By Luke Lavender

“How MUCH my life has changed, and yet how unchanged it has remained at

bottom!” – Kafka, Investigations of a Dog

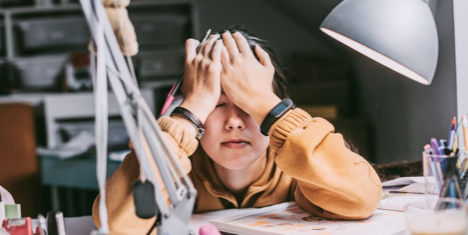

Clack go the keys; your mouse moves across the screen, in a lazy manner, hovering over the text you have managed to write and pour out. Your brain is weary, your eyes are adjusting—right, let’s see what we have managed to put into the world. Oh, no, what I am I saying here, how does Trump relate to this, am I really claiming THAT!? Wait, is that it? How did I get here, what was I saying, where was my writing going—is there no going back, I want to find what I was meaning to say before I lose myself in this cave.

Lost, lost, lost; our writing is screaming to say something, but it’s lost, I am lost in my writing. These feelings abound, as an undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate, as someone who simply is trying to speak to others. I’m sure we’ve all been here before, in that dark cave where what you are saying does not connect to what you mean, where you, your words and speech, are not in dialogue with your thinking, your intention—how does it happen, does it always have to be this way, can I not be myself in my writing?

It is not uncommon that we are told to avoid you, the subject of you, the subject of personal subjects in writing. As we ‘refine’ what we say, we find it common to try and escape ourselves in that process; we are told to write an argument, but make sure it is the argument that speaks, that you are not yourself in your text. In fact, in a certain way, is our writing not writing about avoiding that subject, the subject that we are? Sometimes, these lessons are personal and conscious—feedback asking us to not be so personal, to distance the writing from ourselves, to make sure that the writing speaks for itself—sadly, it is also an unconscious process; for many of us, writing operates through what Butler calls, in Excitable Speech, a “logic of censorship” that makes speaking, writing and dialogue, possible. Paradoxically, we are told to censor and write without ourselves, but why?

Formally the reasons abound, the father of them, is objectivity; “Academic writing should be objective… the language of academic writing should therefore be impersonal, and should not include personal pronouns, emotional language or informal speech”. For many this is all well and good, by eliminating use of the ‘I’ or yourself in the writing, we can escape bias, the tainted world of experience, and actually come into knowledge, true knowledge, knowledge that exists irrespective of a subject, a ‘you’, who does the thinking. Allegedly this leads to greater clarity, clearer reasoning, and more transparent writing; but does it? Is this all it does?

It seems sensible that objectivity removes us from what we say, so sensible that we miss the wider circle we find ourselves in: being objective requires being opaque to yourself in the writing, to not be reflective about what you think, let alone what you write. In this circle, we lose a grasp of the edges of our writing, it turns from being a cave into becoming a tomb; the writing becomes dark, you can’t find your way around it, let alone, get out of it—we find ourselves trapped into writing objectively and destined to find ourselves as mummified within hieroglyphics that we can’t even decipher. What a sad fate for objective knowledge, for objective writing, for an objective author; is this truly our destiny, can I not, myself, start understanding what I want to say? How, in a word, do we come to know the edges of ourselves, our writing, and what we are saying through writing itself? Should writing not be the means by which we not only illuminate our minds, but, fundamentally, learn about the thoughts that we have? Should writing not be about becoming aware of the thoughts we have and how to express them?

What could be a more perfect recipe for getting lost than the reflex to not be you in your writing, to write without yourself in the process? This is a concern that dogs the philosopher Raymond Geuss in the book “Philosophy and Real Politics”; the tendency of our philosophy, thinking, and, ultimately, writing is to lead us away from ourselves, to shut the doors on thinking about how your writing speaks to others, but also, reflects yourself. No wonder then, that, Mihaela Mihai calls for “responsible” and “responsive” theorising, a practice of being responsive to the realities of the world, and yourself in that world. Can we not take a stand and ask for a turn towards responsible and responsive writing? And what would it entail? A writing that, in its very existence, is reflexive, knows the edges of what it says, what it thinks, and what it thinks it says in contrast to what it actually says; a writing that is not entombed in objectivity, but open to itself. It is about making writing an exercise in reflection.

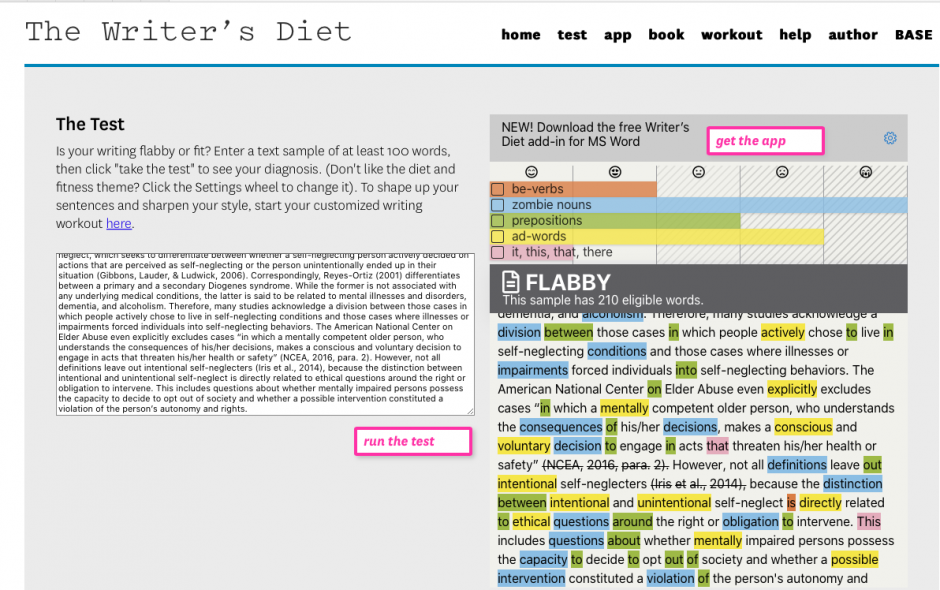

Are we not lost souls because we think our writing is transparent when it is actually opaque? Are we not in this cave because the way we are taught to write, academically, leads us away from being reflexive with what we say, and from knowing the limits of writing, from ourselves, on the page? So, as we turn to outside help, to others to help us say what we think and be transparent, perhaps we can try and recognise the vitality of being responsible and responsive as we write; in other words, of writing reflexively. This may happen in small steps, but perhaps we can collectively practice this lost language of ourselves in writing: journal, explore, and, above all, write about ourselves. We must play with our writing; so play, like I am in this very post, in this very writing. It doesn’t have to be objective, but it has to talk about you—give it a go with me, maybe we can find get out of the cave and find our paths together?

This first step—of turning writing into a reflexive exercise about reflecting on yourself, your thoughts, your limits—is exactly what we need if we want to know who we are and what we are saying when we put pen to paper, finger to key, and expose our writing-self to the world. So, let us not avoid the subject within writing, let us reflect on how to write reflexively. I for one, am tired of being lost in my own work.

Hey, I’m Luke, a masters student in Political Science with a Concentration in Cultural, Social, and Political Thought at the University of Victoria; I am working to work out what I am actually working on. I completed my undergraduate in the UK with a year abroad of study in Munich, Germany. Now, I find myself acting as the Teaching Assistant Consultant for Political Science, an International Teaching Consultant, and as a Graduate Student Tutor at the Centre for Academic Communication.