Church Pacifism

During the Great War a significant amount of support came from churches. However peace churches, which were pacifistic and objected to violence, had no wish to participate in the conflict in Europe and did not mobilize support for the war as other churches were apt to do. One such church is the Society of Friends (the Quakers), an extension of which had been established in Victoria in 1913, just before the onset of the Great War.

It is prudent to point out that while the Friends objected to the war, and in particular conscription, there was still a willingness to support those soldiers who did go off to the front. In June of 1916 at one of their meetings it was advised that the members of the congregation make the effort to correspond with those that they knew at the front or who had just recently enlisted. Such correspondence could not have been for any other sake than to offer support to those who were going off to war, despite the personal objections that the individual may have personally had regarding the War. However, for the most part, any discourse regarding the war was limited. Discussion of the Great War is conspicuous in its absence given the fervor expressed in other churches in support of the war effort. Pacifism, in its sincerest form, is expressed through the absence of war, not only in action, but discussion as well, a difficult thing to accomplish given the extent of the conflict and the ardent support for the war effort.

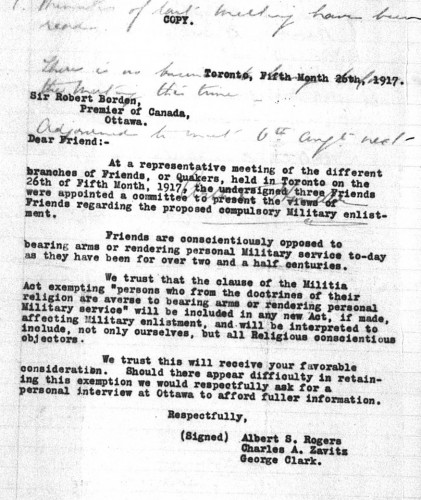

The Friends, and other peace churches, do provide an interesting view of where the war was not the dominant topic and influence. As a result of this there is no indication that the Friends took any action against the war effort until concern was expressed leading up to the implementation of conscription in 1917. Conscription was part of the Military Service Act, which required men of a certain age to serve if they were drafted. There was concern that those who held pacifist beliefs due to their religion would not be exempted from the draft. Concerned by this a letter was written to Prime Minister Borden on behalf of the Quaker congregations in Canada stating their unease over the Act and imploring the Government to include a clause, which would address the concern of peace churches. Members of peace churches were successful in having their voices heard and were excused from service on the front; however, this did not prevent members from being drafted as servicemen in non-combative situations. The Act contained a “conscience clause” but this was made only in reference to those who would be exempted from combative service.[1] Troubling for those affected, as they would still be helping move the “military machine.”[2] In Canada there were only two instances of individuals losing their tribunals and subsequently refusing non-combative service that resulted in them being sentenced to a term of hard labour.[3] No such cases occurred anywhere else in Canada including Victoria.

In terms of the draft few Friends would have been affected by it as many members were above the required age, this being the case in Victoria, and most meetings took place in rural areas, leaving those few who were eligible exempted due to the fact that they were farmers as well. Despite this, conscription was still subject to discussion at meetings, things like the letter to the Prime Minister were read at meetings and national newsletter were distributed so that Friends across the country could stay informed if they needed to apply for a certificate of exemption. Fortunately, the pacifist beliefs of peace churches were largely respected in Canada following the Military Service Act and a conflict of ideology did not manifest.

The Society of Friends and other peace churches are an example of a different form of war resistance, while significantly less dramatic than other conflicts in Canada surrounding the implementation of conscription, they are no less significant in their views towards to the war and how they chose to act upon and express them.