In our first shipment of specimens we received an American pika, and a muskrat. Even before starting to scan, we suspected that the fur would give us some trouble.

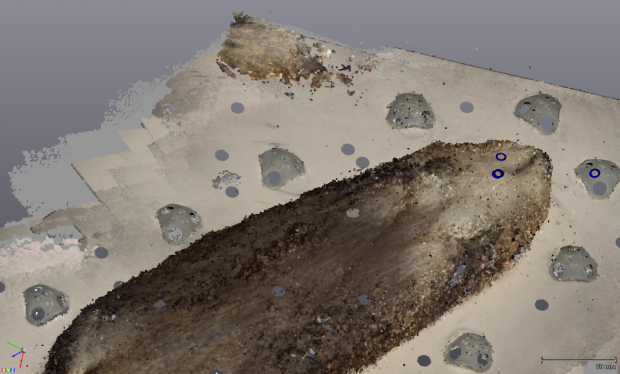

One of the first problems I encountered in trying to scan the muskrat was to even get a scan. Typically, when doing a 3D scan, you start in the center of the object and work your way out. The problem when using this methodology on a fur covered specimen is that the scanner struggles to distinguish fur from fur. When adjustments to the shutter speed and resolution didn’t produce better results, I was forced to rethink my scanning tactic. In an attempt to at least start a scan, I placed all of our positioning turtles around the muskrat’s body at varying angles. “Turtles” are small plastic triangles with reflective positioning targets placed on each side at 45° angles. The positioning targets are a standard size and their reflective surface makes them easily distinguishable to the scanner. They act as anchors around the object to help the scanner find its relative position. With the turtles in place, I started working from outside the object by capturing all targets in my initial scan and then slowly working my way in from the edges. This worked well until I was scanning the center of the muskrat’s back. As I reached the center, the scanner kept losing its place because it was relying heavily on the location of the targets, since the fur does not vary much in colour and texture. Normally, targets can also be placed on the object to assist the scanner when the object doesn’t have enough distinctive natural features but I was hesitant to place adhesive positioning targets on the back of a delicate 80 year old specimen.

After brainstorming with the other members of the Digitization Center, we came up with the idea of sticking the targets to some clear plastic then cutting out the targets so that they could be placed on the surface of the specimen without damaging it. Once the problem of being able to complete the scan to the centre of the body was resolved, the next challenge appeared.

“Ghosting” is a term used to describe what happens if the scanner becomes confused about its orientation relative to the object and begins creating information where there shouldn’t be any. This problem will often occur on objects where different sections look similar or if you move the scanner too quickly between targets.

Since the scanner was already having trouble distinguishing the difference between different patches of fur, and the targets had been placed far apart on the body to minimize any information that would be hidden from the scanner plus thirteen identical turtles now encircled the specimen, the perfect conditions for ghosting had been created. When ghosting occurs away from the object being scanned, it can be deleted and ignored, but if it occurs on or near the object, an entire scan can easily be ruined. Fortunately, we had encountered this same problem, although to a lesser extent, on our first furry creature, the American pika. After re-configuring the targets, moving the turtles, and making sure to capture all of the targets in the initial scan, I was able to eliminate the ghosting, or at least contain it to an area outside of the desired scan.

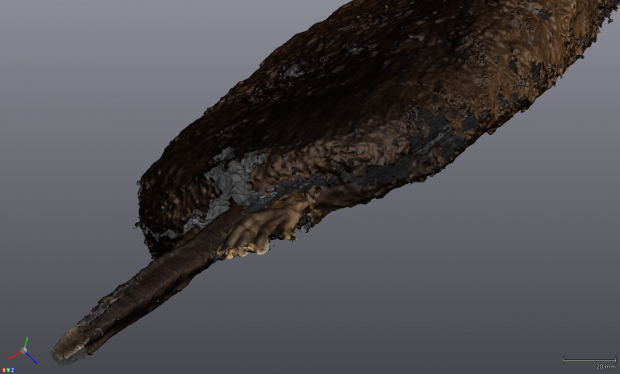

The biggest obstacle to scanning the muskrat was simply the texture of its fur. Not only was the each strand of hair thick, it was also long and protruded a fair distance from the muskrat’s body. As mentioned in my last post, objects with thin and protruding parts are the most difficult to scan. Unfortunately, the fur on the muskrat specimen is the perfect combination of these two elements making it very difficult to scan. To scan properly, the 3D scanner has to rely on the fur being clumped together in a way that it can read it as a solid object. In sections of the body where the fur lays flat, for example, against its stomach, the scanner was able to treat it as a solid surface by recording small depressions in its fur coat. The limitations with scanning fur quickly became apparent however, as soon as the end of the muskrat’s body was reached.

Now, I’m not sure how close you’ve ever gotten to any type of small rodent, but if you have, then you probably immediately started wondering about the nearest location where mouse traps are sold. Instead of running to the nearest store, if you were to have taken a look over your shoulder, you may have noticed how all the hairs surrounding the tail and ears stick out a fair distance from the rodent’s body. If the hairs are thin, this isn’t a problem as the scanner simply ignores them, but if the hairs are thicker they will block any light from reaching the body. Since the 3D scanner functions by calculating the distance of light emitted by the scanner reflected back off the object, it can’t receive any information about an object from a shadow. The minute difference in the distance between hairs is simply beyond the scanner’s capabilities. Unfortunately there is no easy way to solve this problem, and the only solution I was able to come up with was to scan the muskrat in small sections from every angle and combine all the scans together. Despite the setbacks and problems encountered, I was able to get an accurate 3D representation in the end.

3D model of the muskrat specimen: