Vancouver Strikes and Riots

The effects of Ginger Goodwin’s death reverberated through the province and with a spectrum of reactions. In Cumberland, Goodwin was a beloved and respected member of the community. The townspeople, though hurt and angered by the Dominion Police’s intervention and killing of Goodwin, were unable to let themselves give the deceased activist anything less than their total support. The scene of Goodwin’s death was some fifteen miles from Comox Lake, in considerably rough country. The Dominion Police in charge of the body were inclined to bury it where it was, deep in the bush. The undertaker of Cumberland, Thomas Banks, insisted on arranging a team to extract the body from the woods and bring it into Cumberland for a proper service.[1] On the second of August, 1918, the community of Cumberland joined in a funeral procession down the main street, Dunsmuir Avenue, and taken to the local cemetery for burial.[2] Nearly a kilometer of people, complete with a brass band, accompanied the body through the town.[3]

In Vancouver, the appropriate reaction was far different. Members of the Trades and Labour Council found the knowledge of Goodwin’s death suspicious, and to make a statement of workers’ solidarity, ordered a twenty four hour strike for the Trades and Labour Council and the Metal Trades Council for the second of August. This would become the first general strike in Canada, preceding the famed Winnipeg strike by a year.[4] The announcement appeared on the front page of the B.C. Federalist newspaper, stating the intention of a 24-hour strike in protest of the “shooting of Brother A. Goodwin.”[5]

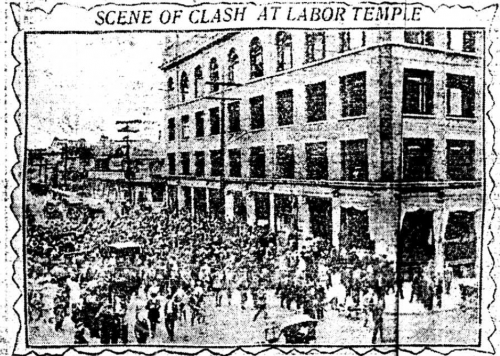

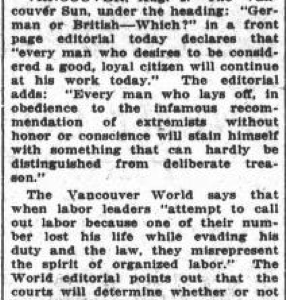

However, the political and social climate of Vancouver was not ready to accommodate such an act of working class defiance. The city was full of returned soldiers who had been present at places like Passchendale and Vimy, who were quickly insulted and angered at the knowledge of street car drivers, metal works and other unions walking off their jobs.[6] The veterans were further incensed when they learned the temporary strike was in honour of a draft evader. So they stormed the Trades and Labour Council offices in the Labour Temple, tossing records and books out windows onto the street. Worse was when these veterans attempted to throw the secretary of the council, Victor Midgeley, out a window on one of the upper floors. Fortunately, he managed to catch a ledge on the second floor and climb back in. The mob attempted the defenestration once more only to be stopped by a switchboard operator, Frances Foxcroft.[7] Failing that, the soldiers instead beat Midgeley and other members of the council out in the street, forcing them to kiss the Union Jack while belittling them with slurs.[8]

Violence and drunken anger continued on through the day and into the night.

Soldiers attempted to work the abandoned work places like the street cars and held anti-labour and anti-foreigner meetings at the Empress theatre downtown.[9] The raging soldiers were very concerned about anything socialist or Bolshevist. Also, spurned by xenophobic rage from the sight of foreigners having acquired their jobs, veterans also directed some of their hate against the eastern and southern European groups. By midnight of the third, Mayor Gale of Vancouver was able to return the street cars to operation and the strike was effectively over.[10]