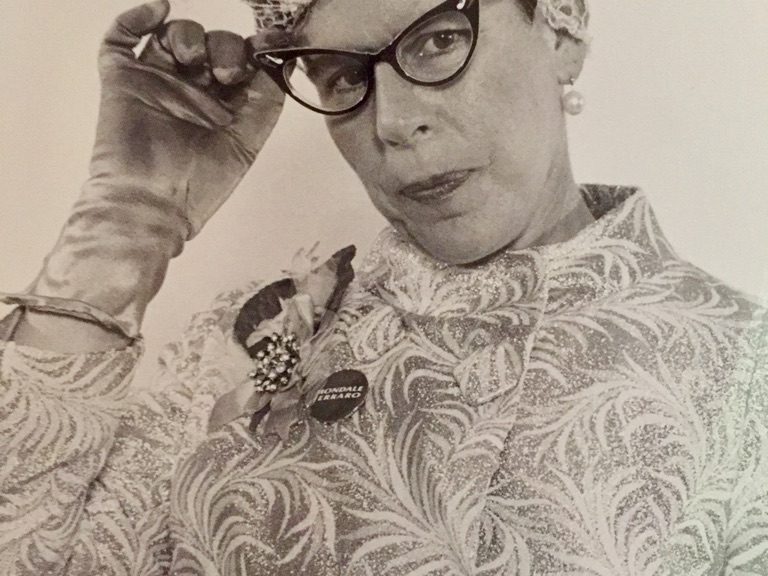

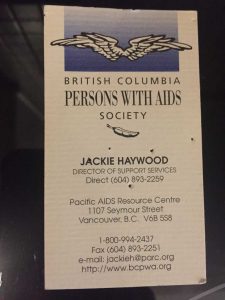

By: Jackie Haywood, Interviewee, Planning Committee Member & Gallery Curator

Cocooned in the Vancouver East Cultural Centre theatre during the rehearsal of ‘In My Day’, the dark walls and lush curtains hold witness to bold and cathartic words. For me it feels like part of a journey from fear and loss to witness and honour.

As a forty-something Commercial Drive lesbian I walked in the door of a fledgling AIDS organization being birthed by a handful of white gay men from many walks of life, levels of education, upbringing and individual acceptance of their sexual preferences. It was 1987. I was working a gentle mullet cut with a tail. I had heard there was a job in the ‘Davie Village.’

I did not have one close gay male friend. I was acquainted with a small cadre of alternative, soft East Van gay men who co-existed with lesbians on The Drive. Men trying to grapple with feminism supplied child care for women’s events, supplied sperm for kitchen table fertilization and marched ardently behind the women during ‘Take Back the Night’ demonstrations.

Impressed by my typing-test results and years of women’s advocacy, feminist activism and rag tag training in civil disobedience, I was hired at Vancouver Persons With AIDS Coalition (VPWA) by Warren, Benoit and Kevin. I joined a village within a village. I did not look back. I was clever, kind and community connected. I organized and empathized while writing hard-hitting letters. I could stand my ground. A sense of humour was at times my kryptonite. I had a sass-back patience with bestie gays wanting to redecorate my living room or add more cleavage to my wardrobe. It was a good fit.

I learned way too much about gay sex whether it was the endless cruising or out-there safe sex questions I was asked in all seriousness. Maybe it was the leather party fundraisers or the x-rated drag queen repartee. A smart young hustler working out of ‘Boys Town’ smirkingly displayed his Prince Albert piercing to me while I was typing away at my desk. I knew then my life here would never be boring.

I learned way too much about gay sex whether it was the endless cruising or out-there safe sex questions I was asked in all seriousness. Maybe it was the leather party fundraisers or the x-rated drag queen repartee. A smart young hustler working out of ‘Boys Town’ smirkingly displayed his Prince Albert piercing to me while I was typing away at my desk. I knew then my life here would never be boring.

Oh, the stories, the fear, the laughter, the membership list that grew and grew. Mothers, sisters, never fathers, sat with me, asked questions, disbelieved facts, judged and hid their sons away from family friends. One family forbade their son from coming home for Christmas because his sister would be there with her newborn.

‘Final Exit’, by the Hemlock Society, published in 1991, was discretely handed around the office like a secret treasure map. Men who could not bear the loss of mobility, the dementia, deep purple facial lesions, or fear of being labeled homosexual, died by their own hand, often with the help of underground medical assist and brave friends.

I knew the colourful, high-energy actor who, according to in-the-know reports, jumped from his balcony in the West End. I vividly recall the shy young man, almost a boy, from the Maritimes who repeatedly tried to give me his small Sheltie dog. He died from a prearranged combo of medications within days of asking me to yet again take his dog. They were young. I have their photos.

So much sorrow to remember. So many to remember. “Pneumonia”, said parents. “Cancer”, read obits. “Fucking AIDS!”, said friends.

The stories do not end with my memories. They continue. Now, thankfully there is an Oral History Archive, ‘HIV In My Day’, capturing over a hundred peer interviews of HIV/AIDS long-timers, the experiences of caregivers and activists.

We will remember, we will learn from these dark times, experience the truths, fears and the power of a common-thread community from these shared stories. If we listen closely, the cruel hopelessness of the time is off-set by the will to fight and survive.

Through the Oral History Project interviews, we hear personalized experiences of marginalized communities. People who, due to the stigma and fear of being identified as gay, did not walk through the doors of early AIDS organizations.

HIV positive women’s voices tell us of years of medical misdiagnosis and the suffering and tragedy that resulted. Women, whose male sexual partners lived a secret parallel life. speak out in interviews. Many are angry. Many were blindsided. Their stories include barriers to alliance with early HIV/AIDS gay community and not taken seriously by the medical establishment of the time.

I value my ongoing work with the dynamic ‘HIV In My Day’ Oral History team as an interviewer, interviewee, writer, creative support and an HIV negative long-term survivor of this turbulent, unthinkable time. We must learn these stories, hear these voices.

Now there is a play! ‘In My Day’, a verbatim play crafted with words from the Oral History Archive will be mounted at the Cultch in December 2022. The script is composed verbatim from a quilt of diverse voices of the living, their memories and life experiences.

The play is written by one of our interviewees, playwright Rick Waines. I worked with Rick in the early years at VPWA as he became involved in organizing, protesting, leading and sharing his unique story to students and teachers.

I sit in awe in the energized theatre, watching actors passionately lift these voices, their characters expressing pain, fear and pleasure. Stories of senseless loss and hard-fought survival are raw and raucous. Dark humour, rage and protest cry out in front of us. “Act Up. Fight AIDS”!

Being in the audience fills me with gratitude for this play. I hear familiar stories. I feel my head silently nodding, ‘Yes, I remember.’ Some lines make me laugh, others cause me to wipe away slow tears. I hear words from my own interview. It feels like a line of emotional dominos falling.

I see the faces of those who died upon the faces of the actors who speak their words. There are spirits in this theatre. For me it’s chilling. It’s respectful. It acknowledges those that held a front line to government and pharmaceutical giants and those that recoiled in fear.

A familiar discomfort surfaces. The hard reality that I’m sitting here alive and aging well while multiple hundreds of men and women I knew have died. We are the living, the rememberers.

I visualize an old but healthy tree standing in a forest that’s lasted through a cruel, blazing destructive fire. My day, years, decades of living during the AIDS times have come full circle in this intimate theatre surrounded by artists, academics, activists and young dreamers of a future rising from a past that burns for many of us.