As returning students head back to campus and new students set foot on campus for the very first time, one thing we can all count on is that this is a time we’re looking to make new friends and solidify old bonds. While not all students like to party, and even fewer use drugs when they party, some do. It’s important for students to consider the risks of using substances these days, when fentanyl has become part of our drug supply.

As returning students head back to campus and new students set foot on campus for the very first time, one thing we can all count on is that this is a time we’re looking to make new friends and solidify old bonds. While not all students like to party, and even fewer use drugs when they party, some do. It’s important for students to consider the risks of using substances these days, when fentanyl has become part of our drug supply.

First of all, what is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is one of a class of drugs called “opioids”, drugs that bind to receptors in our brain and alter our perceptions of pain. There are many different opioids, including prescription drugs like Tylenol 3, OxyContin, and Percocet. When prescribed, they are often used after surgery or for moderate-to-severe pain treatment.

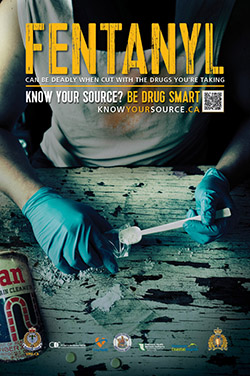

Some opioids that are available by prescription or used in hospitals are also manufactured in illicit labs, or “kitchens”. These drugs can be made to look like prescription drugs, and can also be sold as, or show up in, party drugs, like cocaine or MDMA.

Different opioids also have different potencies (strengths). It has been reported that fentanyl is 100 times stronger than hospital-grade morphine. And the even newer carfentanil is said to be 100 times stronger than fentanyl.

What’s important for students to know (when it comes to fentanyl and other opioids)?

The real challenge with the drugs that students are using at parties is that they’re part of an uncontrolled supply chain. When drugs are manufactured and obtained outside of a regulated system, it’s impossible to be sure about the contents of the drug and amount they’re taking.

When people can trust what they’re taking, they can better manage their risk. Like alcohol. This is important to remember because fentanyl is often not the drug the person is intending to take. Many people who have overdosed believed they were taking MDMA, cocaine, another type of opioid or something else altogether—but the substance contained some fentanyl.

Haven’t we already talked about this enough?

Open conversations create trust, reduce fear, and make it possible for us to learn from one another.

Engaging in thoughtful, open-ended conversation helps us to develop the skills to assess risk, think critically, and make better decisions. Once we’ve considered something carefully we’re a lot less likely to act out of impulse, habit, or in response to influences like peer pressure.

And we can apply these takeaways to other aspects of life—like how to help a friend going through a rough patch, recognize the signs of overdose, respond in a crisis, and how to be true to ourselves. But we need to take care not to lecture.

Is there anything we can really do to prevent overdosing?

Understanding the risks and how to mitigate them can go a long way!

Risk is central to our growth and development, and we often embrace ones with the potential for reward because the pay-off helps us lead fulfilling lives.

Ever tried or considered rock climbing? In order to get the most out of it, you would take time to identify safe practices that mitigate the risk, such as bringing a buddy and testing the quality of your harness.

Many of us think that the opioid overdose crisis only affects people who use drugs regularly, or have an addiction. But even a single occasion that (accidentally) involves fentanyl can lead to overdose.

So it makes sense to use the same care and thoughtfulness when going to a party where you and your friends will likely encounter new opportunities, and risks.

What do you suggest then?

You can still have a good time out, while managing your risk! A few tips to keep in mind:

- It’s safest to only party with friends or people you trust (i.e., use in a safe environment).

- If you are using a drug in a group, it can be useful for one person to try the drug first. You can also “test it before you ingest it” using these fentanyl test strips.

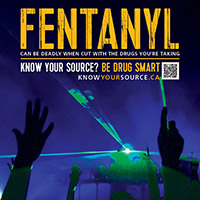

- Know your source (but remember there are no truly safe sources for uncontrolled substances!).

- Stick to one substance and pace yourself so you don’t get in over your head (you can always do more, but you can never do less).

- Avoid mixing alcohol with other drugs, as they can interact in unpredictable ways. You can also learn more about how different drugs can interact using this drug combination chart.

- If you or someone you know does overdose, it helps to know the signs and symptoms of overdose and how to respond. Most campuses now offer overdose training and naloxone kits.

- If you find yourself using more often, it might be time to ask yourself why—are you using substances to cope with life or maybe feeling pressured by others?

Catriona Remocker, Campus Projects Consultant, Systems View Consulting

Tanya Miller, Provincial Coordinator, Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses

Kristina Jenei, Research Assistant, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, Opioid Dialogues