Two of our learning strategists, Brodie and Hannah, offer their thoughts on the timely topics of procrastination and stress. If you want to consult with a learning strategist about time management or goal setting (in-person or on Zoom), book an appointment: https://uvic.mywconline.com/

Some Thoughts on Procrastination

By Brodie

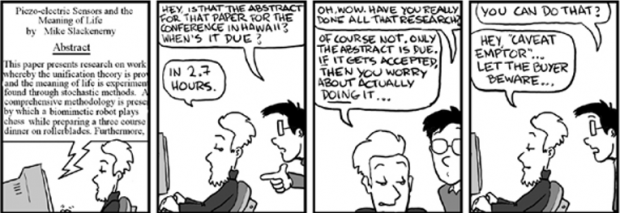

If you are anything like me, at this time of year just after reading break, it is easy to put your writing on the backburner and procrastinate. I am sure that we are all master excuse-makers by now! So, let’s see if I can give you some ideas about how you can put your writing back on the front burners and get cooking again (or writing, but you know what I mean!).

Build some awareness about your patterns with procrastination. When do you procrastinate? How, or in what way, do you procrastinate? Or maybe why? Understanding these questions will help you to put in place strategies that will reduce this pattern.

Feeling overwhelmed with your writing? Try breaking it down into smaller chunks. I am always reminded of the ancient Chinese philosophy of Lao Tzu “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Sure, I admit that sounds cheesy, but practically, taking smaller steps toward your writing goal is a good way to reduce those overwhelmed feelings and build a little momentum.

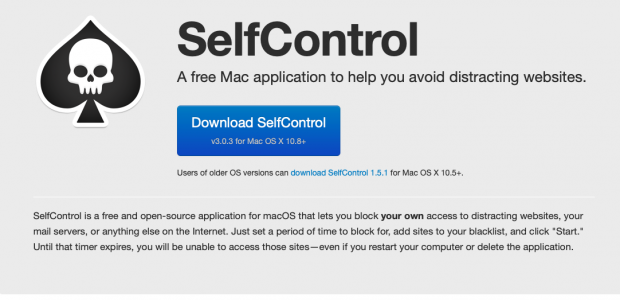

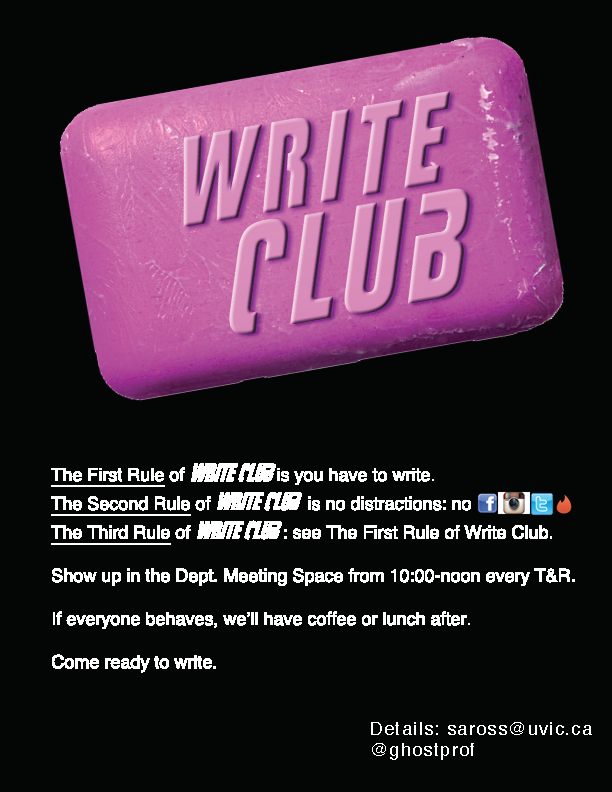

What about your environment? Is there a particular space that tends to support you staying focused and on task? Or do you try writing in spaces where there are lots of potential distractions? Knowing the kinds of distractions that curb your focus can also support you in creating a writing space that is beneficial to being productive.

Not sure exactly what or how you should be writing? It can be easy to procrastinate if we are not confident about what we need to do. Try taking a moment and explain to yourself what the purpose of your task is and what needs to be included in your writing. Next, ask yourself what aspect is confusing or unclear about your writing task and use that information think about the resources (i.e., supervisors, classmates, library supports, textbooks, etc.) that you can access that will help fill in some of your missing gaps and encourage you to regain your confidence with your writing task.

Hopefully, a few of these ideas will get your brain thinking. If you want to talk more, try booking an appointment for an individual consultation and explore personalized strategies to help you take back some control from the procrastination: https://uvic.mywconline.com/

Stress Management for Graduate Students

By Hannah

Stress is a fact of life. It is especially significant when one is a graduate student facing academic, professional, and personal challenges. Balancing academic rigors, professional demands, and personal life can be very challenging and stressful and if left unmanaged, it can disrupt life. What coping strategies can a graduate student use to keep stress at bay? Here are six strategies to start with.

- Assess your stress. Identify your sources of stress. Is your stress academic or non-academic? Being aware of your stressors is the first step to keep stress at bay.

- Find what works for you. Now that you have identified your stress, check what works for you. Does exercise help? A warm bath perhaps? A walk outside? Or meditation? Physical and mental activity such as mindful meditation is beneficial in combatting stress.

- Manage your time. Graduate studies is not just academics. It’s a delicate balance between academics and non-academic factors in your life. Master time management, stop procrastinating, take control of your calendar, and simply just do what needs to be done.

- Remind yourself of your long-term goal. Keeping track of your long-term goal help with motivation. Remind yourself why you are in graduate school and the opportunities you have received and will continue to receive in this journey.

- Celebrate small victories. A thousand miles always begin with one step. Your small victories are steps you take towards your long-term goal in graduate school and beyond. Celebrate them.

- Seek help. Various help services are available on campus. As graduate student, you have access to help services that will help you in when your academic journey becomes stress ridden.

References:

https://blogs.tntech.edu/graduate/2020/09/09/stress-management-for-students/

https://www.colorado.edu/today/2020/11/03/managing-stress-grad-student

https://gsm.ucdavis.edu/blog/5-tips-grad-school-stress

https://gsas.harvard.edu/student-life/harvard-resources/managing-stress

https://gradschool.duke.edu/student-life/health-and-wellbeing/tips-dealing-stress/

About Brodie

Brodie grew up in Ottawa, or the traditional unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishnaabeg people. As a certified teacher, he has worked with young people and families in a wide variety of contexts including outdoor experiential education, school-based support, substance use counselling, and inpatient mental health. If he is not working or studying, you can find him playing disc golf, and mostly likely, contemplating how he can apply SRL theory to improve his game (much to the chagrin of his disc golf partner!).

About Hannah

Hannah was born and raised in Surigao City, Philippines. She is currently in Victoria, working on her Master in Education International Cohort degree. She is passionate about teaching and has been teaching in a state college in the Philippines for 15 years. Her free time is spent with her family exploring and integrating in the Canadian way of life.