnamed villages, towns that have since been renamed, and fictional locations. One of my goals in creating this map, then, was to help myself and other readers and scholars of Udolpho understand the nature of Emily’s journey and its role in the novel.

To create a Storymap, you need a list of locations and some narrative to accompany them. I realized quickly, though, that generating this list of locations from my text would be a challenge.

The novel mentions several places that are not part of Emily’s journey. Emily’s aunt and uncle tell her and her father about their estate called Epourville, for example, but she does not travel there with her father. Many significant locations have no formal name, such as the mountain convent and the shepherd’s cottage in which Emily and St. Aubert take shelter. So, although it is possible to extract a list of proper nouns from the text using natural language processing and isolate the names of places, that list would not be very useful for my purposes. In the end, I decided to take a low-tech approach to analyzing my text, and just read it through. Being familiar with the novel is helpful because it means I can use my knowledge of Emily’s journey to skim the text more efficiently for significant locations. I also used an electronic version of the text from Project Gutenberg so I could search for mentions of various place names and find clues to their location more efficiently.

Finding location clues turned out to be the most time-consuming, but rewarding, aspect of this project. I quickly realized that in addition to generating a list of locations, determining where those locations should be marked on the map was another challenge. Some locations are simple, such as Venice. Others are more challenging, even when they are real, named locations. Determining where to place those markers on the map required in-depth analysis of the text as well as a good deal of deductive reasoning. For example, Emily’s journey begins at her family estate of La Valeée. This is a fictional estate, and no precise location is given in the text, but it is imagined in reference to real locations. To figure out an approximate location for the estate, then, I found and analyzed location clues in the text. I needed to infer an approximate location by the following clues provided in the text:

- La Valée is in Gascony, to the north of the Pyrenees mountains.

- It is south of Guienne.

- It is west of Languedoc.

- It is east of the Bay of Biscay.

- It is on the banks of the Garonne river.

Upon analyzing the account of the first stage of Emily’s journey, from La Valée to Languedoc, I deduced some additional clues:

- La Vallée is in a remote part of the country (that is, far from Paris), but since Emily’s aunt and uncle visit them on their way home to Èpourville (the location of which we do not know) from Paris, La Valée must be on a path between those two locations.

- Because Emily and her father decide to travel through the mountains, rather than along their base, La Valée is likely south of Languedoc. If it were north, they could avoid the mountains altogether.

- Since Emily and her father follow the Garonne up into the mountains and then travel east, La Valée must be slightly west of the river.

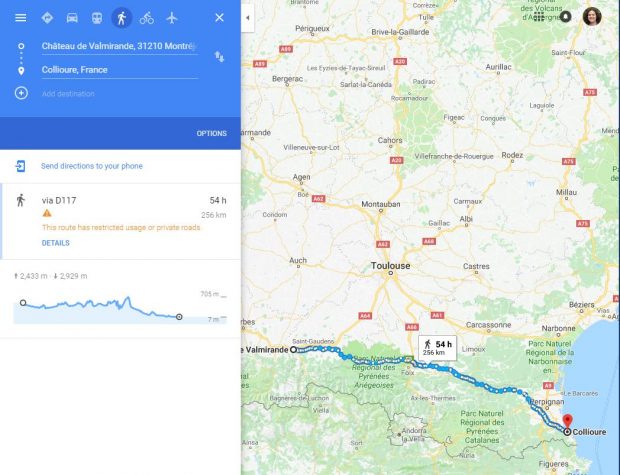

This information narrowed down the possible location of La Vallée to somewhere near Lourdes. However, in order to determine a more precise location, I needed to work backwards from their arrival in Rousillon to calculate the distance and duration of the journey. Roussilon is a region near the shore of the Mediterranean, and the endpoint of this stage of their journey is a town called Collioure. The duration of their journey cannot be determined precisely, since they stop for several days to allow Valancourt to recover from an injury, but we do know from the account of their journey and their efforts to find accommodation that they spend five days travelling. Their pace is likewise difficult to determine precisely, but we know that they tend to travel from dawn until dusk and go at a leisurely pace to accommodate St. Aubert’s ill health and to appreciate the scenery. I’m estimating that they travel about 8-10 leagues per day, or about 31 to 39 km. This puts their entire journey from La Vallée to Collioure at 155 to 195 km. I used Google Maps to find a location that fit all these criteria, and decided to place the marker for La Vallée at Chateau de Valmirande, near Montréjeau. Given the information in the text it is impossible to be certain that these deductions are correct, but I was pleased to discover that on the D’Anville Map or Europe from 1794, the region surrounding Chateau de Valmirande is called Les Vallées.

This process of analysis and deduction that I’ve described produced one point on the map of Emily’s journey, and had to be repeated for almost every other point. I was surprised at how difficult it was to produce this list of locations and how much close reading and deductive reasoning it required, not to mention the amount of research: I looked up the geographical features of this particular region of France, the Garonne, and the Pyrenees; investigated standards of measurements in pre-revolutionary France; and looked for medieval castles using Google Maps and Wikipedia. There was good deal of research involved in finding sources, too: for the historical map, I used one created by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville in 1794. To look up place names, I consulted Google Maps and a Gazeteer from 1793.

I began this map thinking it would be a straightforward project for learning StoryMap, and it was, once I had done the analysis needed to generate my locations. The tool itself is very user friendly and intuitive; the challenge lies in working with data that is fuzzy, imprecise, and resistant to certainty. This fuzziness can be frustrating, but it also leads to all sorts of fascinating questions. Trying to locate fictional places on a map of the real world made me think about the relationship between real and imagined spaces, for instance. I started to wonder why Radcliffe chose describe the novel’s landscape the way she did, and why some named locations are real and others not. I also realized the impossibility of recapturing the world of 1794, when so many images I looked at included cars, power lines, and other technologies unthinkable in Radcliffe’s time. And, of course, I started to question the assumptions underlying the very creation of such a map, including the assumption that the journey is mappable at all, and that it conforms to the realities of space and time.

Finally, making this map prompted me to consider the nature of place in fiction. Why are some locations real and some not? What is the effect of evoking locations that cannot be located, or that virtually no readers or scholars will try to locate, as I have done? What does the description of the location evoke, and how does having a more precise location alter this? How does mapping the journey affect our reading of the text, and to what effect?

So far, I’ve only mapped the first stage of Emily’s journey, and found it to be far more work than I thought, but also much more complex, challenging, and rich in interpretive possibilities. My next step will be to map her journey from Rousillon to Udolpho, and the horrors that await her there.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_post_nav prev_text=”%title” next_text=”%title” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ global_module=”4392″][/et_pb_post_nav][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]