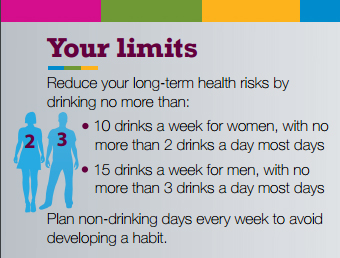

Health advocates, when referring publicly to alcohol use, are inclined to emphasize ways in which it elevates risk for harms. No surprise there. Drinking more on any occasion leads to greater intoxication and increased risk of receiving and causing injury. More frequent regular use increases likelihood of eventually contracting sustained illnesses. Drinking that has become a daily routine, or involves difficulty at times in stopping, raises prospects for developing a detrimental dependence on alcohol. Formal research indicates broadly-applicable consumption thresholds for added risk, so health proponents readily advise moderate patterns of use. Canada’s low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines are one such set of recommendations in regard to maximum use on a weekly basis, on normal days, on special occasions and in certain situations.

The Alcohol Reality Check is a self-screening tool that draws on scientific study and those Canadian guidelines in particular. It provides people with an anonymous online opportunity to see, through personalized feedback, how their regular drinking pattern compares or contrasts with various levels of risk to long-term health, for immediate harms and for developing unhealthy habitual use. We believe it’s a little exercise worth doing periodically.

Encouraging people in healthier use is more than a public social marketing approach broadly exhorting adherence to behavioural guidelines. That approach carries some liabilities. One is the authoritarian air social marketing readily assumes in prescriptively telling people what they should do. By contrast, a consistent health promotion approach seeks to help those who use alcohol to better manage their own wellbeing by becoming more intentional in their drinking. A tool like the Alcohol Reality Check accomplishes more, health promotion-wise, not just by acquainting people with the guidelines, but by going beyond that to prompt reflection, affirm agency and self-efficacy, and encourage adoption of a course of action that will align with the person’s own reconsidered aspirations of wellness.

A further shortcoming to typical social marketing has to do with its isolating orientation in representing health as an individual issue and not also a collective, mutual matter: people tend to be addressed as singular entities separate from and uninfluenced by their relational connections. The framing of health as absence of personal injury or illness is also inadequate. It ignores further, positive dimensions long-recognized by the WHO’s definition of health as encompassing holistic wellness in physical, mental, social and economic respects. People, whether as individuals or in groups, drink (and some deliberately get drunk) to receive certain benefits that enhance their sense of wellbeing. Experience of pleasure, fun, is part of this.

Failure to acknowledge and address this in a way that is appreciative, even when constructively critical (e.g., asking whether there might be more advantageous ways of securing social benefits), is often an obstacle to meaningful, productive conversation that invites contemplation of change. In respectfully attending to cultural considerations for use, qualitative research confirms a real disconnect on the part of young adult drinkers with guidelines that come across as indifferent if not oblivious to common motivations for and gains derived from drinking. Compounding this deficiency is the way in which social media serves to reinforce much of this motivation (with the alcohol industry ably exploiting both this incentive and the popular mechanisms of affirming it, while narrow health messaging is often a stranger to both).

Alcohol Reality Check is not a social networking site, but Hello Sunday Morning is. Health promotion efforts like it support personal interaction and collective dialogue around how people can relate to alcohol in ways that capture benefits and not just avoid harms. While potentially necessary and quite beneficial as a vehicle of communication and an aid to discussion, a social networking platform is not sufficient for building community health. What is vital is to utilize a variety of means to engage people in conversation that helps them to collaborate in joint initiatives to manage their shared health in relation to alcohol (as in regard to other areas of opportunity and challenge in their civic life).

Tim Dyck, Research Associate, Centre for Addictions Research of BC