Why are people involved in sex work more likely to use “hard” drugs such as cocaine and heroin than someone working as a server in a restaurant? Is it because they are “immoral” or “bad” people, or is it because their occupation is more stigmatized? If our society directed less stigma or judgment toward this group, would there be less use of hard drugs and smaller differences in substance use between sex workers and servers? Our research seems to indicate yes.

Stigma, which involves the use of defamatory labels and discriminatory actions by individuals and social institutions, is directly linked with poor physical and mental health outcomes for people who perceive that they have been stigmatized. Drug use can also be a way to cope with stigma.

Some people working in the sex industry use drugs to cope with the negative self-image and social isolation engendered by occupational stigmas, or to self-medicate in the presence of physical, mental, or emotional health challenges. The use of these “hard” drugs is also socially less acceptable, making it an additional source of stigma for the individuals using them.

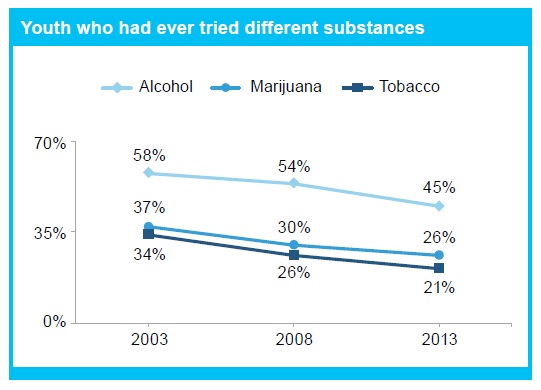

We investigated the link between perceived stigma and substance use with interview and survey data from a study of three service work occupations: sex work, food and beverage serving, and hair styling and barbering. We found1 that workers from all three of these occupations reported negative societal perceptions of their jobs and experienced stigma in their interactions with the public and with health care professionals. However, perceived stigma was significantly more common and more intense for people working in the sex industry, and a larger number of these workers told us that they had come to accept perceptions that their work was disreputable. Most importantly, a high level of perceived stigma was associated with a higher level of use of “hard drugs”. Interestingly, we found that stigma did not influence the use of “softer” substances such as alcohol or marijuana.

Perceived stigma is an important factor that helps us understand differences in substance use. It is no coincidence that the occupation in our study most associated with hard drug use was also the occupation most frequently associated with immorality and criminality.

So, how do we work to reduce the stigma associated with sex work? One way is by including people with lived experience when shaping policy that affects the sex industry. Their voices and insights will be essential for designing harm reduction strategies that challenge prostitution laws and other policies that keep people working in the sex industry disciplined, controlled and excluded, and that contribute to a powerful stigma that encourages the use of addictive substances.

1Benoit, C., McCarthy, B. & Jansson, M. (In press). Stigma, service work, and substance use: A two-city, two-country comparative analysis. Sociology of Health & Illness.

Authors: Dr.Cecilia Benoit, Scientist, Centre for Addictions Research of BC; Dr. Mikael Jansson, Scientist, Centre for Addictions Research of BC; Bill McCarthy, Chair, Department of Sociology, UC Davis.

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC