As researchers, our ultimate goal is to provide evidence-based information that will go on to inform policy and practice. Recently, we were lucky enough to have the opportunity to do just that.

For 18 months, the Centre for Addictions Research of BC (CARBC) has been collaborating on a project with the BC Ministry of Health. The Ministry’s initiative was to create 500 substance-use treatment spaces throughout the province; however, they wanted to know where these spaces would be best utilized. Would it be in the more Northern communities where substance-use treatment is scarcer? Or would it be in more busy urban areas where demand for these services is higher? These were some questions that a small team here at CARBC, alongside some key individuals within the Ministry, sought to answer.

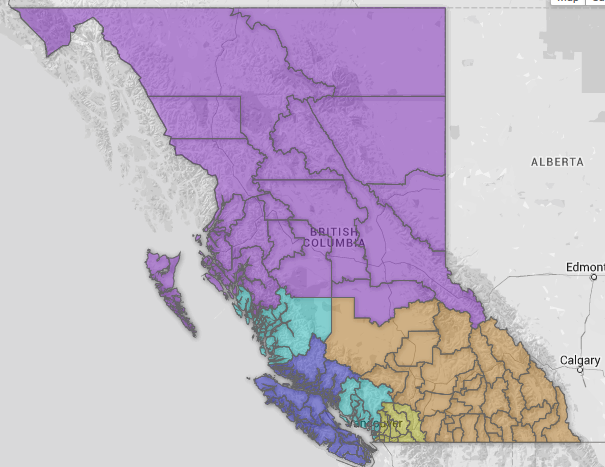

From a health service delivery perspective, British Columbia is divided geographically into health authorities (HAs), health service delivery areas (HSDAs), and local health areas (LHAs). This is a nested structure where the 89 LHAs nest within the 16 HSDAs, which in turn nest within the five larger HAs.

We set forth to replicate a needs-based planning model developed by Brian Rush and colleagues (2014). This model applies a number of different parameter estimates based on substance-use issues reported by population survey data. The estimates were derived from an extensive literature review as well as input from a national review of experts. For example, in tier 4 (i.e., specialized care functions targeted to people assessed/diagnosed as in need of more intensive or specialized care), Rush’s model estimates that 60% of the help-seeking population will require withdrawal management services.

Further subdividing withdrawal services into three specialized types the model estimates that 36.8% of those people will require home-based/mobile treatment, 52.6% will require community/residential treatment, and 10.5% will require complexity-enhanced/hospital-based treatment. We created population estimates from aggregated 2009/2010 results of the Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Survey (CADUMS), a national telephone-based survey that has been ongoing since 2008, for each of the five tiers or levels of substance issue needs, stratified by problem severity. The parameter estimates were applied and the number of individuals 15 and older in each Health Authority (i.e., Interior, Fraser, Northern, Vancouver Coastal, and Vancouver Island) requiring specialized services and supports (e.g., withdrawal management services, community services and supports or residential services and supports) was calculated.

The aforementioned collaborative project resulted in a report for the health authority representatives. The estimated number of in-need services was then compared to current capacity to create a gap analysis. This gap analysis is being used to explore opportunities to re-allocate resources to better match need-based planning.

This collaborative project between CARBC and the Ministry of Health provided evidence-based research to inform British Columbia’s future substance use treatment planning. This project also helped foster a long-term working relationship with Ministry of Health and Health Authority staff that will continue to build on the experiences and lessons learned from this successful collaboration.

Authors:

Chantele Joordens and Scott Macdonald, Centre for Addictions Research of BC

Joanne MacMillan, Ministry of Health

*Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC