Vanderbilt Reef

In the early hours of the morning of 24 October, the Sophia ran aground on the top of an underwater mountain known as Vanderbilt Reef. Locke had kept the Sophia steaming through Lynn Canal at full speed, comforted by the knowledge that the passage at this point was seven miles across, and that the part of the journey that was actually expected to be difficult was still ahead. Navigation of Lynn Canal in this period relied on the ship’s navigator taking a bearing from known compass headings and then attempting to stick to them as closely as possible. There was little room for error in this practice, as the slightest mistake could land a ship on the reef or even the shore. Still, it was the best bet for a safe passage. A second way that the Sophia’s crew could figure out where the ship was in relation to the shore and potential hazards was through a form of echolocation. By sounding the ship’s whistle and listening to echoes from the shore, the navigator could determine the ship’s position in the channel. These were the two techniques that Locke likely used to try and get the Sophia safely through the channel, but something went horribly wrong that morning. Either due to human error or the strength of the surrounding storm, the Sophia was pushed off course. Rather than sailing safely along the east side of Lynn Canal, she was steaming at full speed down the center, straight toward Vanderbilt Reef.

At 2:10 a.m., the Sophia’s passengers and crew were thrown across their staterooms as the ship sailed up and onto the reef, stopping almost instantly. Because of the high tides, she lifted out of the water and scraped along the top of the reef, finally settling somewhat securely into a niche. Locke immediately telegrammed for assistance, reaching the CPR office in Juneau around 3:00 a.m. The CPR ticket agent working in Juneau, Frank Lowle, was woken up by the emergency call from the harbor and rushed to the office to begin contacting ships for a rescue effort. This was a difficult task, as the Sophia was carrying far more passengers than any one ship currently near Juneau could hope to accommodate. But Lowle and his assistant soon proved themselves up to the challenge, and within hours had cobbled together a rescue team of four ships – the Estebeth, Amy, Lone Fisherman, and Peterson – that they hoped could be of assistance to the foundering ship. Because of their small size, Lowle also attempted to recruit a large fishing boat, the King and Winge, whose captain was hesitant at first to head out into the storm, but was finally swayed to sail to the rescue at 11:00 a.m.

E.P. Pond’s photograph of the Sophia’s starboard side, likely taken from onboard the Cedar.

E.P. Pond’s photograph of the Sophia’s starboard side, likely taken from onboard the Cedar.

Meanwhile, onboard the ship, the passengers and crew were comforted by the presence of the rescue boats. Auris McQueen, in a letter to his mother written the day of the sinking, mentions that the passengers were inconvenienced, but did not seem overly concerned about their predicament: “our only inconvenience is, so far, lack of water. The main steam pipe got twisted off and we were without lights last night, and have run out of soft sugar. … And as soon as this storm quits we will be taken off and make another lap to Juneau.” Despite a gaping hole in the hull, Locke determined that the ship was safe for the time being, and that it would be best to hold off on a rescue attempt until the storm died down. Over the course of the day, several ships, including those that Lowle had sent for assistance, arrived on scene but left soon after. Because of the storm, launching lifeboats in an attempt to get the passengers off the Sophia would have been suicidal. While some ships chose to try and wait out the storm so they could offer assistance if the situation changed, others determined to sail back to Juneau or to the various safe harbours along the Canal.

The high tide that rose that evening further comforted Locke and the Sophia passengers. Though the tide did shift the boat slightly, it did not cause her to slide off the reef, which would have been disastrous because of the hole in her hull, not to mention the dangers that the waves posed to the rescue ships and the Sophia’s lifeboats. Content that the ship would be able to sit out the night on the reef, Locke planned for a rescue attempt to take place during the next high tide, which was due at 5:00 a.m. the morning of the 25th. This tide was expected to raise the water level enough for lifeboats to be launched safely. One of the passengers, Jack Maskell, was not convinced. After a full day on the reef, he was beginning to fear the worst. Writing to his fiancée, he titled his letter “In danger at Sea,” and, though he tried to downplay the incident – “the boat might go to pieces, for the force of the waves are [sic] terrible, making awful noises on the side of the boat, which has quite a list to port. No one is allowed to sleep, but believe me dear Dorrie it might have been much worse.” – he nevertheless wrote out a will should the boat indeed founder: “leaving everything to you, my own true love and I want you to give £100 to my dear Mother, £100 to my dear Dad, £100 to dear wee Jack.”

Throughout that afternoon and evening, the storm swirling around the Sophia continued to worsen. Concerned for the safety of the rescue ships, Locke assured each one – via telegram or megaphone – that he believed the Sophia to be safe, and advised them to take shelter from the storm. As night fell over the reef, the Sophia’s lights flickered, then went out. A broken steam pipe caused a failure of the electrical system, leaving the passengers in the dark for their last night on the reef. The rescue ships departed for safer harbours, all prepared to rush back at a moment’s notice should the situation worsen before the planned rescue attempt the next morning.

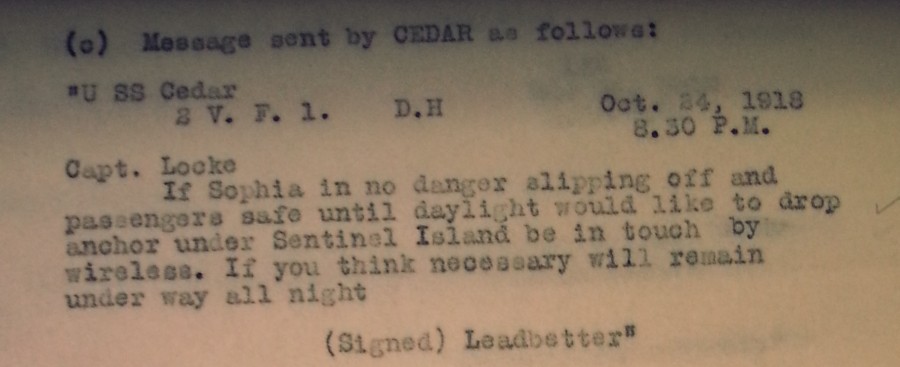

5:00 a.m. on the morning of 25 October saw the return of the larger rescue ships, the King and Winge and the steamer Cedar, which had arrived the night before. But despite Locke’s hopes for a rescue, the ships could once again only watch helplessly as the Sophia, still too high above the water, was buffeted constantly by the strengthening wind. Both ships remained nearby over the course of the day. The Cedar, captained by John Leadbetter, twice attempted to rescue passengers by setting up a breeches buoy. This required casting anchor and then stringing a line to the Sophia, which would then be used like a zip line to move passengers off the stranded ship one at a time. The attempt was unsuccessful because the Cedar’s anchor simply could not hold the ship in place in the face of the rising storm. By noon, the storm had grown severe enough that Captain Leadbetter asked Captain Locke for permission to steer the Cedar behind Sentinel Island, which would provide the ship with some shelter from the increasing wind. Locke agreed, and the radio operators of the two ships decided to break contact until 4:30 that afternoon. The King and Winge followed behind the Cedar, leaving the Sophia to brave the rising storm alone.

Click here for part three.

The telegram between Leadbetter and Locke is one of many sent over the two day period that the Sophia was stranded on Vanderbilt Reef. For a collection of the telegrams sent during this period, see our Telegram Database.