Part 2 of our new “Cannabis and Driving” blog series.

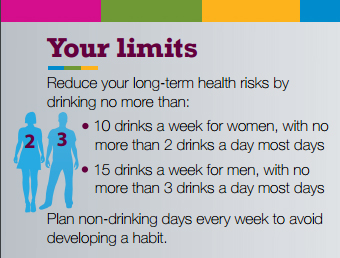

In my last post, I noted the existing penalties for drinking and driving with both federal laws (driving with blood alcohol content (BAC) at 0.08%) and provincial laws (driving at 0.05% alcohol, 0.04% for Saskatchewan). Here, I review some major research issues with creating these laws and provide an assessment of their effectiveness. This process will be useful for contrasting our knowledge of alcohol with cannabis.

What biological specimens are valid?

There is strong agreement among experts that blood tests are the best biological sample for detection to identify concentration levels that may be associated with impairment for alcohol and all other drugs; however, drawing blood requires specialized training, is invasive, and the blood needs to be analysed by offsite laboratories. In order to accept the current portable breath test as evidentiary in courts, numerous scientific studies have been conducted that demonstrate portable breath test findings are highly correlated with blood tests. This correlation is acceptable but not perfect. Breathalyzers in North America are calibrated to produce lower BACs in order to compensate for imprecision.

Central to practically all impaired-driving laws in Canada is the ability to detect BAC levels with breath tests. The breathalyzer is less invasive than a blood test and non-professional staff can obtain results quickly. Although the breathalyzer is not perfectly accurate to detect alcohol concentrations, it is an excellent substitute.

As well, alcohol is water soluble, meaning that the proportion of alcohol in the blood is a very good indicator of the amount of alcohol affecting the brain.

At what rate is alcohol eliminated from the body?

According to forensic toxicologists, the elimination rate of ethanol for an average individual is about 0.015% absolute alcohol per hour with a range between 0.01% and 0.02% – between one half and one standard Canadian drink per hour. This rate of elimination is fairly constant over time. Since alcohol is eliminated in a fairly constant rate, a reasonable estimate can be made of a person’s BAC at an earlier time.

What is the relationship between BAC levels and human performance?

To fully understand the nature of the relationship between BAC levels and human performance, findings from three types of studies are needed: laboratory, observational and validity studies. Each type of study has strengths and weaknesses. Laboratory studies are those conducted in controlled settings where subjects are administered alcohol and performance changes are measured from before to after drinking. These studies are excellent for detecting the influence of alcohol on performance; however, we cannot say whether any effects will translate into safety risks in real world situations. For example, small performance deficits can be detected in these laboratory studies that have no effect in the real world, or possibly those experiencing these effects may be unlikely to engage in potentially dangerous activities. Observational studies are those of real life situations where those in accidents (or responsible for accidents) are compared with those not in accidents (or not responsible for accidents) in terms of the proportions with various BACs. Finally, if both these types of studies show relationships between BAC level and performance deficits, then validity studies are needed to demonstrate the degree of accuracy of BAC cut-offs in relation to performance deficits. If all three of these types of studies provide similar conclusions, evaluation studies can then assess the effectiveness of interventions to detect driver BACs.

Laboratory studies –These studies have shown that the acute effects of alcohol negatively affect performance in a dose-response relationship. A 2000 review prepared for the U.S. Department of Transportation looked at over 110 studies in a 15-year period and concluded that alcohol affects different performance skills at different BAC levels. In these studies, both BAC levels and performance for each individual was measured and comparisons between the two made. The majority of subjects had impairments at 0.05% alcohol and practically all subjects (about 95%) experienced performance deficits at BACs of 0.08% alcohol. Performance deficits increase with higher BACs.

Observational studies – A literature review conducted for the Canada Traffic Injury Research Foundation looked at several large observational studies comparing the BAC levels of drivers in crashes with those not in crashes and found a very strong relation between BAC levels and the likelihood of collisions. The most recent high quality, large scale case-control study compared the crash risk of drivers at several BAC levels with a BAC of 0 and found the likelihood of crashed increased in a dose-response manner: 1.4 (BAC=0.05%), 2.7 (0.08%), 7.6 (0.15%), and 18.8 (0.20%). These levels of risk increase further when one includes covariates and estimates of BACs among missing drivers in crashes due to hit and runs.

Validity studies – Research shows the breathalyzer is an excellent diagnostic tool for assessing alcohol related impairment at higher levels of 0.08% alcohol, as trained observers can identify those under this condition.

Do evaluation studies demonstrate legal interventions are effective?

Studies have also been conducted on the impact of per se laws in relation to alcohol-related crashes. These laws are based on the theory of deterrence: that people will refrain from committing actions based on the certainty, swiftness, and severity of consequences. The majority of these evaluations show new or lowered legal limits have some beneficial effect on traffic safety measures, such as alcohol related collisions, although in some cases these effects were temporary. Both certainty and swiftness of punishment are more important components of successful programs than the severity. Some provinces have implemented effective legislation that increases the certainty and swiftness of punishments. For example, we found that BC’s Immediate Roadside Prohibition program, where driver’s licenses can immediately be suspended for three days for those with a BAC level between 0.05% and 0.08% alcohol, was effective in reducing three types of alcohol-related collisions over a two-year period.

Conclusion

Considerable research on the breathalyzer for alcohol shows that it is an accurate measure of BACs which are closely related to performance deficits, and convenient to administer. Laboratory, observational and validity studies all show major performance deficits for individuals with BACs of 0.05% or 0.08% alcohol or higher. As well, evaluation studies of the implementation of per se laws at these cut-offs have found beneficial effects. To summarize, there is a strong scientific base for supporting both Federal and provincial laws against drinking and driving.

Part 1: Proposed federal legislation on cannabis and alcohol impaired driving

Part 3: The safety benefits of THC blood testing: a research summary

Part 4: The myth and origins of 24-hour performance deficits from cannabis

Scott Macdonald is the Assistant Director of research at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and a professor in the School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria. He has been an expert witness in several cases related to drug testing in the workplace. Material from this series is taken from his book, Cannabis Crashes: Myths and Truths, Lulu Press.

Scott Macdonald is the Assistant Director of research at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and a professor in the School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria. He has been an expert witness in several cases related to drug testing in the workplace. Material from this series is taken from his book, Cannabis Crashes: Myths and Truths, Lulu Press.

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.