Foundering

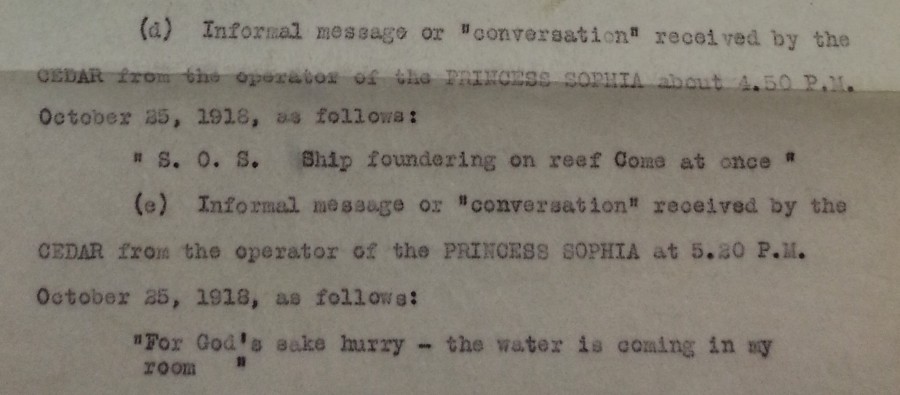

At 4:50 p.m. the Cedar received a dreaded message from David Robinson, the Sophia’s wireless operator: “S.O.S. Ship foundering on reef. Come at once.” The Cedar weighed anchor and sailed immediately. Miller, the Cedar’s wireless operator, tried desperately to re-establish contact with the Sophia after signalling to the Atlas for help, but had no luck for a half hour. Finally, at 5:20 p.m., Robinson broke through the static: “For God’s sake hurry – the water is coming in my room.” Miller told Robinson to keep calm and come back on the air only if necessary, since he knew the Sophia’s battery was draining fast. “Alright I will. You talk to me so I know you are coming.” Robinson’s message was the last anyone heard from those on board the Sophia.

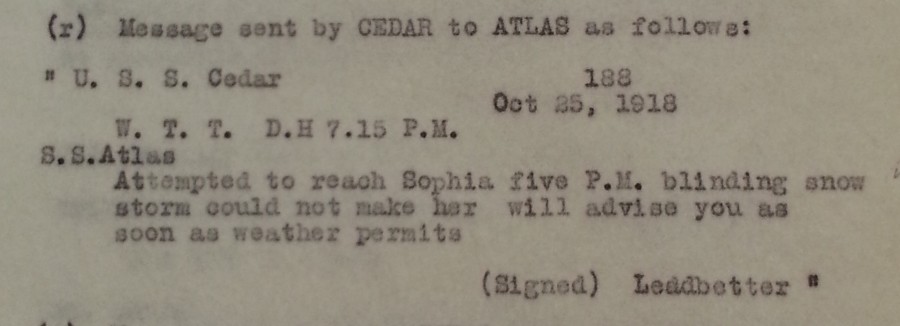

After leaving the shelter of Sentinel Island, the Cedar was caught in a ferocious winter storm. Unable to see or to hear the Sophia’s foghorn, Leadbetter attempted to reach the ship for half an hour before being forced to admit defeat and return to harbour. The storm was so fierce that he was forced to navigate on intuition more than observation, since he could not see more than twenty feet in front of him. The King and Winge guided the Cedar safely back to harbour with the ship’s whistle. After that, there was nothing either ship could do but wait for morning and a break in the storm to try and help those aboard the Sophia.

Though no one saw the Sophia sink, a timeline of the sinking has been pieced together. The high tide, combined with the wind, lifted the Sophia up slightly from her resting place of the last forty hours. The entire ship swung around 180 degrees, grinding the reef smooth under her weight. Now under the full force of the wind, the ship began to slide off the reef, ripping gaping holes in the hull until almost the entire bottom was torn out. Oil poured out of the ship, covering the ocean around the reef. The boilers exploded as sea water came rushing in to the boiler room, killing many who had taken shelter below decks and creating more holes for the ocean to rush through.

