Why Siberia?

As the First World War was being waged, the Russian October Revolution in 1917 derailed the Russian campaign and deeply disturbed the Entente powers at the same time. Bolshevik control over Russia meant that what had previously been a reliable ally suddenly became unstable and volatile. The Russian focus on fighting their own war between the Imperial White Army and the Bolshevik Red Army meant that they would no longer be able to fully assist in the fight against German forces in the rest of Europe.

There was an immediate desire to intervene in Russia by the Entente powers, as they wished to help the White Army regain power, among other motivations. At the ports of Murmansk, Arkhangelsk, and Vladivostok, huge amounts of goods destined for the Entente forces had been accumulating, intending to be sent on when necessary. Now that Russia was under the control of a hostile and violent force, these resources were threatened—not only by the Bolsheviks but also by possible German encroachment into Russian territory, should the unstable situation render the country unable to withstand German attacks.[1]

There was also a wish to help extract the now trapped Czechoslovak Legion, who were attempting to make their way to Vladivostok along the Trans-Siberian Railway, which was now controlled by the Bolshevik forces. This group of soldiers had been fighting alongside Russian forces on the Western front. Despite the seeming agreement by the Bolsheviks within the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk to allow the Czechoslovak Legion to leave, they still had a long, difficult journey ahead of them, with much fighting involved before they were able to make their way home, because they were not able to go straight home across Europe.[2]

By the summer of 1918, the decision had been made to intervene in an attempt to stop the growth of Bolshevik power. The creation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) was approved and they set out to join forces from Japan, the United States, Italy, France, Serbia, Romania, China, and Poland. The city of Vladivostok’s location on the eastern coast of Russia meant that it was easily accessible from the Western coast of Canada, and so the decision was made to muster the forces in Victoria and set out from there.[3]

Preparations for Departure

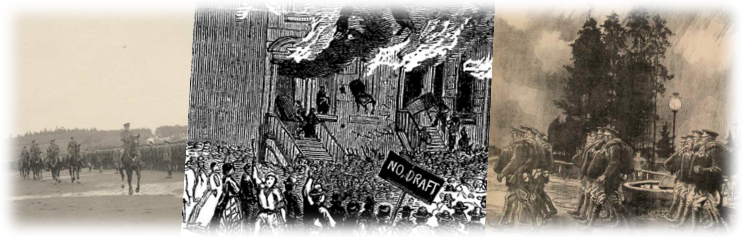

The training grounds at Willows Camp had trained many soldiers for World War I, and so were considered the perfect place to train the returning soldiers for their new mission in Siberia. Troops began to gather in early December, coming on trains from Eastern Canada, which may in fact have carried the Spanish Flu to the west coast. Though many of the troops were in fact volunteers—soldiers unwilling to return to civilian life quite so soon—a major portion were conscripts, something that would turn out to be more of an issue than officers had ever imagined. Major-General James H. Elmsley was in control of the operation, and preparations began to deploy troops to Vladivostok.[4]

The force put together to fight in Siberia consisted of 11 groups including two infantry battalions—the 259th and 260th—as well as the “B” Squadron of the Royal North-West Mounted Police, Cavalry Division, and a machine gun company.[5]

The conditions at Willows Camp as well as at two other camps in New Westminster and Coquitlam were not luxurious—it had been a wet fall and winter, and so the camps were muddy and damp—not ideal conditions for soldiers who had only recently returned from the horrors of the trenches in Europe.[6] Nevertheless, the soldiers were drilled and prepared for a return to active duty.

[1] Roy MacLaren, Canadians in Russia, 1918-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited, 1976), 127.

[2] Canadians, 3.

[3] Benjamin Isitt, From Victoria to Vladivostock: Canada’s Siberian Expedition, 1917-19 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), 64.

[4] Victoria, 72.

[5] Victoria, 72-3.

[6] Canadians, 175.