Recently, we digitized a series of notes and edited typescripts for Langrishe, Go Down, a novel by Aidan Higgins, first published in 1966 and later adapted for BBC television in 1978 by Harold Pinter. As I worked through scanning the many iterations of the story, I was struck by what we’ve lost to the digital era of writing and editing: insight into the author’s personality.

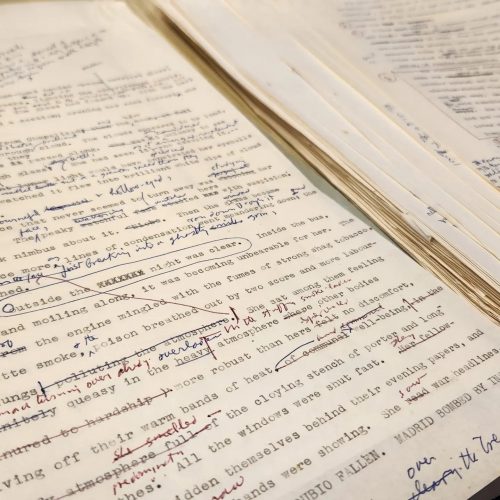

The notebooks and typescripts are full of marginal doodles, scribbled notes and directions for future edits, pages cut apart to re-order the text, and sometimes questions about what is to be cut or kept. While modern writing software, apps, and even this blog platform can track revisions, they don’t offer nearly the level of insight that we can draw from these sheaves of yellowing paper.

In addition to those typescripts edited by Higgins, this collection includes several typescripts with corrections by John Calder. Calder was Higgins’ editor and publisher and was a remarkable figure in his own right. To see his fingerprints in this work was a welcome surprise.

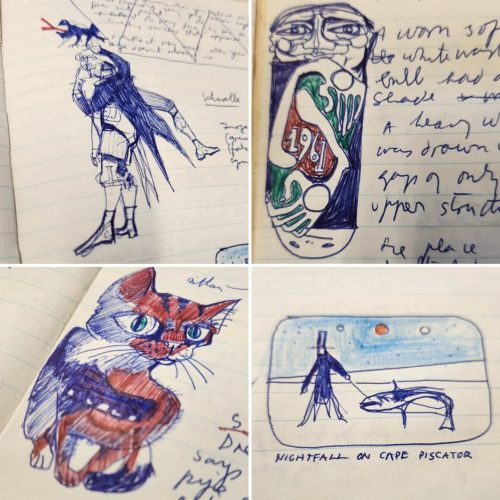

For researchers, it’s a different way to see the author and his intentions. While tracking revisions can show the author’s decisions about the text, there are no digital doodles that lend context to the writing or otherwise reflect the author’s state of mind. The doodles are often completely unrelated to the nearby text but nonetheless offer glimpses into the mind and creative process of someone who once said he would have been a painter had he not become a novelist.

Doodles aside, even the way something is crossed out can reveal whether the decision was made easily and quickly or was perhaps a more difficult debate — as when we see corrections to corrections. Sometimes, if we are lucky, we might see evidence of the author’s very humanity in a coffee or tea stain, or a grease mark left behind from an errant muffin crumb.

In addition to the personal touch these artifacts offer, there is also a much better sense of the way the author wanted the text to flow. Whether a single word is changed or an entire paragraph or chapter excised, there is a concrete record to view rather than reconstructing the changes through tracked edits. The one thing these cannot tell us that a digital record can is when each edit was made. While we can guess from the color of ink used that edits in red were made at a different time than those in blue, we may never know for certain which came first or how much time elapsed between the edits.

These notes and typescripts are about 65 years old; one can only imagine where technology will take us in the next 65 years. Will researchers consider our contemporary track-changes documents quaint and cherish them as lovingly as we now cherish these handwritten edits and embellishments? We can make educated guesses but only time and future researchers will be able to provide an answer.

Browse the Aidan Higgins Collection at UVic Libraries

Additional reference: Sweetman, Rosita, “Aidan Higgins at Eighty,” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 96, No. 384, Realities of Irish Life (Winter 2007), pp. 445-451

One thought on “Scribbled edits and marginal doodles”

Thanks for much for posting this, Page, and for your work on the archive. It is great to see Aidan’s doodles reaching a bigger audience. His letters within the family often had some too, and he always ended his letters with a large wine glass with a red blob in it!

Perhaps this will also encourage people to read Langrishe, Go Down, his best-known novel, which has weathered very well over the years.

Comments are closed.