We hear a lot about patient-centred care in substance use services, but what about family-centred care? Family members are important sources of support for those accessing substance use services. However, family inclusion is not always regular or customary practice within substance use systems and services. In the midst of an unprecedented public health overdose emergency, families are vital first responders who can provide life-saving first aid and are key resources and facilitators in accessing and using substance use services.

With this in mind, Island Health and CARBC partnered to explore family involvement in out-patient substance use treatment services across youth, adult and senior’s programs. The purpose of this research project was to understand, from the perspective of Island Health service providers, the current landscape of family inclusion and what might be possibilities for increasing practitioner and organizational capacity to facilitate responsive family inclusion in substance use treatment services.

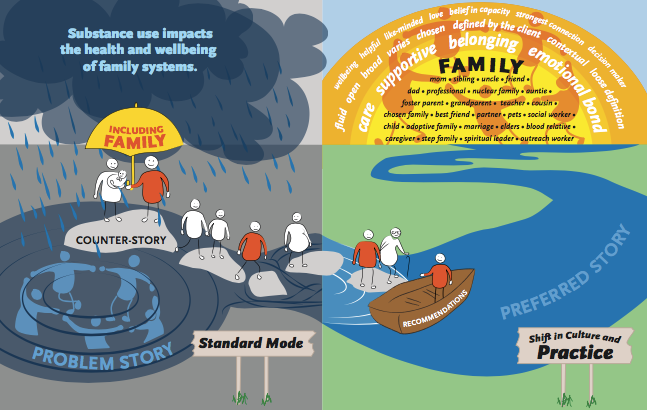

What do we mean by family and why is family inclusion important? We found that providers had a broad definition of family. Family was considered to be anyone in a person’s circle of care who contributed love, connection and closeness. Examples of family members were many and included biological relations and chosen relations such as friends, partners, neighbours, and in some cases pets. Family inclusion was described as being a necessary means of reducing consequences of substance use throughout generations, while fostering wellness for the individual accessing services and the broader family system. Families were recognized as being integral sources of support and safety for people involved with substances and vital resources beyond immediate, time-limited formal interventions.

What gets in the way of family inclusion? While we heard service providers emphasizing the importance of family inclusion, in reality working within the health care system meant operating in ‘standard mode.’ Standard mode included dominant structural values privileging individualized and predominantly biomedical service philosophies that often left families out of the picture. In spite of this, service providers described ways of disrupting standard mode and working towards family inclusion. They talked about trying to make time to support families and increasing availability by way of telephone and/or in-person connection. Providers emphasized the importance of offering compassion and presence while maintaining openness to the potentials of expanding the scope of services to involved family members.

How might family inclusion become a regular and customary practice? In order to understand how to change standard mode, we asked research participants to describe their “preferred story.” They expressed the importance of sparking a broad societal, organization and programmatic culture shift towards family inclusion. Such a shift would include emphasizing the effects of substance use on families and the importance of mitigating ongoing intergenerational ripples of substance use impacts in families affected by substance use. An overarching culture shift would require openness and access to relational, strengths-based and capacity-focused ways of knowing and understanding substance use and working with families affected by substance use.

Read the full report to learn more about recommendations and future directions for increasing family involvement in substance use service.

For further information on this project contact Stephanie McCune at stephanie.mccune@viha.ca or Bernadette Pauly at bpauly@carbc.ca

Stephanie McCune, Manager, Practice Support Program, Island Health

Bernie Pauly, Scientist, Centre for Addictions Research of BC

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC.