It has been well known since historic times that cannabis may cause a variety of psychiatric symptoms. In fact, the desire to take cannabis or marijuana is primarily to obtain mental effects, and the line may be thin even in an occasional user between experiencing a pleasant and exciting psychoactive effect and a real psychotic episode. “Cannabis psychosis” is a term widely used for psychotic episodes resulting from cannabis use. These occur during or shortly after intake and may last days or weeks, but subside after discontinuation of the drug. They may require hospitalization and medication. Comprehensive summaries of mental health effects of cannabis have been published by Murray and Hall & Degenhardt.

It has often been debated whether use of cannabis can cause long-term psychotic states, and in particular schizophrenia and other chronic psychoses. Seeing patients with a combination of heavy cannabis use and schizophrenia, I was intrigued to assess the causal direction of the association. It was in the 1980s when I found out there was a survey on drug use in a national cohort of 50,000 Swedish 18-19 year old male conscripts (one year of military service was compulsory in Sweden until 2010) that we could link to data on occurrence of schizophrenia later in life. We found that those who reported use of cannabis in adolescence had a doubled risk of schizophrenia compared to those who did not use cannabis. With data on social background, psychological characteristics, and psychiatric condition assessed at conscription, we could control for such factors that might influence the association.

We have continued to follow this cohort and the men are now over 50 years old. The contribution of cannabis to new cases of schizophrenia has declined in occasional users but those who reported heavy use of cannabis in adolescence still have a twofold increased risk of schizophrenia, even at older ages. We do not know whether this is due to continued use of cannabis, or whether heavy early use could indeed have had very long lasting effects.

In recent years, several other studies have also found an association between cannabis use and later onset of chronic psychosis. A review was published in 2007 concluding that there is now “sufficient evidence to warn young people that using cannabis could increase the risk of developing a psychotic illness later in life.” The paper was accompanied by an editorial in which the prestigious journal the Lancet admitted that they had previously underestimated the risk of harmful effects of cannabis.

We recently studied the pattern of care of the patients with schizophrenia in our cohort of male conscripts, and it turns out that those patients with a history of cannabis use had double the number of total days in hospital and around double the number of hospitalizations that were twice as long in duration of those who did not have a history of cannabis use.

Thus, there is now evidence that cannabis is indeed a contributory cause of chronic psychoses, including schizophrenia. Certainly, cannabis is not the only cause of chronic psychosis. There generally needs to be other factors, such as genetic factors, personality characteristics, etc. to cause schizophrenia or other long-standing psychoses. It has been shown that the risk of psychosis in cannabis users is especially strong in psychologically vulnerable persons. Thus young people, and especially persons with mental health illness, should be warned about the risk of chronic psychotic disorders as an effect of cannabis use. Not only because of the risk of chronic psychosis, but also a number of other negative physical and mental side effects.

*Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC

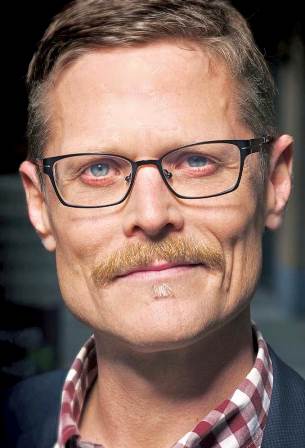

Peter Allebeck, Professor of Social Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden