If you’ve ever driven when really tired, or been in a car with a driver who’s really tired, you know what “impaired driving” feels or looks like. (For those who don’t: in a nutshell, it’s kind of scary.) Chances are, though, you don’t think of being tired as something bad. Instead, you know that being tired means you should be in bed, recuperating by sleeping for a while.

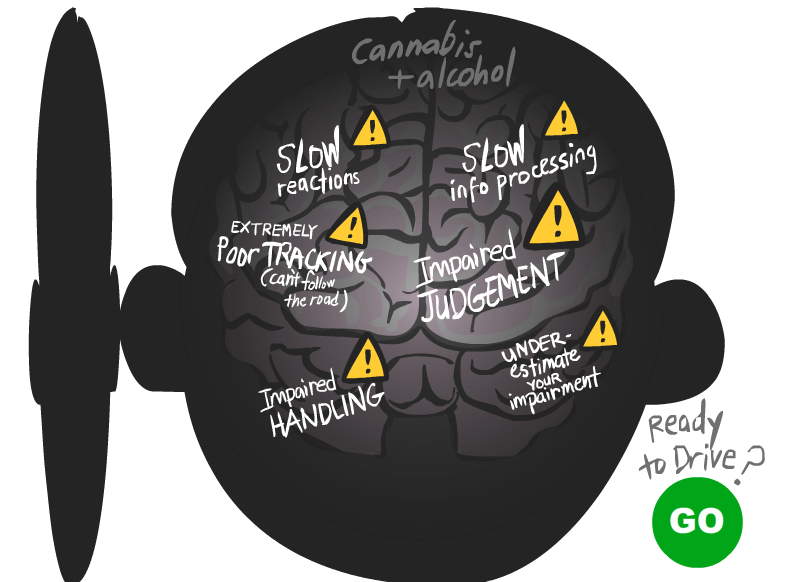

Drug-impaired driving is much the same thing. It’s less about whether a drug is good or bad, and more about where you are when you’re feeling a drug’s full effects. While avoiding intoxication may be the best option with any psychoactive drug, if it happens, the safest place to be enjoying or reversing the buzz is at home, at a pal’s house or in the back of a taxi or sober person’s vehicle. Almost anywhere but behind the wheel.

Even though we all know we shouldn’t drive impaired, it still happens.

- In 2012, 6.5% of BC drivers tested positive for alcohol, and 7.4% tested positive for other drugs, cannabis and cocaine being the most commonly detected substances, according to a roadside survey report.

- ICBC reports drug impairment (involving alcohol, illegal drugs and medications) was the key factor in 23% of fatal car crashes in 2013 (speed was key in 28%, and distraction in 29%).

- Over the last five years, an average of 86 people per year lost their lives in impaired driving crashes on BC roads.

So, what’s going on with us? What narratives are running through our heads about our rights and responsibilities as drivers? What are the best ways to change some of our beliefs and behaviours? These are the kinds of questions we not only need to be asking ourselves, but should also form the foundation of our drug education programs in schools.

Instead, most of the conversations we have with young people about drugs are not really conversations at all, but lectures aimed at scaring students into saying whatever the adults in the room want to hear. The problem with this approach is that it isn’t working. Young people, particularly young males, continue to make up the bulk of those taking unnecessary risks with substances and vehicles. We should be wondering why, and we should be talking to students more often about the things that drive their decisions to drive under the influence.

Honest, open and real conversation about alcohol and other drugs is one of the goals of Drugs and Driving, a project involving a range of classroom learning activities, a variety of web apps, and even a free iPhone app. Drugs and Driving is designed for Grade 10 students but can be used in other grades as well. The program is less about telling kids about the dangers of drugs and driving and more about helping them reflect on a range of issues related to impairment. What are the things that might cause impairment? How do I know if I am impaired? Why should I care? How do we make decisions? How can I influence the decisions of my peers? These are important questions for all of us.

Author: Nicole Bodner, Centre for Addictions Research of BC

**Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC.