At the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition (CDPC) one of things we’ve noticed is that any blog we publish on cannabis regulation attracts more attention than any other topic. This is because there’s widespread interest in discussion of changes to the laws that govern cannabis. Unfortunately when it comes to the nuts and bolts of cannabis regulation – in other words – the how of regulation, interest tends to drop off. This is because regulation is actually rather tedious. This is borne out by the length of the proposed regulations for legal recreational cannabis markets in the U.S. states of Washington (43 pages) and Colorado (72 pages). That’s why I’m making a special plea to you our dear readers to stay with me as I say a few words about what regulation might actually entail.

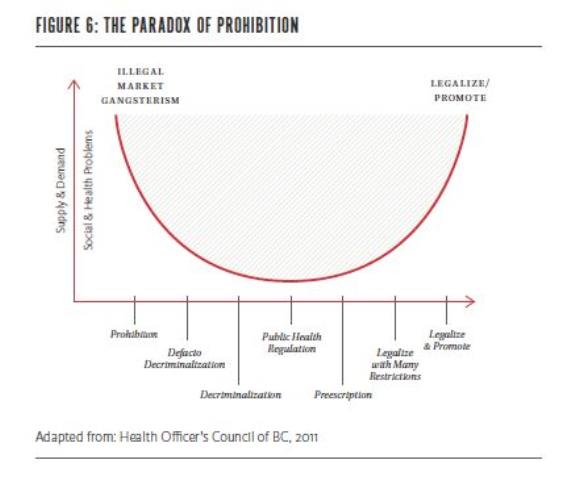

I think it’s fair to suggest that both the CDPC and the Centre for Addictions Research of BC favour a model of regulation that draws on the best evidence from public health regulation of alcohol and tobacco. But when it comes to cannabis regulation the devil really is in the details. There’s no magic bullet that will make all the current problems with cannabis prohibition disappear. But thanks to the Health Officer’s Council of BC, some of the heavy lifting when it comes to creating models for drug regulation has been done. If you’re curious, check out their 2011 report. As you can see from the diagram drawn from that report, regulations for cannabis should not be so loose that they create a free and unregulated market for cannabis; nor should regulations be so overly restrictive that we end up reproducing the negative aspects of the current underground economy (control by organized crime, etc.).

At the same time we need to be clear about the goals we hope to achieve with a legal regulated market for cannabis. Ideally our regulations will help protect and improve public health, reduce drug related crime, protect the young and vulnerable, protect human rights and provide good value for money. So what are some of the things we’ll need to consider? How about we start with the basics.

Presumably legalization would entail the removal of cannabis from Schedule 2 of the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, followed by its inclusion in the Food and Drug Act. It seems like the next logical thing to do would be to turn over the regulation of cannabis to the provinces, in the same way that alcohol is currently regulated. We would want to ensure that there is at least some consistency across the provinces so that means somebody at the federal level will have to oversee the regulations as they emerge. That’s the easy part because legalization would ALSO entail consideration of at least the following issues: production, product, packaging, vendor and outlet controls, marketing controls, creation of a system of regulators and inspectors as well as on-going research and monitoring.

For this blog post, I want to focus on production and product controls. Future blog posts may consider the other items on the long list noted above. My comments meant to stimulate discussion of regulation rather than to propose firm rules for how a legal recreational cannabis market might operate.

In Canada, marijuana is currently produced in one of two ways – under existing legal medical marijuana guidelines or in illegal circumstances. Growing marijuana takes places in a vast array of situations ranging from a few plants grown for personal use all the way to large-scale industrial size operations with 100’s of plants.

Thus regulating the growth of marijuana for a legal recreational market will not be simple. Many people are very attached to their small-scale gardens, and it would be difficult to impossible (as well as undesirable) to eliminate growing marijuana for personal use. And it’s important not to turn the whole thing over to heavily capitalized large scale commercial producers who main motivation is profit, especially since the range of available strains of marijuana has been the result of innovation by many small-scale growers. Thus, we need to ensure that the best practices in indoor, outdoor, personal, commercial production are preserved while ensuring that cannabis is produced in safe and clean facilities. We will also need to decide who is the appropriate authority for regulating growing operations: municipalities or provinces or some combination of both. Neither seems overly keen on this role so they will require some convincing.

Okay if your head doesn’t hurt yet lets turn our attention to product controls. Product controls include issues like price, age limits, potency, permissible preparations (edibles, tinctures, etc.), quality control, and labeling and packaging requirements. Price is a key issue when it comes to meeting public health goals. Price can help shape sales and thus use of cannabis, so we want to ensure that pricing reflects what we’ve learned from alcohol – namely that alcohol consumption is sensitive to price and that price must in some way be related to potency. Related to price is taxation – at what point in the chain from seed to sale will cannabis be taxed and at what rate? And what preparations will cannabis regulations allow? Plant materials, tinctures and oils, edibles? Right now Canada’s medical marijuana access program only allows for the distribution of plant material. Clearly this is a very limited approach given that the medical cannabis dispensaries have created a range of edible and other products that eliminate the necessity of smoking cannabis. We will also need to decide where we stand on potency: in other words will we put limits on how potent products can be, and given that there are over 100 cannabinoids, how will we decide which ones we want to measure and regulate?

Okay so I haven’t covered other essential issues like vendor controls, marketing and evaluation and monitoring but I think you get the picture. Regulation is by no means a simple matter, but it can be done. In fact, experience from legal recreational markets in Washington and Colorado will provide valuable insights that can inform Canada’s approach. And regulation has the potential to create conditions where cannabis production and use is a whole lot safer than the current prohibition approach.

*Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC

Connie Carter, Senior Policy Analyst, Canadian Drug Policy Coalition