I have had the privilege to work with various peer-run organizations of people who use drugs for many years now. As a National Programs Manager at the Canadian AIDS Society (CAS), every harm reduction related project I work on first starts with creating a countrywide steering committee that includes people with lived experience of drug use to guide the project and ensure its relevance. Not having much guidance on how to properly include people with lived experience as part of decision-making, I navigated my way by trial and error. At times, I tripped over my own assumptions and clumsily had to adjust my process on the fly. The people I worked with also shared their experiences about participation in other committees, which had been at times positive, and other times negative or tokenistic. I became intrigued about finding out how to better include people with lived experience on such committees.

I decided to make this subject the focus of my PhD studies, under an amazing supervisory committee, Dr. Bernie Pauly, Dr. Cecilia Benoit and Dr. Budd Hall, and in partnership with the Drug Users Advocacy League (DUAL) in Ottawa, Ontario, and the Society of Living Illicit Drug Users (SOLID) in Victoria, British Columbia.

Now, we are so thrilled to be launching the fruits of our labour, From One Ally to Another: Practice Guidelines to Better Include People who Use Drugs at your Decision-making Tables, as part of the Centre for Addictions Research of BC’s (CARBC) Bulletin series.

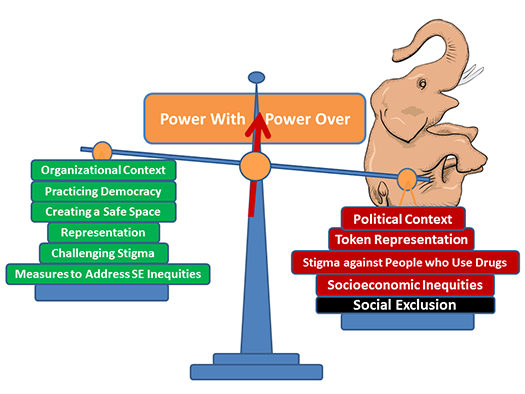

Inclusion of individuals and groups marginalized by the stigma against drug use in decision-making structures has emerged as a way to challenge the dominant power structures. The goal is to render decision-making more equitable for groups that have historically been excluded from decisions that affect their lives. The premise is that by including people experiencing marginalization at decision-making tables, power will be shared and shifted from power over to power with people with lived experience. By sitting together around at decision-making tables, the possibility opens up for a shift in consciousness whereby people learn to relate to each other in non-stigmatizing, non-discriminatory ways. Research on the processes and outcomes of such inclusion, however, has been sparse.

Often over coffee with various people who use drugs, we discussed how interesting it would be to better understand the relational dynamics at play at decision-making tables and the factors that either contribute to or hinder the transformation of power inequities. These groups of people who use drugs longed for practice guidelines to hand over to organizations that wanted experiential people at decision-making tables.

Together, DUAL, SOLID and I established a partnership agreement with a shared understanding that the research was ultimately for my PhD pursuits, though we would work together along the way, using a community-based participatory research framework, to advance evidence-based practice guidelines. We developed the research questions and selected four harm reduction committees that DUAL and SOLID were involved in. We developed interview questions to speak to various committee members. I observed committee meetings and collected relevant documents to understand their decision-making processes and how they included people who use drugs at their table. As I compiled preliminary results, I had meetings with DUAL and SOLID to review them and get their feedback. I also presented preliminary results to each of the committees for their input.

Throughout my studies, I continued to work with peer-run organizations of people who use drugs across Canada and assisted the Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs to develop and mobilize. In 2013, they held a national meeting of 14 peer run organizations and produced a report entitled Collective Voices Effecting Change: National Meeting of Peer-run Organizations of People who Use Drugs. As a result of my research, I experienced my own transformation whereby I have learned to shift from a position of leadership to one of facilitation. I assist groups in whatever way I can, following their lead and working with their strengths and aptitudes. Together, we developed another useful resource, Peerology: A guide by and for people who use drugs on how to get involved.

In addition to the summary cited above, my full dissertation, At the Table with People who Use Drugs: Transforming Power Inequities, is now available, should you be interested.

As part of CARBC’s lecture series, I will also be speaking on this topic at the Royal Jubilee Hospital, in the Patient Care Centre, Room S169 (Lecture Theatre), on Friday, June 3rd, 2016 at 10 am. If we want to be true allies to people who use drugs, let’s make our actions speak louder than our words.

_______________________________________________________

Lynne Belle-Isle, PhD, is a National Programs Manager with the Canadian AIDS Society and a Research Affiliate at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC, University of Victoria. She recently completed her PhD through the University of Victoria’s Social Dimensions of Health Program.