An order for general evacuation was never given, as many of the passengers were found either below decks or without life vests on. Though the crew did attempt to launch several lifeboats, they either capsized or sank immediately, as the waves were too rough for the lifeboats to handle. Many passengers abandoned the lifeboats and the ship, jumping into the stormy sea and trying to swim ashore. But the oil that covered the water clung to them, weighing down their clothes and filling their noses, mouths, and lungs with tar. Between the bitter cold of the Alaskan waters, the swirling storm, and the suffocating oil, the Sophia’s passengers were doomed.

Frank Gosse, the ship’s Second Officer and the only person who survived the immediate sinking.

Frank Gosse, the ship’s Second Officer and the only person who survived the immediate sinking.

One man did appear to survive the sinking, although rescuers did not reach him in time to save him. Frank Gosse, the ship’s second officer, seems to have made it to shore in a lifeboat that miraculously did not swamp. He was found onshore with his coat covering a head wound. Rescuers speculated he received it when climbing the rocks around the shoreline to safety. Lying down to wait for rescue, he likely died of exposure. The only passenger aboard the Sophia to survive the sinking and its aftermath was an English setter that swam eight miles from the reef to Tee Harbour, and from there traveled another four miles to Auk Bay, where it was discovered by the town’s residents two days after the ship went down.

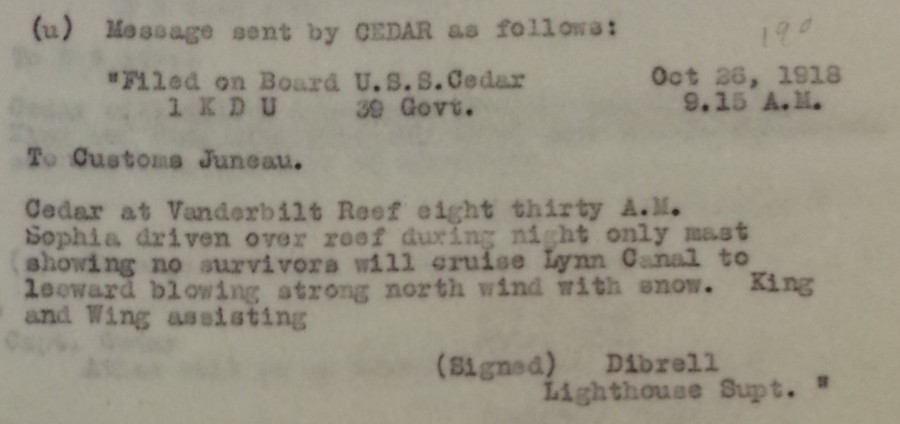

The morning of the 26th saw the Cedar rushing full speed to Vanderbilt Reef. Though it was still snowing heavily, the wind had died down enough for Leadbetter to see what he had feared: the reef was bare, and the only remnant of the Sophia was a section of her cargo mast, jutting forlornly out of the water. Leadbetter had Miller relay as much to the Atlas in a message at 9:20 that morning: “Sophia driven over reef during night only mast showing no survivors.” The sunken ship was the only evidence of the wreck. All of the oil, along with the lifeboats and bodies, had been carried away by the storm. Those aboard the Cedar, King and Winge, and the Peterson cast about for over three hours looking for bodies. None were located until 11:30 a.m., when a lookout on the King and Winge spotted a lifeboat on Shelter Island. Soon other lifeboats and bodies were found in the vicinity.

The efforts to recover all of the victims of the wreck went on for weeks, and some were never found. Those who were recovered were taken to Juneau, where the town cleaned the bodies and prepared them for travel to their originally intended destinations. The CPR’s Princess Alice, which at first had been sent to take passengers off the ship during the rescue effort, but had not arrived in time, was sent to recover the bodies. The press dubbed her the “Ship of Sorrow,” but when she steamed into Vancouver on the evening of 11 November, she was greeted with joy and revelry. The armistice had just been signed. The war was over. In deference to the Sophia tragedy, the mayor of Vancouver asked that flags throughout the city fly at half mast for one hour – between 1:00 and 2:00 p.m. – on the afternoon of 12 November. Though some did appreciate this sign of commemoration, for most the tragic sinking of the Princess Sophia was already beginning to fade into distant memory.

How did Victoria react to this tragedy? Click here to find out.

The telegrams seen on this page, along with several others, can be found at our Telegram Database.