Welcome back. I hope you had a good break. We all needed a rest after an exhausting and challenging semester in the midst of a pandemic. Would you like to join me in starting 2021 with a resolution to exhume “zombie nouns” from your writing? In this humorous video, Helen Sword contends that when we turn other parts of speech (verbs, adjectives) into nouns by adding a suffix, we create “zombie nouns” or nominalizations that suck the life out of our writing, making it more abstract and difficult to read.

I’ll take Sword’s example: “The proliferation of nominalizations in a discursive formation may be an indication of a tendency towards pomposity and abstraction” contains seven nominalizations and doesn’t leave us with a clear idea of who is doing what. Several of the bolded words started as lively verbs (proliferate, form, indicate, tend) and others started as adjectives (pompous, abstract), but they life drained from each of them with the added suffixes, which added unnecessary complexity.

Reanimated, this sentence becomes “Writers who overload their sentences with nominalizations tend to sound pompous and abstract.” Note that a human (the writer) was added for clarity. So much better!

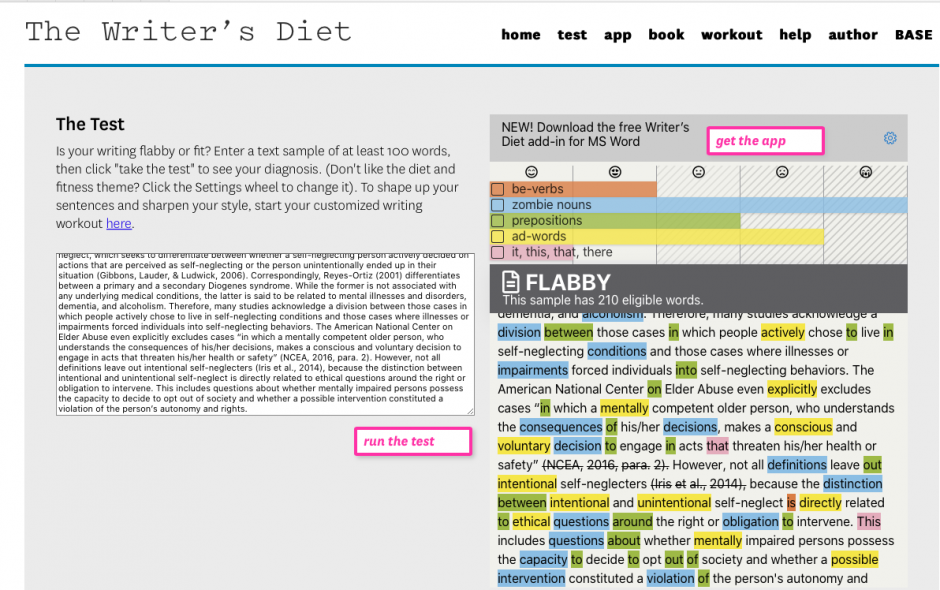

Sword also created The Writer’s Diet, a tool that measures words and constructions that weaken writing, for example be-verbs and zombie nouns. I tested a paragraph of a recently published article*, and zombie nouns were off the chart! Academics tend to use many nominalizations. Indeed, you may think of nominalizations as a required feature of formal writing, and perhaps you’ve even added nominalizations to make your writing sound more “academic.” But as Sword says, nominalizations obscure meaning, and you want to communicate important ideas and research as transparently as possible. I invite you to join me in analyzing your writing this year to see if you can enliven and clarify your sentences by reducing nominalizations.

Resources:

Sword’s tool and video are a good place to start. You can add the Writer’s Diet app to your Microsoft Word program for free. Another resource on this topic is OWL’s page on nominalizations.

Write for us!

Would you like to write for the blog? We welcome ideas and blog posts from graduate students, staff members, and instructors. Please send your query or post to Madeline Walker, Editor, at cacpc@uvic.ca

Before you write, please consider the following:

We love content relevant to academic communication (reading, writing, presenting) and graduate students. We value

-

- a unique point of view,

- posts reflecting the diversity of UVic students,

- stories that illustrate difficulties and vulnerabilities,

- posts with practical tips and ideas,

- fresh topics,

- humour,

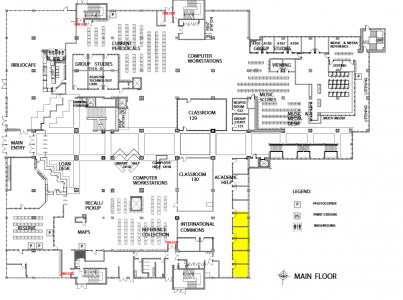

- content specific to UVic,

- and motivating and inspirational themes.

Posts should be between 250-750 words and may be edited for clarity, grammar, and punctuation.

If your post is accepted for publication, please provide a good-quality jpeg photo of yourself (not a selfie) and a short (2-3 sentence) biography.

* This is the recently published article where I obtained the excerpt: Nils Dahl, Alex Ross & Paul Ong (2020) Self-Neglect in Older Populations: A Description and Analysis of Current Approaches, Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32:6, 537-558, DOI: 10.1080/08959420.2018.1500858