Teens sometimes get a bad rap for being careless with their bodies and minds. But according to McCreary Centre Society’s 2013 Adolescent Health Survey, published in February 2014, most of the 30,000 BC youth surveyed say they are healthy or very healthy (87 percent), and 8 out of 10 report good or excellent mental health (81 percent). The majority also said they feel cared for, competent and confident about their future.

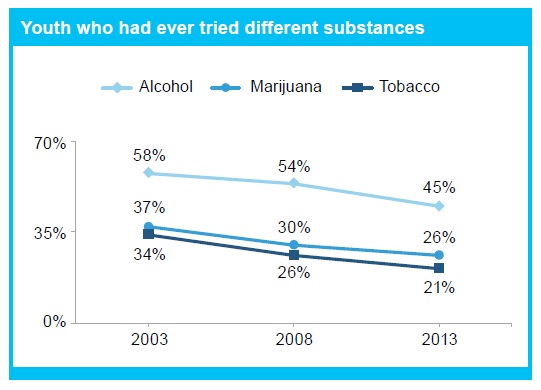

Along with feeling good about themselves and their world, more young people are steering clear of alcohol and other drugs. Survey results show substance use rates have been declining over the last 10 years, and the majority of students in Grades 7 through 12 say they have never experimented with alcohol, cannabis (marijuana) or tobacco.

Part of what’s driving this decline is that young people are waiting longer before trying drugs. For example, 35 percent of young people who have ever tried alcohol waited until they were 15 or older (compared to only 20 percent in 2003), and of those who have ever tried cannabis, 41 percent waited until they were 15 or older (compared to 28 percent in 2003).

Equally positive, youth who are choosing to use alcohol or other drugs seem to be taking fewer risks. For example, 2 percent of those who had ever used alcohol said they had driven after drinking in the past month, down from 6 percent in 2008 and 8 percent in 2003. There was also a decrease in impaired driving among youth who had ever used cannabis, although 9 percent had done so in the past month.

So, why are BC youth making healthier choices? A number of protective factors seem to be at play including family connectedness. For instance, youth who felt their family paid attention to them were less likely to drive after drinking than those who did not experience such attention (2 percent vs. 6 percent). They were also less likely to have been a passenger in a vehicle with someone who had been drinking (15 percent vs. 33 percent).

Having someone to confide in seems to make a difference too. Students with supportive adults in their lives are less likely to have used alcohol (43 percent vs. 54 percent). And, among students who had tried alcohol, those with an adult they could turn to were less likely to report binge drinking in the past month (37 percent vs. 42 percent). Youth in government care who had a supportive teacher or other caring adult in their lives were also less likely to binge drink in the past month.

What exactly does this mean for parents, teachers and other caring adults in young peoples’ lives? Many teens are making healthy and positive decisions and we can continue to support and acknowledge the positive decisions they are making. For teens who are struggling to maintain their health or happiness, we can make a difference by reaching out to them. Finally, we must continue leading by example. By being happy and healthy adults, we show young people that health itself is a worthy life-long goal.

For more information about the results from the 2013 BC Adolescent Health Survey: http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/From_Hastings_Street_To_Haida_Gwaii.pdf

Author: Nicole Bodner, Centre for Addictions Research of BC

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC