Is it Different for Women? Gender Differences in Romantic Relationship Functioning for Young Adults with ADHD

Although research has begun to acknowledge the role of ADHD in social dysfunction, gender differences do not tend to receive sufficient attention. Research increasingly suggests that women present with an altered set of ADHD symptoms, increased mental health concerns, and report greater impairment in many domains, including their romantic relationships. It has been suggested that ADHD symptoms are uniquely problematic for women because ADHD-related behaviors (e.g., disorganization, impulsivity) are incongruent with expectations for female behaviour (i.e., to be tidy, polite, and social).

Our Focus

- to investigate how gender differences in ADHD symptoms impact relationship functioning;

- analyze the roles of stress and anxiety in this association; and

- test whether conflict with gender expectations contributes to interpersonal difficulties for young women with ADHD.

Methods

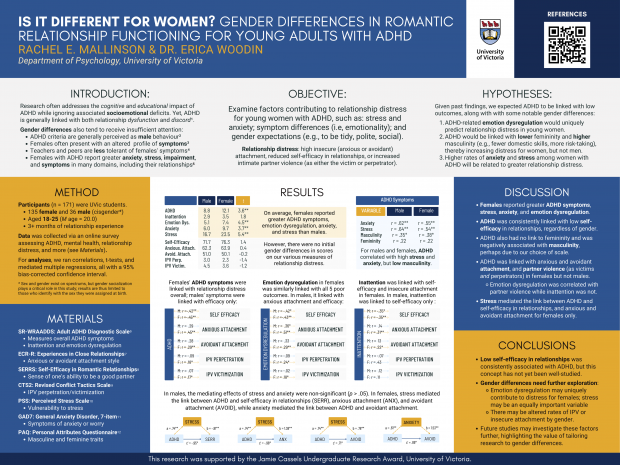

- 171 undergraduate students (36 males and 135 females), aged 18-25 years

- Online self-report survey assessing: ADHD symptomatology, anxiety, stress, gendered attributes, and relationship distress (i.e., insecure attachment style, intimate partner violence).

Results

More ADHD symptoms were correlated with more stress and anxiety, and less relationship efficacy* in both males and females.

In women only, ADHD symptoms were also linked with attachment-related anxiety** and  avoidance***

avoidance***

Stress helped explain the link between ADHD symptoms, relationship efficacy, & attachment anxiety and avoidance, so vulnerability to stress could be an important dimension of interpersonal difficulty for women with ADHD.

Females’ ADHD symptoms were additionally linked with increased perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence, but stress did not help explain these links.

Contrary to expectations, more ADHD symptoms was correlated with less masculinity and was unrelated to femininity.

Nonetheless, the rest of our results suggest that there is a highly complex association between gender and relationship distress for individuals with ADHD, lending support to the importance of tailoring information and interventions to the separate needs of men and women.

*This refers to perceived ability to successfully navigate and maintain healthy relationships; someone with low relationship efficacy may struggle to communicate effectively, set boundaries, resolve conflicts, or trust others, for example.

**Attachment-related anxiety is characterized by a fear of abandonment and a tendency to seek constant reassurance from partners.

***Attachment-related avoidance is characterized by a fear of intimacy, emotional distance, and a tendency to prioritize independence over closeness in relationships.

See Rachel’s poster presented at the 2023 JCURA fair!

References

- Wymbs, B. T., Canu, W. H., Sacchetti, G. M., & Ranson, L. M. (2021). Adult ADHD and

romantic relationships: What we know and what we can do to help. Journal of Marital

and Family Therapy, 47(3), 664-681. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12475 - Ohan, J. L., & Johnston, C. (2005). Gender appropriateness of symptom criteria for

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, and conduct

disorder. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 35(4), 359–381.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-005-2694-y - Hinshaw, S. P., Nguyen, P. T., O’Grady, S. M., & Rosenthal, E. A. (2022). Annual

research review: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women:

Underrepresentation, longitudinal processes, and key directions. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(4), 484-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13480 - Mowlem, F., Agnew-Blais, J., Taylor, E., & Asherson, P. (2019). Do different factors

influence whether girls versus boys meet ADHD diagnostic criteria? Sex differences

among children with high ADHD symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 272, 765-773.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.128 - Fedele, D. A., Lefler, E. K., Hartung, C. M., & Canu, W. H. (2012). Sex Differences in

the Manifestation of ADHD in Emerging Adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(2),

109-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710374596 - Marchant, B. K., Reimherr, F. W., Wender, P. H., & Gift, T. E. (2015). Psychometric

properties of the Self-Report Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder

Scale. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 27(4), 267–282. - Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item-response theory analysis

of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 78, 350-365. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350 - Riggio, H. R., Weiser, D., Valenzuela, A., Lui, P., Montes, R., & Heuer, J. (2011). Initial

validation of a measure of self-efficacy in romantic relationships. Personality and

Individual Differences, 51(5), 601-606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.026 - Chapman, H., & Gillespie, S. M. (2019). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): A

review of the properties, reliability, and validity of the CTS2 as a measure of partner

abuse in community and clinical samples. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 44, 27-35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.10.006 - Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R., & Cohen, S. (1983). A global measure of perceived

stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385-396.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 - Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Lowe, B. (2006). A brief measure for

assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 - Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Stapp, J. (1975). Ratings of self and peers on sex role

attributes and their relations to self-esteem and conceptions of masculinity and

femininity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076857