The Mutiny

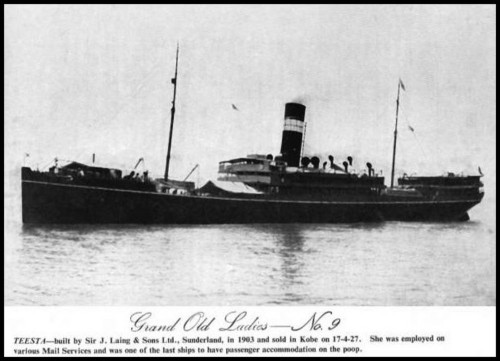

On the morning of December 21st, 1918, the Canadian Expeditionary Force for Siberia set out to begin their journey to Siberia. The first of two groups to leave Canada began their march from Willows Camp to Rithet’s Wharf, where they would board the SS Teesta and sail across the Pacific to Vladivostok. After the troops took a short seated break on Fort Street in Downtown Victoria, the trouble began.

Six French-Canadian soldiers from the 259th Battalion suddenly decided that they would go no further. When the command was given to begin marching again, the soldiers refused. One in particular stood up and shouted “On n’y vas pas a Siberia!” and refused to go any further. These soldiers– Onil Boisvert, Sylvio Gilbert, Joseph Guenard, Edmond Leroux, Edgar Lebel, Alfred Laplante, Edmond Pauze, Leonce Roy, Arthur Roy, and Adore Leroux— had all been conscripted into the force, and were furious that their time on the front had been increased beyond that of other soldiers. [3] This decision to stop and attempt to stay in Victoria rather than go to Siberia was not a wise one for these soldiers but they were firm in their conviction.[4]

Despite their desire to stay in Canada, the six soldiers were forced to the ship, being whipped the whole way by officers from their own and other battalions. On the ship, they were placed under arrest and kept in shackles for the entire trip to Siberia, after which they faced court martials. Their sentences varied, with the most severe being two years of extra duty.[5]

Conscription/Workers’ Unions

There was almost immediate backlash against the Siberian Expedition by the soldiers within the force that was amassed by the Canadian Army. The expedition was meant to be made up of men who volunteered to go, but many of those among the “volunteers” were actually men who had been conscripted and therefore had no real choice in where they were sent as part of the armed forces. While many soldiers were perfectly content to go away to another conflict when the expedition was originally announced, and even excited in some cases, as can be seen in many letters from soldiers in Europe near the end of 1918[1] because they did not know that the war would be over soon and saw the expedition as a way so spend some time home in Canada before shipping out again. However, as soon as the war ended many who had voluntarily signed up suddenly realized they no longer wanted to go away to Siberia. Because of this, the expeditionary force had to gather conscripts from wherever they could, and so soldiers who might have been able to go home due to the end of the war were suddenly forced off to Siberia. This understandably upset many of the conscripts.

Siberia was a far off, foreign, and the reasons for sending a Canadian force to fight there did not seem good enough for many soldiers. The First World War had been a matter of international concern, with thousands of people and many nations’ sovereignty being threatened, though many Canadian soldiers even grew tired of being so far from home towards the end of the conflict. Siberia, on the other hand, seemed to be a matter confined to Russia. The conflict between the White and Red Armies did not seem to concern any other powers, and soldiers were tired of conflicts in which they had no particular personal interest.

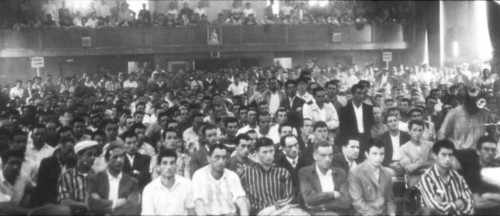

The power of workers’ unions was rising in Canada and especially in BC. The ideas of the union activists with regards to employees having a say in their working conditions appealed to the soldiers who were tired of being told what to do and having no power over their own futures. The 259th Battalion, made up of many French-Canadian soldiers, even met with some activists on the 13th of December in Victoria. In a meeting arranged by the Victoria Trades and Labour Council, which was to address the “Hands Off Russia” issue.[2] The ideas shared at that meeting prompted many of the soldiers to start thinking about taking matters into their own hands with regards to their wishes not to go away to Siberia.