Fentanyl-related overdoses have dominated the headlines in BC—and across the country—over the past year. Deaths involving the synthetic opiate narcotic, which is roughly 50 to 100 times more toxic than morphine, have increased five-fold in British Columbia over the past three years. But despite repeated warnings from provincial public-health bodies and alerts through community-based harm reduction supply distribution sites, fentanyl overdoses continue to rise—particularly among people who do not inject drugs. Clearly, despite efforts on the contrary, the message was not getting through to this population of users.

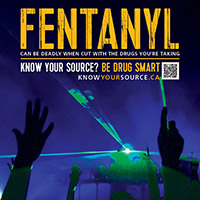

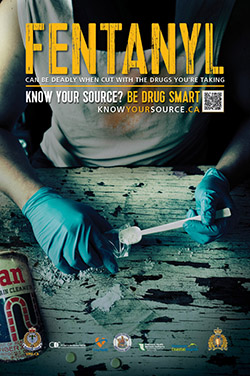

If you live in BC, you may have seen these posters pop up in your Facebook feed or at a local bar over the past few months. They’re the result of a campaign put together by BC’s Drug Overdose and Alert Partnership (DOAP), a multi-sectoral committee which works closely to monitor harms and deaths from substance use. After an emergency meeting in January 2015, the DOAP set to work crafting a campaign that would get the word out to a population of substance users that traditional methods weren’t reaching.

Coroner’s data revealed that most of the people who were dying of fentanyl-related overdoses (deaths where fentanyl was detected, either alone or in combination with other drugs) were between 19 and 40 and were not injecting drugs, which meant they were likely not accessing harm-reduction-supply distribution sites and likely had missed the posters and alerts that had been put out through those avenues. DOAP members decided to develop a targeted public safety campaign aimed at people aged 19-40 using public posters, Facebook advertising and a website. Thus, the “Know Your Source? Be Drug Smart” campaign was born.

It’s one thing to decide how you are going to get the message out; deciding what the message will be is a totally different beast. We looked to campaigns like Toronto Crime Stoppers’ Cookin’ with Molly, as well as social marketing and behavior changed theories. The aim of this campaign was at the first stage of behavior change theory: to simply raise awareness about what fentanyl was, where it could show up, and how to deal with and prevent an overdose. Evidence from published literature also suggested that the best PSA campaign required input from the target audience, so we held two focus groups with youth.

As for the visual content, it was felt that the images needed to have a bit of shock value to grab the viewer’s attention, but have sufficient detail to convey the message. The idea was not to tell people to not use drugs (because we know that doesn’t work), but for people to learn about what might be in their drugs so that they could be aware of what to look out for. In some sense, the entire campaign took on a harm-reduction approach – we knew people were using and wanted to provide them adequate info to reduce harms from fentanyl use.

After the working group developed draft messages and posters, they were reviewed by staff working in the areas of public health, mental health and substance use, young professionals who personally use drugs or have friends who use drugs in social settings, and at-risk youth who use substances in social settings, including at music festivals or concerts. Feedback helped us to tweak the campaign images and campaign taglines into ones that drug users were more likely to respond to. Public health staff worked with the BC Coroners Service and the BC Drug & Poison Information Centre to compile accurate information about fentanyl for the public and for health care professionals. All the information was integrated into a central website, Know Your Source, a one-stop shop for tips on prevention, harm reduction and treatment.

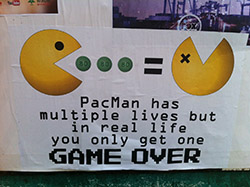

As fentanyl-associated deaths continue, the Know Your Source campaign provides accurate information and resources across the country. The messages have also inspired some people to create their own posters; these Pacman themed posters have been spotted around Vancouver. The Know Your Source awareness posters and messages have been adapted for use in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and discussions are underway for their use in Manitoba and Ontario.

Author: Ashraf Amlani, Harm Reduction Epidemiologist, BC Centre for Disease Control