Cannabis is neither completely harmless, nor is it a cure-all, but with polls showing that Canadians overwhelmingly support cannabis policy reform, it’s fair to assume that most people no longer believe that legalization would lead to the end of the world. Yet, some who support reform nonetheless have concerns that adding yet another legal drug (alongside alcohol, tobacco and pharmaceuticals) for society to struggle with might result in an increase in use.

But what if the legalization of adult access to cannabis also resulted in a reduction in the use of alcohol and other drugs? What if rather than being a gateway drug, cannabis actually proved to be an exit drug from problematic substance use? A growing body of research on a theory called cannabis substitution effect suggests just that.

In a nutshell, substitution effect is an economic theory that suggests that variations in the availability of one product may affect the use of another. Perhaps the best example of deliberate drug substitution is the common prescription use of methadone as a substitute for heroin, or e-cigarettes or nicotine patches rather than tobacco smoking.

However, substitution effect can be also be the unintended result of public policy shifts or other social changes, such as changes in the cost, legal status or availability of a substance. For example, in 13 U.S. states that decriminalized the personal recreational use of cannabis in the 1970s, research found that users shifted from using harder drugs to marijuana after its legal risks were decreased (Model, 1993).

Findings from Australia’s 2001 National Drug Strategy Household Survey specifically identify cannabis substitution effect, indicating 56.6% of people who used heroin substituted cannabis when their substance of choice was unavailable. The survey also found that 31.8% of people who use pharmaceutical analgesics for nonmedical purposes reported using cannabis when painkillers weren’t available (Aharonovich et al., 2002).

Additionally, a 2011 survey of 404 medical cannabis patients in Canada that colleagues and I conducted found that over 75% of respondents reported they substitute cannabis for another substance, with over 67% using cannabis as a substitute for prescription drugs, 41% as a substitute for alcohol, and 36% as a substitute for illicit substances (Lucas et al., 2012).

This and other evidence that cannabis can be a substitute for pharmaceutical opiates, alcohol and other drugs – and thereby reduce alcohol-related automobile accidents, violence and property crime, as well as disease transmission associated with injection drug use – could inform an evidence-based, public health-centered drug policy. Given the potential to decrease personal suffering and the social costs associated with addiction, further research on cannabis substitution effect appears to be justified on both economic and ethical grounds.

Maximizing the public health benefits of cannabis substitution effect could require the legalization of adult cannabis use, as currently being implemented in Colorado and Washington State. So the question is: do we have the courage to abandon long-standing drug policies based on fear, prejudice and misinformation, and instead develop strategies informed by science, reason and compassion?

*Please note that the material presented here does not necessarily imply endorsement or agreement by individuals at the Centre for Addictions Research of BC

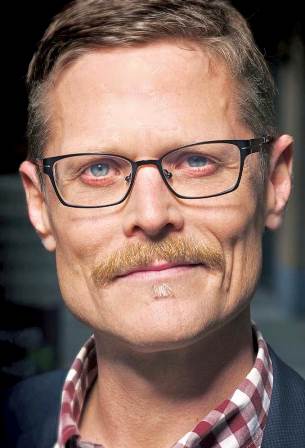

Philippe Lucas is a Graduate Researcher with the Centre for Addictions Research of BC, President of the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies Canada, and a founding Board member of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. In 2012 he was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal for his work on medical cannabis.