By Kaveh Tagharobi

Having a full time job and writing a thesis is not easy. Actually, this is an understatement because sometimes the task appears utterly impossible. Work projects alone require your undivided attention, and at the end of the day, there is not much intellectual power left to read about your topic, organize your thoughts, and more importantly, to weave those thoughts into the paragraphs, sections, and chapters of a thesis. The most important factor in writing a thesis is consistency, and having a full-time job, and (occasionally) a life, makes it too hard to maintain that consistency. You might manage to make a  breakthrough on a weekend or during “holidays,” but as soon as you spend a whole week on the work roller coaster, you find yourself back at square one, detached from your thesis, needing to review stuff that is now weeks old.

breakthrough on a weekend or during “holidays,” but as soon as you spend a whole week on the work roller coaster, you find yourself back at square one, detached from your thesis, needing to review stuff that is now weeks old.

This is where I kept finding myself for two years trying to finish my MA thesis while working at the CAC. As an EAL Specialist, I knew in theory how to go through the writing process and how to break down writing tasks into smaller chunks in order to make incremental progress. I did not, however, find the place, time, or the motivation to put what I knew into practice.

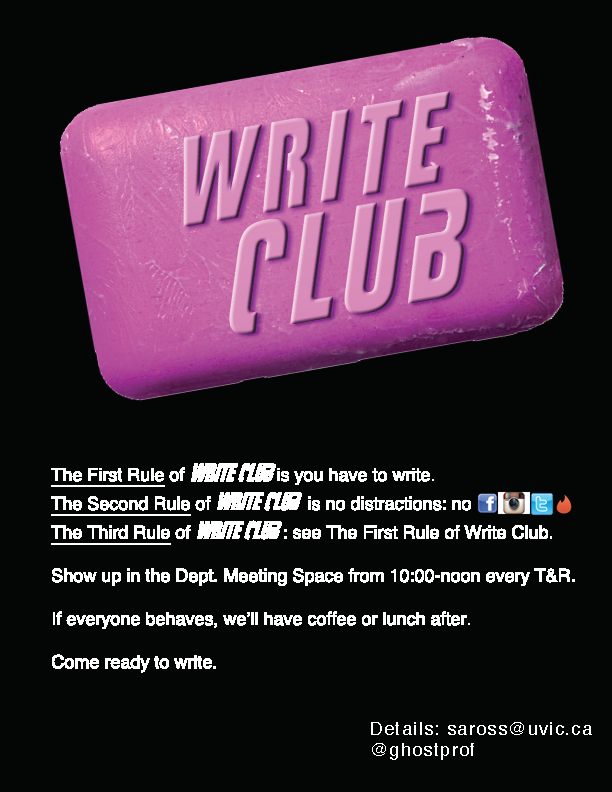

But things changed in the summer of 2016, when I started to go to Write Club, a group writing initiative started by Stephen Ross in the English Department for faculty and graduate students to write together. The ad for Write Club described it as “a no-pressure, no distraction setting for getting that pesky writing done,” and it encouraged bringing any writing project because “No one cares what you write, so long as you write.” This simple, crisp, and forthright invitation was all I needed to start building a simple, crisp, and forthright habit: to carve two hours out of my workday (by going to work a couple hours earlier) and writing about four paragraphs during that time. It was as simple as that, and I wrote my thesis (the whole 50,000 words) in the same rhythm, two hours a day, four paragraphs at a time. Of course, on some days, I spent my two hours reading, planning, and revising, but I tried to keep the same habit rain or shine. In the fall, when I got busier at work and could not go to Write Club regularly, I still kept my two hour routine early in the morning or after work in the evening. It was surprisingly easier to keep the momentum once I got into a groove, and I actually worked for much more than two hours during Christmas holidays and as I got closer to the finish line. Write Club helped me finish my thesis, and as someone who had tried to start writing groups at the CAC as part of my role, I went back to Stephen to ask him about the reasons for Write Club’s success.

