Goodwin’s Life: A Road Less Traveled

Albert “Ginger” Goodwin was a labour activist whose main goal was to improve the conditions of miners in various parts of Canada. From his youth living and working in the coal fields in Yorkshire, England to Nova Scotia mines and finally to British Columbia, Goodwin was exposed to the injustices of the working class. Working conditions in the mines were extremely dangerous in the Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries, yet it seemed the only effective way to gain the attention of the company owners and improve the situation was to go on strike.

Goodwin was exposed at a very early age to how cruel working class conditions could be. His father, Walter, moved his family around the Yorkshire area from Ginger’s birth in 1887 to when he was a young man. His father was constantly trying to find a better place to ply his trade as a hewer, a position in the mines that consisted of breaking away rock and coal with human strength alone.[1] Some of these towns in northern England, in addition to having the dangers of mining, had atrocious, disease-ridden conditions for the families to live in. Denaby Main, a small mining town near Sheffield, was one of the best examples of this. Features of Denaby included smog, cramped housing and an archaic sanitation system.

Goodwin saw as a child mining strikes and how cruel the private companies that owned them could treat their workers. When the miners at Denaby went on strike in 1903, known as the Big Muck strike, the mining company simply evicted all the families in the town, causing an uproar in the press.[2] Finding his own way in the mines, Goodwin stayed in Yorkshire for only a few more years before immigrating to Canada, in 1906. Now in Nova Scotia, Goodwin joined himself with the United Mining Workers of America (UMWA), then the largest mining union in North America. Again, Goodwin lived and worked in an area with deplorable conditions in either.[3] In 1909 the UMWA was attempting recognition from the Dominion Coal Company that employed Goodwin and others in the community of New Aberdeen in Cape Breton. Dominion Coal refused to deal with the UMWA, preferring a provincial union instead, and by the spring of 1910, many of the workers, Goodwin included, were jobless and evicted from their homes. Making his way westward, Goodwin and some mining companions worked in mines near the BC and Alberta borders, and finally ending up in Cumberland, Vancouver Island.

In Cumberland, things were not all that different. By this point Goodwin was more of a social activist, both with unionization and the Socialist Party of Canada. Goodwin’s arrival was well timed. Starting in 1912 and finally concluding in 1914 was one of the largest strikes in Canadian history known as the Big Strike. Goodwin mainly supported the strike with editorial pieces in the local paper, the Western Clarion. The strike slowly petered out by 1914, which was overall a failure for the UMWA and for the workers in Vancouver Island. There was an excess of strikebreakers and unionists all after the same few jobs in the Cumberland area, which forced Goodwin to seek employment elsewhere.[4] He made his way into the interior of BC, in Trail. There, Goodwin became the candidate of the Socialist Party of Canada’s BC representative in the upcoming provincial election. Highly active in the unions in Trail, Goodwin spoke out in a forthright manner of his rejection of society’s obsession with capitalism. To Goodwin, the war was caused by greed and competition for the global markets.[5] He bravely publically opposed the war on political grounds, just as conscription was entering the Canadian sphere. The majority of Canadians did oppose it as well, given that 80-90% or so of the men conscripted sought exemption, but Goodwin stood different because his opposition was based in ideology.[6] Goodwin was exempt from conscription because of his health that consisted of rotten teeth and ulcers, conditions that would make a soldier’s life potentially fatal for him.[7] However, because of his involvement with a strike in Trail and his public denouncement of the conflict, and the pressure from Prime Minister Borden to meet the agreed quota of conscripts, the Supreme Court of Canada reversed his exempt status in January of 1918.[8]

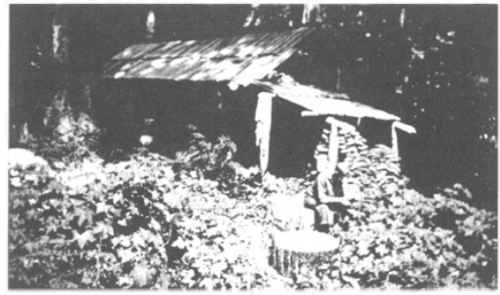

Goodwin, unwilling to submit to the government, makes his way to first Vancouver and then back to Cumberland to hide out the remainder of the war and his life. Bob Rushford, a friend of Goodwin and a distinguished veteran and now the police constable of Cumberland, is pressed by provincial government to arrest any deserters. Rushford advises Goodwin to stay low, and Goodwin, with other deserters, camp out at Comox Lake, supported with a supply of mail and food from the community of Cumberland.[9] By July, the provincial government was unsatisfied with arrests and send out the Dominion Police with special constables sworn in. One of these special constables was Dan Campbell, a former Victoria policeman, who began a widespread manhunt in the Comox valley.[10] On July 27, 1918, Goodwin was fatally shot by Dan Campbell. Campbell claimed self-defense given that Goodwin had raised his rifle at him. The death of Goodwin became a contested topic in the coming months and brought events that were unexpected, and in unexpected areas of British Columbia.

[1] Roger Stonebanks, Fighting to Dignity: The Ginger Goodwin Story, (St John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2004), 6-7.

[2] Dignity, 18.

[3] Dignity, 22.

[4] Dignity, 58.

[5] Dignity, 68.

[6] Dignity, 73.

[7] Susan Mayse, Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin, (Harbour Publishing, 1990), 120.

[8] Ginger, 137.

[9] Ginger, 147, 151.

[10] Ginger, 157.