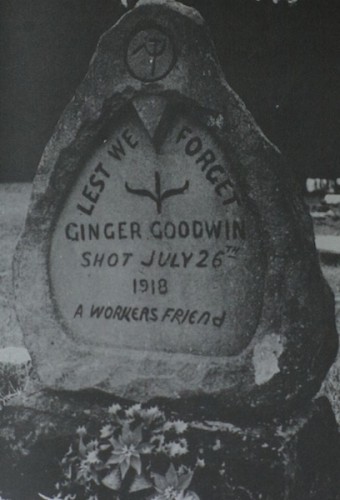

Death: Accident or Murder?

Ginger Goodwin’s death on July 27, 1918 was the result of an unfortunate, but inevitable encounter with the provincial law. Goodwin had been hiding in the mountainous countryside of the Comox Valley near Comox Lake, holed up with several other draft evaders. Goodwin had been relatively safe for most of the summer – the police constable for the community of Cumberland was Bob Rushford, a veteran of the war and a friend of Goodwin from his earlier sojourn in Cumberland. Rushford and the community of Cumberland was sympathetic to Goodwin’s desertion, through provide advice on staying low and providing the deserters with caches of food and mail.[1]

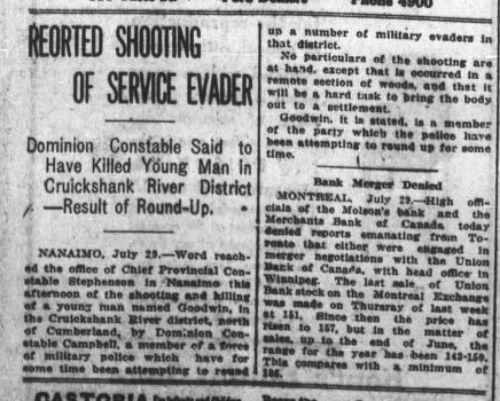

However, due to federal pressure to reign in the deserters for enlistment to meet the quota of soldiers to send overseas, the provincial government began swearing in special police constables and, with the aid of the Dominion Police, began man-hunts with posses across the province. Dan Campbell, a former Victoria Police constable having been dismissed in 1905 for bribery, was one of these posse members searching the Comox countryside. Campbell had spent his time between 1905 and 1918 joining various milita as a special constable across British Columbia and running a hotel in Colwood.[2] Campbell’s proficiency at bush whacking and marksmanship made him an invaluable member of the party.

The orders were to find Goodwin and the others, apprehend and send them on their way as conscripts. Yet in the afternoon of July 27, while alone, Campbell encountered Goodwin on a trail, as Goodwin was picking blackberries, and shot him.[3] Campbell claimed that Goodwin had raised a rifle at him and Campbell shot in self defense.[4] On the thirty first of July, four days after as the Dominion Police began their inquest, Campbell was arrested by the Provincial Police and charged with manslaughter for the shooting.[5] There was a significant amount of suspicion that arose from his death. For instance, there was controversy over whether or not Goodwin was even armed and if he was, had he actually raised his rifle in an attempt to aim at Campbell?[6] The inquest autopsy disregarded two doctors from Cumberland who were familiar with Goodwin, replaced instead with a Courtenay doctor.[7]

However, the subsequent grand jury that was formed first in Nanaimo and later Victoria, found no conclusive evidence that Campbell should be tried for manslaughter.[8] The argument that prevailed by Justice Denis Murphy of the BC Supreme Court was Campbell was justified in acting out of self defense during a time of war – making the murder into an act of nationalistic passion, and therefore not a crime.[9] This provided the explanation of Campbell’s conversations with the other members of the posse, how Campbell insisted that he would be attaining the deserters whether they were dead or alive.[10] With this statement the jury declared ‘no bill’ be made in regards to trying Campbell, who then went free in October of 1918.[11]

There were many people at the time who were incensed by the death of Ginger Goodwin. Bob Rushford had asserted through the remainder of his life that Goodwin was unarmed when he was shot.[12] Campbell received a very cold welcome in Cumberland directly following the incident. The community was grieving over the loss of Goodwin and angry towards Campbell. Cumberland’s anger was represented in the refusal of any food service for Campbell but that easily could have escalated given how resentful the town was of him and the Dominion Police in general.[13] Campbell was spared from any vigilante justice, with Rushford arresting him and taking him south to Victoria on the thirty first of July. After Campbell’s acquittal, he maintained for the remainder of his life that he had acted in self defense of his life alone, regardless of any testimony that suggested he may have had intention to murder Goodwin, or any of the deserters.