Health Canada reports that the ability to drive or perform activities that require alertness may be impaired for up to 24 hours following a single joint. A report from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in the U.S. with expert advice from six toxicologists states that some investigators have demonstrated residual effects in specific behaviors up to 24 hours, such as complex divided attention tasks. The World Health Organization reports “human performance on complex machinery can be impaired for as long as 24 hours” after smoking a moderate dose of cannabis.

The source of the claim of 24-hour deficits from each of these above mentioned reports—just a few of many that exist in literature around cannabis impairment—is based on a single 1991 study by Leirer et al. The findings of this study has received an extraordinary degree of acceptance, but this study has multiple methodological issues, including a failure to randomize conditions, a failure to conduct a pre-test of the methods, and retention of unreliable measures. Let’s take a closer look at some of the problems with this study.

The study’s claim that performance deficits continue 24 hours after using cannabis is not justifiable based on the methods reported. The researchers did not report random assignment of conditions or a crossover design, which is when everyone participating in the study receives all the treatments being investigated (in this case, it would mean all the subjects smoking both the cannabis cigarette and the placebo at different points). These two approaches are essential to reduce the likelihood of bias in a study. In describing their procedures, Leirer always refers to the marijuana condition first. In this type of research design, the marijuana condition is confounded with practice effects (i.e., subjects do better on tasks with more experience). Furthermore, the authors did not report any blinding of researchers, which is the practice of ensuring that researchers and/or participants are unaware of information that might influence their behaviour or decision. This is an important component of high quality studies, and its omission opens up the possibility of researcher bias.

Finally, two measures (far target detection and engine malfunctions) were dropped from the analysis after data collection was complete because they were not reliably recorded. The proper procedure for a study is to decide on valid measures at the onset of the study and to keep them throughout the study, not to drop them after looking at the data. Interestingly, the data for near targets was kept, even though the same procedures were used to collect this data as far targets. At 24 hours, subjects performed worse than any other time point, including 15 minutes after use!

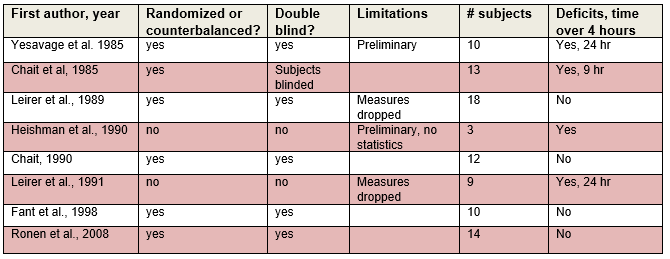

Are there other, better studies? Absolutely. I found eight laboratory studies that examined long-term performance deficits from cannabis use. Three of them (Chait et al., Fant et al. and Ronen et al.) were much higher quality with randomized/counterbalanced and double blind designs and no other major limitations were found. None of these studies found performance deficits that exceeded 4 hours.

The claim of 24-hour deficits from a cannabis joint in occasional users is dubious at best. So how did prevailing scientific thought become so distorted?

I have a couple of explanations for why this has happened. First is publication bias. In science, there is a bias among journals to publish findings that are statistically significant and consistent with researcher’s hypotheses. This accepted bias toward publishing studies with significant findings also can be reflected in conclusions that authors of review articles choose to report – that is, there is a tendency to ignore non-significant findings in favour of ones that are significant.

Second, there is a bias toward reporting findings that are consistent with a public-health perspective. The vast majority of research in the illicit drug field is aimed toward describing the harms associated with use and how to prevent, treat or reduce them. If harms of illicit drugs are not found, then the reason to be for focusing on public-health issues cannot be achieved.

Conclusion

In this series, I have compared our knowledge of alcohol with cannabis in relation to driving and Canadian legislation to reduce driving casualties. The safety benefits of the breathalyzer for detecting alcohol impairment are substantial and undeniable. A large body of credible research shows alcohol negatively affects performance in a dose-response relationship and the BAC level from breath tests is an excellent measure of performance deficits. As well, alcohol is eliminated from the body at a constant rate and is water soluble, which means there is a close relationship between alcohol in the blood and performance. Although alcohol can cause long-term effects, such as those due to hangovers, the breathalyzer cannot detect such deficits. For cannabis detection, the story is much different. The blood tests are inconvenient, difficult to administer in a timely fashion and poor relationships between low levels of THC and performance deficits. Impairment at the proposed 2 and 5 ng/ml cut-offs appear to be very low compared to the impairment at 0.05% and 0.08% BAC for alcohol. Using such low cut-offs to compensate for time delay in getting the blood samples is not defensible in light of the variable rate at which THC blood concentrations decline over time and between individuals. Finally, the theory of 24-hour impairment does not provide a rationale for adopting low THC cut-off levels.

Although research does show cannabis impairs performance, we don’t have any valid method of determining these deficits, unless blood tests are administered almost immediately when impairment is suspected, and a much higher level is found. The proposed legislation for cannabis impaired driving does not pass the standard we should expect for Canadian criminal law.

Read our Cannabis and Driving blog series:

Part 1: Proposed federal legislation on cannabis and alcohol impaired driving

Part 2: The safety benefits of alcohol breath-testing: a research summary

Part 3: The safety benefits of THC blood testing: a research summary

Scott Macdonald is the Assistant Director of research at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and a professor in the School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria. He has been an expert witness in several cases related to drug testing in the workplace. Material from this series is taken from his book, Cannabis Crashes: Myths and Truths, Lulu Press.

Scott Macdonald is the Assistant Director of research at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and a professor in the School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria. He has been an expert witness in several cases related to drug testing in the workplace. Material from this series is taken from his book, Cannabis Crashes: Myths and Truths, Lulu Press.

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.