My main question for Stephen was how he managed to spark interest and keep people going to Write Club. I had tried to do the same, and I had noticed that the initial enthusiasm would dissipate rather soon. He reassured me that it is part of the nature of such initiatives to “bloom and fade” somewhat quickly, and that it is fine. To increase persistence, Stephen believed that you should “go slow burn”: “You don’t need to go for huge numbers to make a big show and a big deal out of it.” This was true. It was somehow the simplicity of the idea that attracted me and kept me going. He said that it was just him in the beginning and then he decided to send out an invitation to faculty and graduate students. “I never advertised it outside English or to undergraduates.” This allowed him to keep it easy and simple, and that helped with consistency.

One other way to keep it simple was to limit the activities and functions of the group. The invitation simply said “come and write.” I asked if there was any sharing of writing or plans to give feedback. “Very informally,” Stephen said. “Once Adrienne [Dr. Adrienne Williams Boyarin, an Associate professor in English] had a question about her paper, and we made her deliver her paper. It became a discussion.” But it seemed that for the most part, Write Club was just about being there and quietly beavering away. “The emphasis was on not disturbing other people. I did not want anybody to hijack the session,” said Stephen. I agreed. The idea was to provide encouragement and motivation by showing that we are all in it together. I remember being there, and as I got tired, I would look at others writing and would feel that I was not alone, and that helped me continue. Stephen confirmed this: “It is somehow like physical education. You need a workout partner. For writing, it is kind of the same principle.” They key is to know that someone is doing the same thing you are doing. He thinks that you do not even have to be in the same room to do this. You can have a “writing appointment” with someone and write at the same time. “Not everybody likes to write around other people. It is weird for them, and that’s fine. For me it is all about accountability.” He continued with his delightful frankness, “Like many academics, I am driven by shame. If I create conditions for myself, I don’t want to embarrass myself.” I definitely felt that sense of accountability. Knowing that other members would show up to the writing session every morning gave me not only the motivation to commit to my writing, but also a sense of being watched by kind, yet panoptic co-writers, and this kept me leaving home a couple hours earlier every day even when I really didn’t feel like it.

It is not all about being kept in check though. “Equally it is about support,” Stephen said. “We are all suffering. Writing is not easy for anyone. Anyone who tells you it is easy, then they are not writing good stuff!” He was also straightforward in admitting the hardships: “some days were just so terrible, and I wanted the students to know that.” He showed it as a way of “modelling” for student participants because he thinks we must accept that blocks are part of writing. Yet there are solutions. He thinks that taking a break and coming back later can work, as “the brain cooks up the solution” when you go about your day doing other stuff. “Go have lunch or go for a walk and think about something else. At some point, you will have an ‘aha moment.’ Create space for those.”

Creativity and productivity come with a healthy balance: “Write for three hours a day max, and then do other things. The window of productivity is relatively tiny.” This makes Write Club perfect because in those two hours “you can prime the pump.” Longer periods of work “lead to frustration. Because you are working too hard. Not smart. You shouldn’t be writing for more than three hours per day. You do that, and your brain quality and quantity falls down.” Stephen said that he wrote a book and several journal articles during the summer with the same routine of 2-3 hours per day, and he still managed to lead a normal life: “I pick up my kid from school, go for a run, etc., and if I have an idea while doing these, I would dictate it into my phone for later.” I think this is clever, healthy, and reasonable, and he agrees: “this is actually the kind of life an academic should lead.”

I thank Stephen for his time and leave his office, with a little bit more hope and motivation for my future academic writing projects. The power of group writing is immense, and Write Club proved that by helping me and others accomplish important writing projects. I hope there are more programs like this across the campus to help graduate students get their writing done. Maybe all we need is an uncomplicated plan and a healthy balance of accountability and support.

Kaveh Tagharobi is an EAL (English as an additional language) Specialist at the Centre for Academic Communication. He is also in the English Department’s MA Program with a concentration in Cultural, Social, and Political Thought.